China’s Central Bank

Needs a Greater

Helmsman

Fickle and lacking vision and independence,

the People’s Bank of China has encouraged

risky corporate behavior and helped to make

China one of the world’s most indebted nations.

Last spring, as China struggled with the economic impact of the coronavirus, venture capital funding dried up and tech workers lost their jobs — and start-ups in the tech hub of Shenzhen went apartment-hunting. In March, residential home prices there rose at the fastest pace in three years. Entrepreneurs were taking out property-backed small business loans, which were subsidized by Beijing’s stimulus packages, to buy more property.

“What was up with that?,” you might ask.

The fact is, real estate has long held a special space in China Inc.’s heart. Of the more than 4,000 listed non-financial companies in mainland China, more than 40% hold property as investments, even though their business operations have nothing to do with the sector, according to data compiled by Bloomberg Opinion. In the U.S., for instance, less than 2% of listed companies do that.

But in China, owning these assets is essential to corporate survival. Having real estate has become the best hedge against the whipsawing policies of the People’s Bank of China, which lacks both the independence and longer-term vision of the U.S. Federal Reserve and other developed market central banks. Hostage to political considerations, the PBOC has responded to the global financial tumult of the last two decades by engineering fast and frequent credit booms followed by painful periods of tightening as regulators fretted over rising debt.

Confronted by this toxic credit cycle, Chinese companies have learned the hard way that financial security is not a given. They borrow as soon as the PBOC gets into easing mode, even if they have no imminent need for the money. Unsure when banks might reverse their leniency, companies are reluctant to make long-term productive investments. Instead, they invest their borrowed cash in risky financial products and real estate. Even by the central bank’s own admission, China’s big banks have turned into “pawn shops,” willing to lend only to large businesses with solid physical assets. When the PBOC tightens again, the only way for private enterprises to borrow is with real estate as collateral.

The central bank’s reactive tendencies have not only altered corporate behavior, inhibiting the ability of companies to plan ahead, encouraging short-term speculation and inflating asset bubbles. They have also built breeder reactors of debt like China Evergrande Group, the world’s most indebted real estate company, and helped to turn China at large into one of the world’s most indebted nations, with outstanding loans at around three times its gross domestic product.

Consider the PBOC’s behavior during this ill-starred year. Even as Covid-19 ravaged the economy, the PBOC wavered. First the bank injected too much cash into money markets and then it sucked the cash back out. The behavior of China’s government bond market is an indication of that: As developed-market bond yields dance around negative territory, China’s risk-free rate has experienced a strange, V-shaped rebound.

This seeming anomaly with the rest of the world is the unfortunate outcome of a battle waged this April with corporate interest rate arbitragers. Rather than paying salaries or shoring up working capital, large companies were taking the cheap loans made possible by the PBOC and putting their proceeds into lucrative wealth management products, the central bank observed. Much to the PBOC’s dismay, its initial easing generated more corporate debt and little real economic activity.

Starting in June, the central bank decided to do more “targeted easing,” draining money via open-market operations while beefing up programs that offer complex special lending to small businesses. Although this move stamped out the arbitrage play, it also caused China’s recent bond rout. Credit is getting tight again.

***

China has long been trying to shrink the debt pile of real estate developers. But all Beijing has achieved is an industry clever with cash management and unrepentant on leverage. Between late 2017 and 2019 — the PBOC’s latest tightening phase — developers were starting new real estate projects at a consistently faster pace than their project completions.

Cash Churn

During China's 2018 and 2019 credit tightening phases, developers were starting residential projects much faster than they were completing them

Source: Bloomberg

Developers were likely trying to speed up their cash turnover, according to Macquarie Group Ltd.’s economist Larry Hu. Seeing a long credit winter, companies wanted to cut their land bank exposure, start building and pre-sell properties as fast as possible. Then they would take their time to finish the construction phase and deliver the final product.

This financial engineering caused something of a social uproar this year. Troubled luxury villa developer Tahoe Group, the first large residential developer to default on a bond in five years, is facing pressure from hundreds of pre-sale customers who fear it might never complete projects in Beijing and Shanghai. Customers have sunk millions into deposits, but construction was halted for months. Local governments were brought in to mediate.

In mid-August, China tried something new again, proposing a “three red lines” approach to major developers. Those exceeding all three leverage metrics monitored by regulators are forbidden from borrowing more.

This rule change put China Evergrande Group into a tailspin. Together with reports that the company had written a letter to the Guangdong government warning of a potential cash crunch, it sent Evergrande’s bonds tumbling in late September. Evergrande, which has 2.3 trillion yuan ($337 billion) in assets, is a prime example of how risk-seeking and aggressive some developers have become. As of June, the company held 835.5 billion yuan in borrowings, with a whopping 47% due within a year. It had only 141 billion yuan of cash. Now China’s top policymakers are debating whether and how to intervene in the company’s travails.

***

Much of the blame for this state of affairs can be laid at the feet of China’s central bank, beginning with its lack of transparency. In most countries, companies can pick up monetary policy signals by observing central bank decisions at scheduled policy meeting dates and the run-up to them. In China, there’s no such schedule to follow. Benchmark policy rates are adjusted whenever the PBOC deems it appropriate.

In most countries, central banks strive not just for transparency, but also for the credibility that comes with consistency and discipline — qualities that the PBOC has also struggled to display. In the last two years, setting up new lending facilities and launching new benchmark rates have become the PBOC’s go-to strategies whenever it feels monetary policies are not working. Since assuming office in March 2018, Governor Yi Gang has established a new interest rate corridor to manage money markets, a new benchmark rate for bank loans, a series of targeted lending facilities to incentivize banks to lend to small businesses, and even swap programs to help banks issue perpetual bonds to shore up their capital.

In December 2018, Yi formally confirmed that the funding cost for banks — rather than the entire financial system — was what he cared about most. The key money market rate would be the seven-day repo rate for transactions that only involve banks and are backed by government and policy bank bonds; the PBOC would manage liquidity in such a way as to keep the rate within a corridor, the governor said. 1

Under this strategy, however, the funding cost for other financial institutions, such as brokers and trust companies, could shoot above the ceiling in times of distress. That happened on multiple occasions, including the year-end liquidity squeeze in 2018, in May 2019 after the central bank’s first lender takeover in decades, and most recently this January, a week before the Covid-19 lockdown in Wuhan.

Unable to withstand the complaints and pressures this policy generated, the PBOC reversed its earlier stance this year, flooding the repo market with cash, even though the funding cost for banks remained well within its interest rate corridor. For much of April and May, so much money was sitting around that financial institutions were able to lend to each other more cheaply than the PBOC’s own open-market operations. With borrowing costs so low, financial companies were happy to leverage up and offer high-yielding financial products. The interest rate arbitrage we witnessed in April was ultimately engineered, and later unwound, by the PBOC.

Where the Wild Things Are

Thanks to an ineffective interest rate corridor, the cost of money market funding in China can fluctuate beyond the levels sought by the central bank.

Source: Bloomberg

Striking a self-congratulatory note in a white paper dated Aug. 31, the PBOC said it was ahead of many global peers in establishing inter-bank “risk-free rates.” It also encouraged investors to use the seven-day repo rate as the new reference rate in setting prices of floating-rate debt and interest-rate swap products. But how many want to swap into something this volatile and unpredictable? The PBOC’s failure to stick to its interest rate corridor regime, which it formalized less than two years ago, has undermined its own policymaking.

***

Ultimately, this fickle-mindedness comes down to the central bank’s lack of independence. It is an open question in China whether “yang ma,” or Big Mama, as the central bank is dubbed, or President Xi is effectively in charge of monetary policy.

Although there is no panacea for the central bank’s woes, there are things it can do. Improving transparency, for instance, would be relatively easy: The PBOC can set up pre-scheduled quarterly briefings just as the Federal Reserve does, priming and preparing markets. Social media also helps. Just over a year ago, the central bank opened a public WeChat account to make real-time announcements, dispel rampant market rumors and publish policy papers.

Achieving consistency, though, is harder. The PBOC is not a top policy body in China’s sprawling government. Governor Yi is not even on the 25-member Politburo, which meets quarterly to set China’s leading economic agenda.

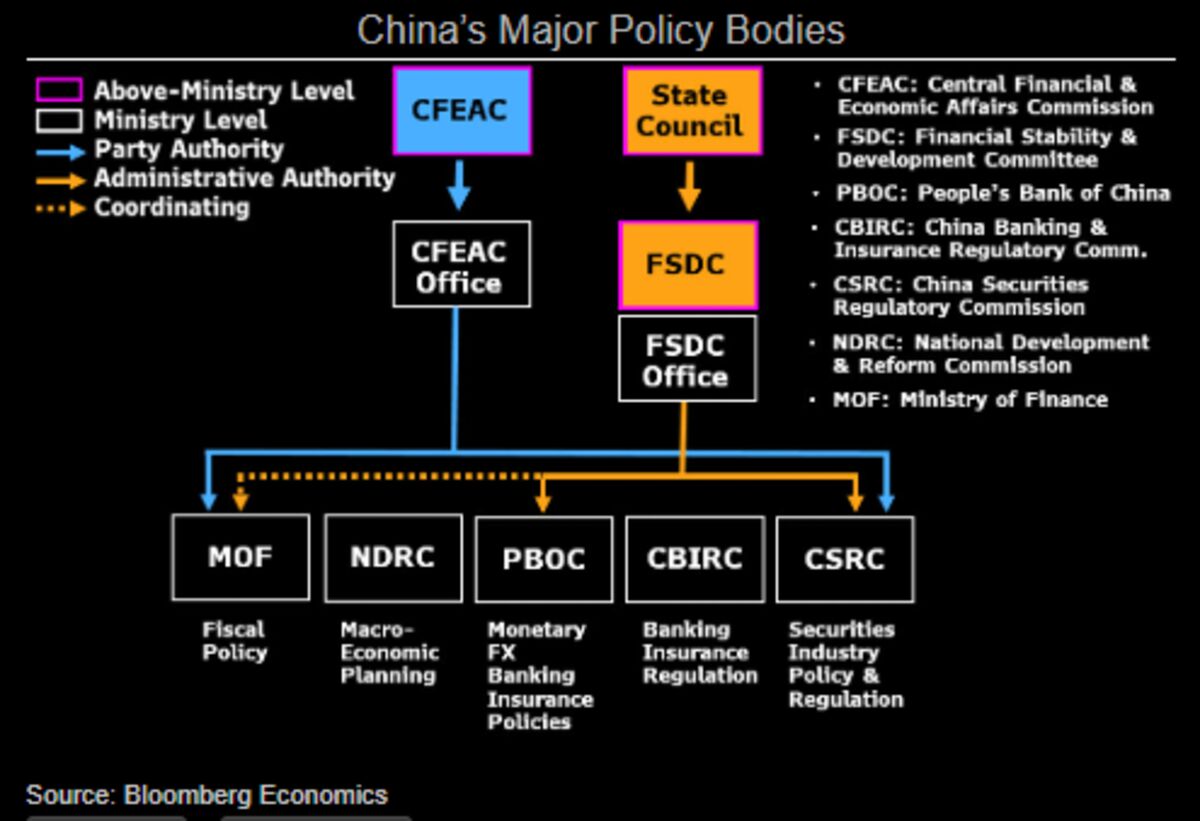

The central bank is merely on the same ministry level as China’s equivalent of the Securities & Exchange Commission. Furthermore, Governor Yi reports to too many people, as the organization chart provided by Bloomberg Economics shows.

On the administrative level, along with the Ministry of Finance, the PBOC reports to the State Council. But at the spiritual, or the Communist Party level, it also needs to please a top economic policy body headed by President Xi Jinping. U.S. financial markets may have the “Powell put,” named after Fed Chair Jerome Powell, but there can never be a so-called “Yi put.” China only has a Xi put.

Changing the PBOC’s reporting lines is a gargantuan task (and perhaps even an unrealistic one). However, one solution is to bring the sitting governor into the Politburo fold, allowing the central bank to inform top-level economic decisions with its expertise and observations. Foreigners, who are buying Chinese government bonds at record pace, look up to the governor as the top monetary authority. Sending a signal that Yi commands a key role could instill confidence at a time when China needs outside capital and is pushing market reforms.

Much as in Parenting 101, authority, consistency and good habits matter in central banking. As many a child-rearing book will tell you, if a parent vacillates, she is more likely to end up with insecure and needy offspring. In China’s top-down world, frequent credit flip-flops driven by the political needs of the moment have done just that to the real economy: Beijing’s “Big Mama” has raised a group of hoarders and arbitragers wondering what she will do next and constantly on the hunt for quick money.

No comments:

Post a Comment