The ‘Manganese King’: a cautionary tale for China-owned foreign groups

When Jia Tianjiang, one of the richest men in north-western China, was pulled into a corruption probe in 2018, executives thousands of miles away at Jersey-based Consolidated Minerals began to panic.

Not only had Mr Jia’s company Tian Yuan just bought the minerals group, one of the world’s largest manganese miners, less than a year earlier; he also had immediately used it to guarantee a $450m loan from a state-owned Chinese bank — nearly double ConsMin’s net assets.

“There was considerable concern at the top of the company that the loan guarantee was putting Consolidated Minerals in a precarious financial position, not least because it represented nearly twice the net assets of the business,” one person close to the company said.

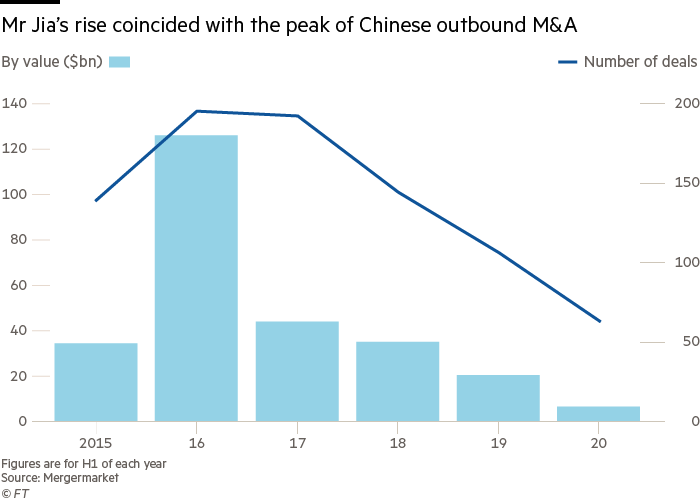

Mr Jia’s aggressive pursuit of leverage has become a cautionary tale for other companies snapped up by Chinese buyers. In recent years a handful of western groups — France’s Baccarat Crystal, the UK’s House of Fraser and Seaworld in the US — have been bought by indebted Chinese suitors only to come under pressure to be sold once again.

“In the beginning they appear to be growing at warp speed,” Violet Ho, a senior managing director at Kroll, said of Chinese groups taking on high levels of debt. “These [kinds of loans] became quite common but they have brought down a lot of Chinese companies.”

Moreover, Mr Jia’s rise from streetside apple vendor to a tycoon with ties to China’s top tier of government financiers offers a glimpse into how tight state connections have helped private businessmen amass personal wealth — and how a shift in political sentiment can wipe it out just as quickly.

He survived the 2018 probe by Chinese authorities into corruption in the financial sector, but his global business is in shambles and the collapse in the share prices of his listed companies has wiped hundreds of millions of dollars off his wealth.

Politicians and the capitalists connected to them rise and fall together, so the latter must be careful who they tie their fates to

ConsMin now risks becoming collateral damage, as failure to pay down debts could further threaten its operations, said people familiar with the matter.

“Expect to see more of this,” said an investment banker who works on cross-border Chinese M&A. “Expect to see more [foreign] companies that are in a bad position due to excessive leverage at the Chinese parent.”

Mr Jia is an unlikely finance and minerals magnate. The sixth of 13 children, he was born in 1962 in an impoverished township in western China’s Ningxia province, according to a letter written by his daughter and posted to an official Tian Yuan social media account in 2018. The letter was later deleted and was not widely reported in the press.

As a teenager he sold apples on the street, but soon found the cardboard packaging they came in was worth more than the fruit itself. He then opened a carton factory, the letter claims, although it is unclear how he bankrolled that venture.

In 2003, he got a lucky break when he used his earnings from the carton factory to buy a failed manganese mining company for cents on the dollar, turning it into an enterprise employing tens of thousands of people.

“My father would have never dreamed of becoming the richest man in Ningxia,” his daughter wrote. While he owns a private jet, she said, “he retains the qualities of a peasant in his daily life: no smoking and drinking, no gambling and no luxury spending.”

Corporate records show that in 2014 Mr Jia began doing business with Huarong, the most powerful of China’s four state-owned distressed asset managers, led by a charismatic official named Lai Xiaomin.

It is unclear how Mr Lai and Mr Jia met. But several people close to Huarong say the relationship went back years, and that Mr Jia benefited as Mr Lai transformed Huarong into a global investment bank with multiple Hong Kong-listed subsidiaries.

In 2016, Mr Jia bought a 16 per cent stake in China HKBridge, a listed investment group, and a 20 per cent stake in Huarong International, an investment banking division of the asset manager.

The next year he acquired 20 per cent of Huarong Investment and 1.1bn shares in China Citic Bank International, the unlisted international arm of a powerful state-controlled lender. He also became a cornerstone investor in Bank of Jinzhou, a lender that would require a state bailout two years later.

The same year, Mr Jia finalised the buyout of Consolidated Minerals from Ukrainian billionaire and Privat Group shareholder Gennadiy Bogolyubov.

The deal earned Mr Jia the title of “Manganese King” in Chinese media and made Tian Yuan the world’s largest producer of the steelmaking ingredient.

In 2017, Mr Jia’s investments in Hong Kong were worth more than $2bn, according to Financial Times calculations based on Hong Kong stock exchange filings. In 2018 his total wealth was estimated by research group Hurun, best known for its annual China rich list, at about $3.6bn.

Most of Tian Yuan’s major investments were linked to the state-controlled Citic conglomerate or Huarong, and each created new sources of leverage for Mr Jia.

Huarong International lent him HK$500m in 2016. In 2017 China HKBridge gave a HK$900m loan, guaranteed by Bank of Jinzhou, to Ascend Trade, a company that corporate records and statements show was controlled by the head of human resources at Tian Yuan.

But Mr Jia’s most daring use of leverage was putting up ConsMin as a guarantee for the $450m bank loan for Tian Yuan’s parent company. To get the job done he turned to the Citic conglomerate. A banking arm of the group granted the loan only a year after Mr Jia became a large shareholder in Citic International in Hong Kong.

ConsMin’s net assets were valued at just $234.5m in 2017, far short of what most international lenders would consider sufficient to guarantee a $450m loan. People with direct knowledge of the loan said such an arrangement would not be possible without close connections to state lenders.

The size and terms of the loan were never made public, but ConsMin’s 2017 annual report stated the guarantee posed no real risk to the company and that Tian Yuan had a 0.01 per cent chance of defaulting.

Less than a year later, in April 2018, Mr Lai of Huarong was detained on corruption charges in part of a multiyear crackdown on excessive leverage that entangled many of his associates, including Mr Jia.

Police would eventually find three metric tonnes of cash in one of Mr Lai’s homes, local media reported. The downfall of one of the most powerful men in China’s state finance sector sent shockwaves through the industry.

Tian Yuan and ConsMin did not respond to requests for comment on the matter.

“Politicians and the capitalists connected to them rise and fall together,” said Yuen Yuen Ang of the University of Michigan and author of China’s Gilded Age: The Paradox of Economic Boom and Vast Corruption, “so the latter must be careful who they tie their fates to”.

No comments:

Post a Comment