Erdogan gambles on fast recovery as Turkey burns through reserves

Be the first to know about every new Coronavirus story

At this time of year, Murat Tugay, who runs the 240-room Hotel Aqua in the Mediterranean resort of Marmaris, should be dealing with a packed guestbook and all the challenges of peak season. Instead, the hotel is closed and Mr Tugay is banking on a late summer recovery. “We still have August. We still have September,” he says.

The reality on the ground for Turkish tourism sector — and its implications for the country’s broader financial health — contrasts with the upbeat messaging from Ankara.

Speaking last month, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan hailed a sharp fall in interest rates and praised measures taken to block “malicious” attacks on the Turkish lira. Such steps, he said, were “strengthening the immune system of our economy against global turbulence.”

That could not be further from how most economists see the Turkish picture. The collapse in tourism as a result of the coronavirus pandemic has left a gaping hole in the country’s finances. Foreign investors have fled, pulling out almost $13bn from the country’s local-currency bonds and stocks over the past 12 months.

In the face of those outflows, the country has burnt through tens of billions of dollars of reserves this year in a bid to maintain an unofficial currency peg — a move that marks a rupture with a two-decade policy of allowing a free float. But, in a sign that those efforts are floundering, the lira last week lurched towards a record low against the dollar even as authorities spent billions trying to defend it.

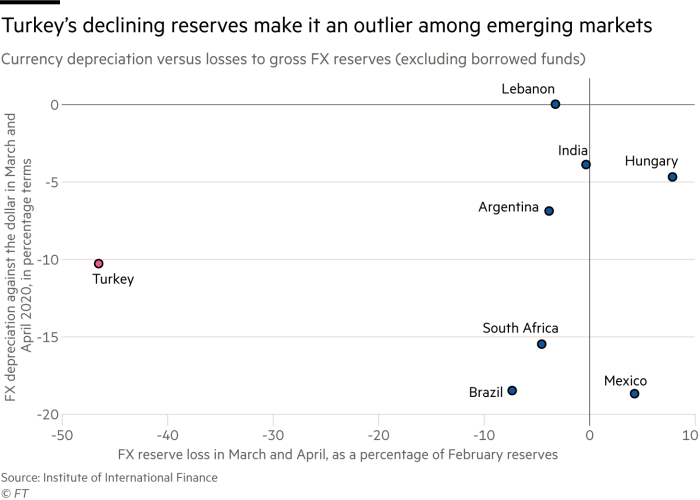

Mr Erdogan’s son-in-law, the finance minister Berat Albayrak, has said repeatedly that the nation is enjoying a “positive decoupling” from the trends seen in other emerging markets, but some analysts fear that his strategy is sowing the seeds for a currency crisis.

Robin Brooks, chief economist of the Institute of International Finance, says Turkey is a “complete outlier” but for many of the wrong reasons. It is wracking up a large current account deficit, spending billions on trying to hold its currency steady and pumping the economy with cheap credit — the same tactic that triggered a huge crisis just two years ago when the lira lost almost 30 per cent of its value against the dollar. The plunge piled pressure on Turkey’s indebted corporate sector, caused soaring inflation and led to a recession.

The risk, says Mr Brooks, is that Turkey faces another “disorderly depreciation” that would complicate the country’s efforts to recover from coronavirus. “Unless the credit push is reduced, I think the risks are building.”

Turkey’s high-risk approach appears to reflect a gamble on a fast and vigorous recovery from the pandemic both at home and in key export markets.

“If you think that the coronavirus’s impact is going to disappear relatively quickly . . . then this is an appropriate strategy,” says Phoenix Kalen, director of emerging markets at the French bank Société Générale. “It’s costly in the short term but it buys you enough time to get through this very very difficult period.”

Yet if that scenario does not play out, and revenues from tourism and other exports do not recover quickly enough, she warns that Turkey would be left highly vulnerable to future global economic shocks. “If this current situation does continue for another 12 months, it’s not sustainable,” she says. “The Turkish authorities are balancing in this fragile equilibrium, trying not to go over the cliff.”

Offsetting plan

At the Marmaris hotel, Mr Tugay is trying to remain upbeat. But, even if the hotel opens in the coming weeks, the best he is hoping for is occupancy levels of 30 to 40 per cent. The usual clientele are Britons and other Europeans aged 50-plus, many of whom have been reluctant to resume international travel as fears grow of a resurgence of coronavirus across Europe. Turkey itself, which has recorded about 230,000 cases of Covid-19 and 5,600 deaths, is dealing with around 900 new cases a day.

“For our hotel it’s all about whether our markets, whether people of a certain age, are going to be taking the risk to travel,” Mr Tugay says.

The hit to his sector is a vital part of the story of the problems that Turkey is facing. Tourism revenues are an important source of foreign currency for the country, which relies on large amounts of foreign financing to fund growth and plug its chronic trade deficit. About 45m overseas visitors helped to generate tourism income of $34.5bn last year. But arrivals were down 75 per cent in the first six months of 2020. In June, the drop was 96 per cent.

“In normal times we would be making €1,000 a day,” says the owner of a shop selling beachwear and fashion to tourists in the Turkish resort town of Lara, who asked not to be named. “Right now it’s €10 or €20.”

Ministers had hoped that the collapse in the price of energy — one of Turkey’s most expensive imports — would offset the sharp drop in tourism earnings and the plunge in other exports such as textiles, white goods and cars.

It has not played out that way. In recent months Turkey has been running a hefty current account deficit — for the first five months of the year it was almost $17bn. Forecasts for the full year figure range widely, but Barclays expects a total of $30bn — around 4 per cent of GDP.

The problems caused by the plunge in exports have been compounded by a massive credit boom that began before coronavirus swept the globe, and is now the primary tool for powering Turkey out of the pandemic.

While international forecasters expect Turkish gross domestic product will contract by 4.3 per cent this year, according to a survey by Consensus Economics, the country’s authorities insist that it will enjoy a sharp bounce back that will result in positive full-year growth.

In a bid to meet that goal, they have once again turned to credit. The central bank has slashed its benchmark interest rate by 15.75 percentage points over the past 12 months. Banks have been incentivised to embark on a vast lending spree to both businesses and consumers.

Loan growth is up 24 per cent year on year, according to Barclays — the highest level since 2013. “It’s off the charts,” says Mr Brooks. “It’s truly massive, relative to historic precedent.”

The credit push, Mr Brooks says, is "boosting domestic demand, which is boosting imports, and keeps the current account deficit wide." He adds: "In the end, the casualty to all of this is the lira.”

In such a scenario, one solution is for a country to let its currency lose value. Depreciation acts as a shock absorber and provides a natural brake on the current account deficit by making imports more costly and exports more competitive.

But, perhaps scarred by the dramatic events of 2018 — when he was just weeks into his new job as finance minister — Mr Albayrak has resisted that approach. The lira briefly hit a record low against the dollar in early May. But by imposing restrictions on foreign currency trading and selling tens of billions of dollars in the open market via the country’s state banks, authorities helped drag the lira back up then keep it almost perfectly flat for weeks before its recent wobbles.

The central bank has always denied that it is targeting a specific level for the lira. But the overwhelming majority of economists and analysts believe that it is effectively seeking to defend a currency peg.

Another way of dealing with a current account deficit is to attract foreign investment, including the trillions of dollars of “hot money” controlled by portfolio managers at global asset management firms.

But, over the past year, a slew of measures aimed at preventing “manipulation” have alarmed foreign investors — and even prompted the index provider MSCI to warn that Turkey could be relegated to “frontier market” status. Combined with negative real interest rates, these factors have driven away international capital. Foreign participation in the Turkish domestic bond market fell to a record low of just 4 per cent in mid-July — down from a 2013 peak of 28 per cent.

Costly operation

In the short term, the measures to control the lira have worked. The currency’s 15 per cent depreciation against the dollar this year means it has fared better than comparable currencies such as the South African rand and Brazilian real. The attempt to stabilise it has come at a huge cost, however. Goldman Sachs estimates that the central bank has spent $65bn on supporting the currency this year alone.

The interventions have severely depleted Turkey’s already low reserves. Gross foreign exchange reserves have fallen by $13bn so far this year to $93bn. That figure, which includes around $50bn of borrowed cash, covers just over half of the country’s foreign debt obligations that come up for renewal in the next 12 months.

To support the currency, the central bank has relied on an elaborate mechanism that borrows from the $230bn pile of foreign currency savings held by Turkish citizens in the country’s banks.

As a result, net reserves — a figure that shows how much cash the central bank has once borrowed funds and money belonging to other institutions are stripped out — are now in deeply negative territory. Net foreign assets — a yardstick for net reserves — stood at minus $41bn at the end of June, according to Goldman Sachs.

Some analysts think the system can keep going as long as Turkish savers do not trigger a run on the banks. “In theory there is no limit as long as the central bank accepts having a deeply negative position,” says one Turkish banker.

But the erosion has made many observers nervous. “We’re in a situation where there are no reserves, and the central bank is spending reserves that it has borrowed from the banks,” says Maya Senussi, a senior economist at the consultancy Oxford Economics. “The system is deficient in dollars. I’m not saying that a crisis is happening imminently. But the experience of other countries — look at Lebanon for example — has shown that deficiency becomes problematic if banks require their dollars to honour their own obligations.”

The central bank itself has always insisted that investors should look at gross rather than net figures, and insists that there are enough funds to cover the country’s foreign debt obligations.

In a press conference last week, governor Murat Uysal acknowledged that there had been some “fluctuation” in reserves but said that he expected them to recover in the second half of this year as tourism and other exports picked up. He said that the bank was working on the basis of the assumption that they would be no second wave of coronavirus.

Turkish banks and corporates have so far defied warnings that they could struggle to roll over their $170bn pile of debt that comes due in the next 12 months.

But they face a fresh spike in foreign debt repayments in October — a hump that coincides with the countdown to US presidential elections that could spark fresh market volatility. Brad Setser, a senior fellow at the Washington-based Council on Foreign Relations, says that even a small drop in the country’s refinancing rate could bring gross reserves down to “really critical levels”.

“Conceptually, there is a point when the low level of reserves themselves becomes the source of the shock,” he adds. “It starts to spook people.”

Exit path

Turkey may yet be able to find a path through the challenging period ahead without a full-blown balance of payments crisis. There has been some good news for the tourism industry in recent weeks, with the UK giving the green light for Britons to travel to Turkey. Russia, another key source of visitors, was due to resume resume flights on August 1.

Some analysts, such as rating agency Standard & Poor’s, expect Turkey’s credit boom — and the associated risks — to tail off. Others believe fears that the latest lending surge will fuel a huge current account deficit are overblown because much of the money is going towards keeping businesses and households afloat rather than fuelling demand for imported materials and goods.

More broadly, Mr Erdogan has often been lucky over the course of his 18-year stint at Turkey’s helm. A faster-than-expected global recovery from Covid-19, with a sharp rebound in trade and tourism, could help to replenish dwindling reserves before they reach critical levels.

But some analysts feel that the Turkish president and his son-in-law are pushing their luck with their unconventional economic policies. Mr Setser, who is an expert on balance of payments crises, says that Turkey is coming “about as close as it gets” to what he calls a “classic first generation emerging market financial crisis”. He adds: “I think if Turkey continues on its current path, there will come a time when the government is forced to let the exchange rate depreciate.”

Some foreign investors worry that, if there is a sharp plunge in the currency, authorities may resort to stringent capital controls — a prospect that Mr Albayrak has repeatedly ruled out.

The orthodox solution would be to hike interest rates. But Mr Erdogan — who once described high interest as “the mother and father of all evil” — may be reluctant to go down that path, as he has been in the past.

“The end game, if Turkey wants to maintain the exchange rate, has to be an adjustment in domestic policies: a reduction in credit, a higher interest rate that stabilises demand for lira and brings the current account back into balance,” Mr Setser says.

“Whether Turkey can pull that adjustment off when it runs against the preferences of the president — and at a lower level of reserves than in the past — is an open question.”

No comments:

Post a Comment