‘Foreign agent’: Putin’s new crackdown on the opposition

Ksenia Fadeeva was born and raised in Tomsk, the Russian city in the heart of Siberia. She attended local schools and the city’s state university. And in September, aged just 28, she was elected to the city council, defeating the candidate of Vladimir Putin’s ruling party.

Yet the next time that Ms Fadeeva runs for election, her name on the ballot will most probably come with an official warning for voters that she is a “foreign agent” — if indeed she is permitted to run at all.

That is just one upshot of a series of bills rushed to Russia’s parliament in November, following the unexpected success of Ms Fadeeva and other anti-Kremlin candidates in September’s local elections, which are set to further tighten Russia’s already repressive electoral laws in a bid to stifle rising dissent at the ballot box.

While Mr Putin’s regime is generally popular, propped up by powerful security services, huge state control over the economy and a largely obsequious media, it remains hypersensitive over potential threats and paranoid about instability and is rushing to smother any elements of independence in the tightly controlled political system.

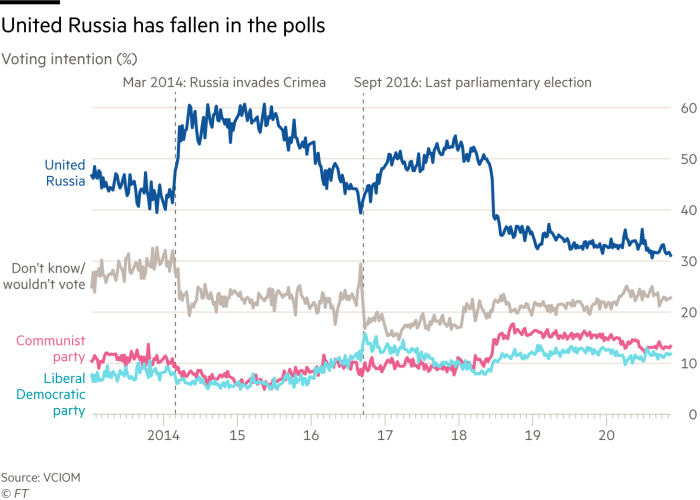

Mr Putin’s trust ratings have fallen this year, while support for his United Russia party has sunk to a record low, battered by years of falling real incomes, a pandemic-induced recession and a turgid economy that has been given little support from austere government spending.

As a result, at next year’s parliamentary election the party will probably struggle to retain its current hold on more than three quarters of the chamber’s seats, a supermajority that gives the Kremlin an iron-like grip on lawmaking and leaves no room for political debate.

That threat has sparked a rash of legislative proposals designed to hamper opposition parties before the current convocation of MPs loyal to Mr Putin step down and begin campaigning.

Four separate bills were tabled on three consecutive days in November, outlawing the last remaining legal means of spontaneous protest and increasing the state’s control over content shared online.

In the case of Ms Fadeeva and thousands of other Russian activists, campaigners and potential candidates, the new bills make use of the country’s infamous “foreign agent” designation, broadening the scope and impact of a term first written into law in 2012 and which has been steadily expanded since to target those whom the Kremlin deems enemies.

Top of that list ahead of critical elections slated for September is Alexei Navalny, the anti-corruption campaigner and opposition politician, and his organisation’s “smart voting” initiative, which directs disgruntled voters to support candidates most likely to defeat the United Russia nominee — and helped Ms Fadeeva and her colleagues overturn the party’s majority in Tomsk.

“I am certain that all these repressive bills are a response to our victories . . . to the success of smart voting,” says Ms Fadeeva, who heads Mr Navalny’s regional office in the city. “They are terrified of what to do given the crashing ratings of United Russia and Putin and are trying to tighten the screws.

“United Russia understands perfectly well that they will not be able to win the elections to the State Duma honestly,” she says. “Therefore, now we see the emergence of these crazy new laws. They tried to stop us with endless arrests for rallies, fines, searches, and criminal cases. It didn’t work . . . It is clear that they will continue to come up with more and more repressive measures in order to somehow stop us.”

A growing witch hunt

A term loaded with hints of subversion and espionage, “foreign agent” was first used to stigmatise Russian NGOs which raised money overseas, casting them as traitors or implying that they acted on behalf of an overseas government to undermine the state.

Broadened last year to include foreign-backed media groups, it also burdens the designated entity with scores of bureaucratic requirements such as quarterly reports on political activities and financing, threatens them with impromptu raids on their offices, and imposes heavy fines for adjudged non-compliance.

The proposed law, tabled on November 18, further weaponises the existing legislation by expanding the term to cover an individual deemed to have received any material or organisational support from overseas, or anyone affiliated with or supported by a Russian entity already designated under the law — such as Mr Navalny’s organisation.

Those individuals would then be banned from holding municipal government positions, and when running as election candidates would be labelled as a “foreign agent” on ballots, campaign literature and in media reports.

“Certainly, it is a label which scares people off,” says Ekaterina Schulmann, associate fellow in the Russia and Eurasia Programme at Chatham House. “It has significant negative connotations. And it will also scare candidates from being associated in any way from support of the smart-voting initiative.”

Opposition figures will probably be blocked from running in the election using existing laws on how candidates qualify and regulations preventing, for example, convicted criminals from being on ballots, says Ms Schulmann, adding that the new laws were about “fine-tuning” the pro-government system.

“There is an evident attempt to brand smart voting as a foreign-supported activity,” she says. “This all points pretty straightforwardly to seeking to hamper candidates supported by Navalny and his regional network.”

Andrei Klimov, head of the commission for the protection of state sovereignty and prevention of interference in the internal affairs of the Russian Federation in the country’s upper house of parliament, has defended the measures as “balanced and seriously formulated”.

“Our commission has a lot of materials relating to how foreign states, organisations and individuals are trying to engage in political missionary work in Russia,” he told the parliamentary journal last week.

“They do not hide that the ultimate goal . . . is to change the political system of the Russian Federation.”

Critics argue that the phrasing of the law is so intentionally broad that it could easily be used by the government to smear opposition politicians who have never received any direct overseas funding, but may have attended an event organised or sponsored by a foreign group or been promoted by a foreign-backed media outlet, for example.

“The bill signals a new witch hunt of civil society groups and human rights defenders standing up for justice and Dignity,” says Natalia Prilutskaya of Amnesty International’s Russia office. “The Russian authorities have already starved civil society financially and forced many organisations to close. Now, they are further demonising individual activists.”

Stifling civil society

Russia’s political opposition has long been forced to navigate an ever-growing list of obstacles in its bid to challenge Mr Putin’s almost 21-year-long regime, from burdensome legal requirements designed to trip them up to frequent harassment from state and quasi-state entities.

Sometimes the attacks are physical: Mr Navalny, who has been barred from running against Mr Putin due to a previous fraud conviction that the European Court of Justice has ruled was politically motivated, was poisoned with the banned military-grade nerve agent novichok in August, while campaigning in Tomsk in support of the smart-voting initiative.

He has accused the Russian state of being behind the assassination attempt, which left him in a coma for 18 days. He is still recuperating in Berlin, where he was treated. The Kremlin has denied any involvement in the poisoning.

Prior to the attempt on his life, Mr Navalny had been repeatedly jailed, preemptively arrested to prevent him from taking part in protest marches, and attacked with a chemical that left him partially blind in one eye.

The offices of his Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK), which regularly publishes investigations into alleged graft by state officials and prominent Russian businessmen, have been repeatedly raided by security services.

But it is Russia’s courts and laws that inflict the broadest damage. FBK, which was branded a “foreign agent” in October last year, is now in liquidation, after a defamation lawsuit brought by Yevgeny Prigozhin, a businessman whose connections to the Kremlin have earned him the nickname “Putin’s Chef” as well as US sanctions, left the organisation with a Rbs29m fine.

According to Ms Schulmann, the slew of proposed new laws targeting opposition politicians suggests that the approach to next year’s elections could be similar to the Moscow city elections in 2019, where a decision not to include almost all opposition candidates on the ballot sparked the largest popular protests in the capital for almost a decade.

In that vote, which was the first to be targeted by Mr Navalny ’s smart-voting initiative, United Russia lost a third of its seats on the city council and saw its majority cut to just five. In the local elections this September, in addition to the wins in Tomsk, smart voting also helped end United Russia’s majority in the council of Novosibirsk, Russia’s third-largest city.

Adding to the Kremlin’s concerns ahead of the parliamentary ballot next year are ongoing protests in Khabarovsk, a city in Russia’s far east, against the arrest and replacement of a popular local governor, which have taken place daily for the past four-and-a-half months.

At the same time, this autumn Mr Putin watched in concern as popular protests against rigged elections toppled the president of one post-Soviet neighbour — Kyrgyzstan — and pitched another, Belarus, into crisis.

The proposed laws are United Russia’s response to those threats, civil rights groups say. Tanya Lokshina, associate director for Europe and Central Asia at Human Rights Watch, says the legislation would impose “new draconian restrictions on independent civic activity”.

“It will enable the government to designate individuals as foreign agents, obligating them to present themselves as such when making public comments and basically barring them from participation in elections, including local ones,” she says. “The government clearly aims to stifle civil society.”

Moscow has long claimed that foreign countries, and particularly the US, have funded Russian organisations and individuals seeking to destabilise the country, topple Mr Putin and provoke a “colour revolution” aimed at installing a pro-western administration. Russian MPs have pointed to US rules mandating the registration of lobbyists for foreign countries as synonymous with the proposed legislation.

In addition to the bills regarding foreign agent status, Russia’s parliament is also discussing legislation to curb freedom of protest and internet content.

The first would give Moscow the right to restrict access to YouTube, Facebook and Twitter, social networking sites that are heavily used by opposition politicians to publish campaign materials and recruit typically younger supporters as a means to work around a Kremlin-mandated boycott by the country’s main television channels.

The second would close the last remaining loophole for unsanctioned street protests. Currently, administrative approval is required for public rallies. As a way around that, citizens have staged single-person pickets, where one protester holds a placard for a few minutes before passing it to a second person waiting in line. The new law, tabled in parliament by a United Russia MP, would outlaw this practice.

“Nowadays nothing should be surprising, especially when it comes to the current trends in Russian lawmaking. Nevertheless, this has turned out to be so shocking in terms of issuing prohibitive initiatives from atop the mountain that it is impossible to feel unmoved in response,” wrote Dmitri Drize, deputy editor of Kommersant, in an opinion piece for the newspaper, one of the country’s most-read broadsheets.

“On the one hand, everything is possible [in Russia], but on the other, only in theory,” he said of the impact of the proposed legislation. “If you are going to become an independent politician, or if you decide to protest against something, you will understand that it is impossible to do this legally.”

It’s all about the economy

At the last parliamentary election in 2016, opposition parties made little impact. United Russia romped home with 54 per cent of the vote, winning 343 seats in the 450-seat chamber.

But much has changed since then. At the time Mr Putin and his party were riding high on a wave of popular support for the Kremlin’s invasion and annexation of Crimea two years earlier.

Today, United Russia’s support stands at just 31 per cent, according to state-run pollster VCIOM, after hitting a record low of 30.5 per cent in August.

Most disgruntled voters cite the gloomy economy. Even before the coronavirus pandemic, the economy had been moribund since 2014, when western sanctions imposed over the Crimea annexation combined with a plunge in the price of crude oil — Russia’s key export — to pitch the country into a sharp recession. Real incomes have fallen for five of the past seven years.

This year, GDP is expected to fall by 6 per cent, according to the World Bank, as Moscow struggles to tackle the spread of Covid-19 with sporadic lockdowns and scattershot quarantine measures.

Even as Russian incomes dropped 8 per cent in the second quarter of this year, the largest fall for more than 20 years, the government refused to increase financial stimulus, which has been much smaller than other major European nations.

According to a survey conducted in October by the Levada Center, Russia’s sole pollster independent of the government, 43 per cent of citizens said they thought the country was heading in the wrong direction, up from 23 per cent in 2014.

“Each of these new bills makes sense only in the context of elections, of course . . . [United Russia] got scared,” says Leonid Volkov, head of Mr Navalny's regional network. “This is nothing new: just their usual contempt for the citizens of Russia.”

Mr Klimov says he expects the laws to be passed before the end of the year, to make sure they are active before September. “This is extremely important — we are striving to implement a set of planned legal response measures before the start of the election campaign in 2021,” he says. “This is no coincidence.”

While only winning a simple majority would not be a grievous blow to United Russia, a worse result that forced the party into coalition government with other broadly pro-Kremlin but at times unpredictable parties like the Communists or nationalist Liberal Democratic party would significantly disrupt the Kremlin’s control of lawmaking.

It would also complicate any potential succession manoeuvres should Mr Putin decide to step down in 2024. His fourth term as president will end that year but constitutional changes pushed through parliament this year allow him to run for two more six-year terms.

“This quite frantic legislative action does show the nervousness in the minds of the [ruling party] candidates,” says Ms Schulmann, who last year was dismissed as a member of Mr Putin’s Presidential Council for Civil Society and Human Rights alongside three other outspoken officials who had criticised the government’s handling of the Moscow protests.

She adds: “The direction and intention of these repressive political policies show what the perceived threats are to that goal: bad foreigners, foreign influence and possible mass protests and rallies, and YouTube . . . the alternative television that threatens the state TV channels’ monopoly.”

With less than 10 months to go before the election, Ms Fadeeva — who says all her fundraising comes from local sources — says she is unbowed by the legislative onslaught, if a little insulted.

“Certainly, being labelled as a ‘foreign agent’ is unpleasant and even offensive to me,” she says. “Yes, perhaps some parts of the electorate may be put off by this . . . but the main thing is to convince our supporters to attend the elections.

“Thus, we must keep working as we have always been doing” she adds.

No comments:

Post a Comment