The movement that backed Donald Trump is here to stay

The writer is a contributing editor at the Claremont Review of Books and author of ‘The Age of Entitlement’

A fortnight before the US presidential election, when some polls showed Joe Biden obliterating Donald Trump, exuberant Democrats began debating what kind of justice to mete out to the president’s followers once his movement was repudiated.

Robert Reich, labour secretary in Bill Clinton’s administration, even called for a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, of the sort established in South Africa at the end of apartheid, to “name every official, politician, executive, and media mogul whose greed and cowardice enabled this catastrophe”.

But election night brought no such repudiation. The share of Americans identifying themselves as “conservative” rose to 37 per cent while the percentage of “liberals” fell to 24 per cent. Republicans appeared to hold the Senate, and to gain in the House of Representatives.

At week’s end, Mr Trump appeared to be losing, but just barely. Whether or not he survives as a political player, the movement that backed him appears set to remain the main force in American politics.

At heart, this movement is a democratic revolt against expertise. Citizens in the west have surrendered a great deal of their decision-making power to experts — central bankers, writers of search-engine algorithms, epidemiologists. Mr Trump speaks for those who want this power back. He doubts the motives of experts. He even doubts they are experts in the first place. He thinks they’re operators, not serving the country so much as exploiting it.

Such concerns are not unique to American politics, of course. Already in the 1930s British philosopher Bertrand Russell was writing of perennial tensions between freedom and organisation, between democracy and complexity. The failure by pollsters and journalists to predict Tuesday’s nail-biter doesn’t exactly shatter Mr Trump’s credibility on the matter of expertise.

Populists are always weaker than they look, just because of who they are. They are outsiders to systems in which knowledge is turned into power. The loyalists they bring to government tend to be lacklustre and unskilled. For much of his term in office Mr Trump railed against his attorney-general Jeff Sessions for having opened the door to the investigations that handcuffed his presidency. In a political sense, Mr Trump was right — a skilled attorney-general would generally not permit investigators anywhere near his boss.

US presidential election 2020

How is the US presidential election affecting you? You tell us

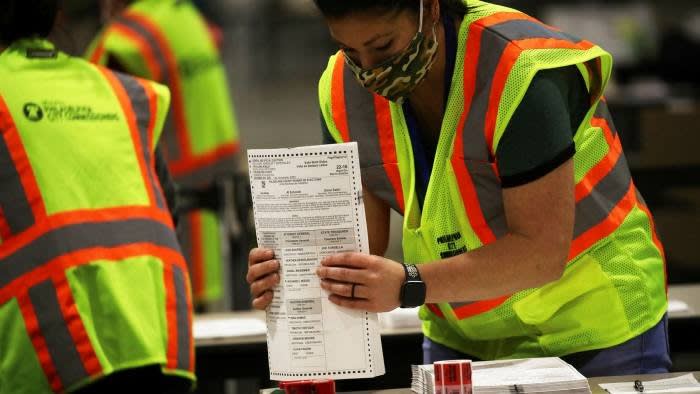

Incumbent civil servants are threatened by populism and often politicised by it. At the start of Mr Trump’s term, a judge in Hawaii invalidated his ban on travel from certain predominantly Muslim countries. In the middle of his term, Mr Trump was impeached when his own intelligence services revealed to his foes in Congress the content of secret phone calls. At the end, just days before this vote, judges in Pennsylvania altered the state’s election procedures in a way that Mr Trump and other Republicans considered conducive to fraud.

But populism is always stronger than it looks, too, and easily underestimated. Those who claimed that Mr Trump would get a better hearing for his policies if he would just stop tweeting, or making crude remarks about the “Chinese virus”, miss the point. During the Cold War, the historian Robert Conquest described socialism as a “major mind trap”: Since its premises were not actually neutral, to accept them was to risk being drawn into an entire worldview. Populists see the neutral-looking language of political correctness and human rights in the same way. For Mr Trump’s followers, his crudity is an intellectual emancipation.

But the consolidation, even expansion, of Mr Trump’s base rests on a more concrete achievement. For the first three years of his presidency, he produced steady growth (which a number of presidents have managed) in which a disproportionate share of the gains went to low-income workers (a rarer feat). Workers in the lowest quarter of incomes saw their wages rise almost 5 per cent. This was the first sustained downward redistribution of income and wealth since the last century, a vindication for voters in the forgotten parts of the country who voted for Mr Trump in 2016. It may account for the shock of this election: the gravitation of young Latinos and black men to Mr Trump’s candidacy.

Mr Trump has changed the way Americans in both parties think about their dependence on cheap Chinese goods. Trade sceptic Robert Lighthizer, the US Trade Representative, has been a capable appointee. When a supposedly advanced industrial country proves initially unable to manufacture surgical masks, hand wipes and ibuprofen in a pandemic, it has taken globalisation too far. Even Mr Biden made “Buy American” a pillar of his campaign rhetoric.

The long-term prognosis for populists is seldom good, because populism sets itself against those businesses and government leaders working to bring technological and social progress. But as long as those leaders are heedless and selfish, populism will have its day.

Clearly its day is not yet done. “We are a working class party now,” tweeted Missouri senator Josh Hawley on election night. “That’s the future.” Whatever happens to Mr Trump, the Republican party has been rebuilt around the electorate he brought it.

No comments:

Post a Comment