African debt to China: ‘A major drain on the poorest countries’

Over the past two decades, China has emerged as the biggest bilateral lender to Africa, transferring nearly $150bn to governments and state-owned companies as it sought to secure commodity supplies and develop its global network of infrastructure projects, the Belt and Road Initiative.

But, as Zambia heads for Africa’s first sovereign default in a decade and pressure mounts on other debt-burdened countries during the coronavirus pandemic, the crisis has revealed the fragmented nature of Chinese lending as well as Beijing’s reluctance to fully align with global debt relief plans.

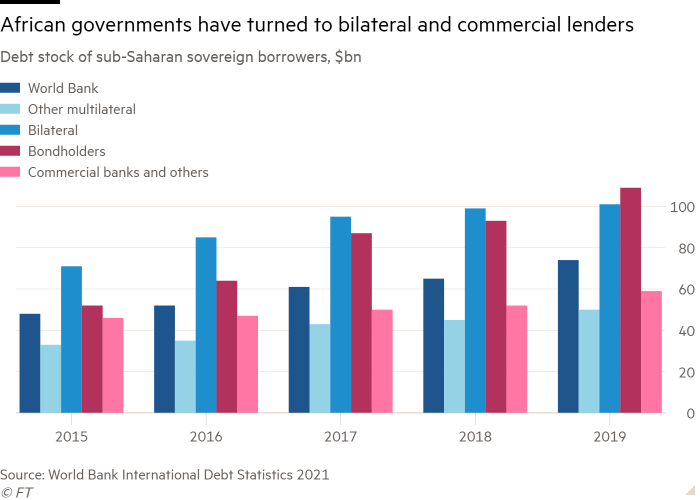

China’s share of bilateral debt owed by the world’s poorest countries to members of the G20 has risen from 45 per cent in 2015 to 63 per cent last year, according to the World Bank. For many countries in sub-Saharan Africa, China’s share of bilateral debt is larger still.

Chinese lenders have lent money to almost every country on the continent and eight have borrowed more than $5bn apiece this century. But Beijing’s involvement in a debt service suspension initiative from the G20 group of the world’s largest economies has been slow.

“It’s frustrating,” said David Malpass, president of the World Bank, this month. “Some of the biggest creditors from China are still not participating and that creates a major drain on the poorest countries . . . if you look at the [Chinese] contracts, in many cases they have high interest rates and very little transparency.”

The DSSI offers a moratorium on repayments due on bilateral loans made by the G20’s members and their policy banks to 73 of the world’s poorest countries, spreading the repayments over four years. This month, it was extended to June 2021, with repayments spread over six years.

China is so far the biggest single contributor to the DSSI, suspending at least $1.9bn in repayments due this year according to an internal G20 document seen by the Financial Times, out of roughly $5.3bn suspended by G20 members for 44 debtor countries. The next biggest contributors are France with about $810m and Japan with about $540m.

But the extent of China’s commitment is unclear. It was due to receive the largest amount this year of any G20 lender, with payments of about $13.4bn coming due from DSSI countries, according to the World Bank, while France and Japan were each due to receive about $1.1bn.

However, those figures do not include about $6.7bn of repayments that the IMF has said are under negotiation between Angola and three major creditors, which analysts believe to be China Development Bank, China Export-Import Bank and ICBC, another Chinese lender.

Angola, Africa’s second-biggest crude producer, has been the continent’s biggest borrower from China this century, receiving $43bn of the $143bn lent by China, according to the China Africa Research Initiative at Johns Hopkins University.

Sonangol, the state oil company, borrowed billions of dollars at commercial rates from the CDB, while the China ExIm Bank lent to the government at concessional rates. ExIm Bank loans are eligible for the DSSI, while Beijing counts the CDB as a commercial lender, meaning it can choose whether or not to participate. The ExIm Bank and CDB did not respond to requests for comment.

Angola’s borrowings illustrate one of the debt initiative’s major problems — China has lent to African states through a variety of organisations, meaning that information about who owes what to whom is partial and fragmented.

Ethiopia has also been one of the top borrowers, borrowing at least $13.7bn between 2002 and 2018 for everything from roads, to sugar factories, to a railway line to Djibouti. Over the past two years, China has pledged to restructure some of Ethiopia’s loans. “The Ethiopian government . . . has too many [Chinese] loans,” said a Chinese official in Ethiopia.

Chinese lending should be understood as a product of “fragmented authoritarianism”, said Deborah Brautigam, director of the China Africa Research Initiative. President Xi Jinping has committed to working with other G20 members to implement the DSSI, she noted. “That gives [Chinese lenders] a signal that they should do it, but not necessarily on the same terms.”

Chinese lenders’ domestic projects complicate matters, said Liu Ying, at Beijing’s Renmin University. “Every time China commits to relieve debt in Africa, there will be an outcry and pressure domestically from people who still say that they don't have enough to eat.”

Even as bilateral debt has risen, it still makes up only about a fifth of the debts owed by DSSI countries. Zambia has turned increasingly to China and international bond markets over less costly multilateral lenders. Its debts have quadrupled to $12bn in less than a decade, with $3bn owed to bondholders and at least that amount to China. Zambia’s bondholders question if they will be treated equally to Chinese creditors.

With the DSSI making clear the difficulty of getting all creditors working together, the G20 is preparing a “common framework” on debt restructuring. G20 officials hope this will ensure bilateral lenders share the burden equally and make relief conditional on borrowers seeking the same treatment from banks and bondholders. “It will be a proxy for China joining the Paris Club,” said one official involved in negotiations, referring to the informal group of bilateral lenders born of the debt crises of the late 20th century.

As it stands, China’s lending strategy carries risks, said Trevor Simumba, a Zambian analyst. “China has been using cheap secret loans to get access to African resources. China needs to rethink its strategy otherwise they will end up with a huge pile-up of debt that will be very difficult to restructure and even put many Chinese state enterprises at higher risk of default.”

For African countries, attracted by less onerous conditions on Chinese loans, “this crisis serves as a lesson”, said Yvonne Mhango, economist at Renaissance Capital. “To be more cautious about how much they borrow from the Chinese.”

No comments:

Post a Comment