The free-market gamble: has Covid broken UK universities?

The pandemic has exposed the impact of 20 years of turning higher education into a marketplace and students into increasingly dissatisfied customers

Last modified on Sun 17 Jan 2021 08.21 GMT

In 2018-19 Manchester City FC had revenues of £535.2m. Manchester United had £627m. The University of Manchester made more than £1bn – not far short, in other words, of the combined income of the city’s two global sporting brands. This is in many ways a cause for celebration, a sign of the economic power of higher education, of British success in attracting foreign students and the high fees that they pay, of the contribution that universities can make to the prosperity of their host cities.

But, for a billion-pound business, you might have expected better than their handling of the pandemic. Last summer, as students tried to decide whether to stay at home or go to the campus for the first term of the academic year, they were told they would receive “blended learning”, a combination of online and in-person teaching. They were offered the “hope” as one student says, “that everything would be as normal as possible”. They didn’t need much encouragement, especially all those first-years for whom arrival at university was the pinnacle and goal of their education to date, and they went.

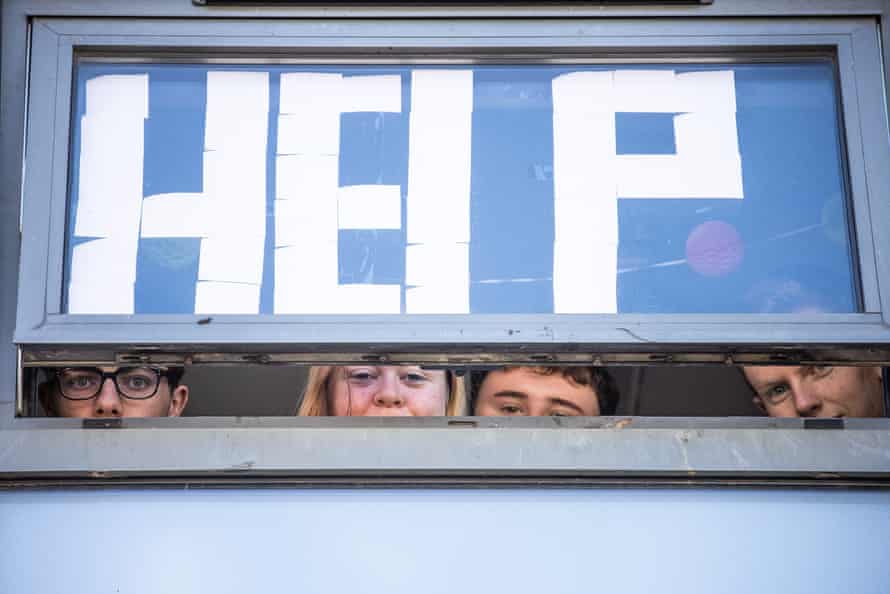

It rapidly became clear that they would receive a freshers’ experience like no other. There would be little or no in-person teaching. As the second wave of Covid-19 took off, and as Manchester became one of the worst-affected areas, they were ordered to stay in their halls of residence, confined to apartments with people they had never met before, with all the stresses that go with living away from home for the first time. Some got on well with their newfound cellmates, some didn’t. They passed their time as best they could, watching Bake Off, “doing generic stuff,” as one puts it, “that you do when you’re hanging around”.

Gyms, which are among the attractive facilities with which universities market themselves to potential students, were closed. Green space was fenced off. “We were given some concrete,” I was told, “shared by about 50 students.” Comparisons with prison yards are hard to avoid. Given that students weren’t meant to go to the shops, the university arranged for food to be delivered, but some of it was “out of date” and “arrived the day before we left isolation”. Covid-19 spread rapidly among the locked-in residents.

Early on the morning of 5 November a metal fence was erected without warning around halls of residence in the Fallowfield Campus, with private security monitoring a single entrance and exit. The university said this was to prevent entry by non-residents, but by the end of the evening they apologised, while angry students tore the fences down. In a separate incident a black student at Fallowfield was held up against a wall by security guards and told that he looked like a drug dealer.

Now, with the latest lockdown, students have been asked not to return. For many, though, it is impossible to work away from the university, not least because they left their books and belongings in their rooms before the Christmas holidays, when the government’s messages about future restrictions were still ambiguous.

Unsurprisingly, students are protesting. Rent strikes have been organised, which have succeeded in getting a reduction on the first term’s rent, and Student Action for a Fair and Educated Response (Safer) has been set up to campaign for fee reductions. A striking part of their argument is the way they frame their case: we are consumers, you are a business, you are selling us a product. We therefore demand, as consumers do, money back and compensation for unsatisfactory service. “If you’re selling a commodity, we have consumers’ rights,” says Cathy Wippell, a third-year student at Manchester and a founder of Safer. “It should,” she says, “have been very apparent they were promising something they couldn’t deliver.”

These issues are not unique to the University of Manchester. Similar problems arose in the city’s other big university, Manchester Metropolitan. Orla Katz Webb-Lamb, a second-year politics and languages student at the University of Sheffield, has invited students around the country to comment on their experiences via an online survey. “Like eating glass and staring into the abyss,” is one of the 300-plus responses she has so far received. “Being a student in a pandemic is like screaming endlessly in an empty room” is another. “We were lied to,” says another, “and then expected to produce the same quality of work while also paying the same amount of money for sub-standard experience. Especially when we pay rent for accommodation we were specifically told not to live in.”

Many are reacting to a fundamental shift in the provision of higher education in England over the past two decades, in particular since the coalition government’s reforms from 2010 onwards. Universities now have to act, to a much greater degree than before, like businesses, competing to attract the highest number of students and the income that comes with them, as well as maximising their revenue from other sources and reducing their costs. They market and advertise and pay high salaries to senior executives. In principle they can merge and acquire, and they can go bust. These changes are called “marketisation” and “commodification”, especially by those who oppose them.

“The crisis is to do with the commodification of education,” says Wippell. “If it had been free” – if fees had been fully paid by government as in the past – “we wouldn’t have been asked to go back to university.” “A lot of students have realised that we really are being exploited for profit,” says Finley Gore, a first-year who is helping to organise a rent strike. The university’s business model depends on income from fees and rent, they argue, so they didn’t want students to stay away and defer their courses. The resulting “Covid bath”, says Wippell, wasn’t only a danger to students: “students’ families were put at risk, and the people of Manchester. If money hadn’t been a factor that wouldn’t have happened.”

Like most universities, Manchester relies on income from overseas students, so crucial that eventually they chartered planes to fly them in, for whom a campus deserted of their British counterparts would have been an off-putting prospect. Conceivably Manchester’s ambitious building programme, which includes for example the Alliance Manchester Business School with attached 19-storey hotel, reduced their ability to absorb the shock of the virus. There’s no doubt that their decisions were made in the context of a colossal financial challenge. And British universities, however large and venerable they might be, are not immune from bankruptcy.

The point here is not to demonise Manchester or any other university. Universities UK, the collective voice of 140 universities in the United Kingdom, says that universities have invested “very significantly in online support, equipment for those who need it, as well as providing support for isolating students, looking at online and in-person activities to beat loneliness and creative thinking to support students and help them progress.” But they have been put in an almost impossible position by a government that has promoted entrepreneurial expansion but has yet to show them the sort of crisis support it tried to extend, for example, to the hospitality industry.

The coalition’s most remembered change in higher education was to increase the cap on tuition fees in England to £9,000 a year from £3,000, a figure that is now £9,250. Tens of thousands marched in protest. The Liberal Democrat part of the coalition, which under Nick Clegg had wooed student votes with their promise to abolish fees altogether, dealt itself an electoral blow from which the party has never recovered. But David Cameron’s government also made a profound change to the way universities receive funding: whereas previously most came from government funding councils, it would now come attached to each student they admitted. More students meant more money.

In 2015 the chancellor, George Osborne, removed a cap on student numbers that had been imposed until then. From now on the number of students that a university could recruit would be without limit. Universities have always been competitive with each other, but they would now have to vie as never before for the favours of school-leavers. A market would be created in higher education. David Willetts, the universities minister behind the reforms, says that, thanks to these changes, “more students in England now get their first choice, and I’m proud of it.”

The £9,000 fee was intended as a maximum, to be charged in “exceptional circumstances”, as the government put it at the time. It was expected that leaner, hungrier institutions would offer lower fees in order to compete on price. In the event £9,000 turned out to be the almost universal standard rate, the minimum as well as the maximum, as few wanted to be the outfit selling cut-price and therefore suspect degrees. It was also hoped that new colleges would spring up, incentivised to disrupt the closed shops of existing universities. AC Grayling’s New College of the Humanities, funded by private equity, was one product of the new policy. Others, in what was an under-noticed scandal, were unmonitored private colleges where underqualified students were handed public money to take courses of almost no meaningful value.

Competition, since most were charging at the same rate, had to take other forms: marketing, advertising in Premier League football grounds and on public transport, investment in shiny new buildings that would – as well as serving their stated purposes – look good in brochures. Vision statements would proclaim excellence, innovation and diversity. Universities would strive to look good in the league tables and in government-led metrics and surveys. All to win the hearts and minds of 17-year-olds trying to choose between hundreds of options, who were unlikely to command all the facts needed to make fully informed choices.

Universities also strove to maximise their revenue from other sources, such as renting out facilities and accommodation for conferences between terms, and (especially) foreign students who pay higher fees than those from Britain. Those new buildings had to serve these markets, too. They had to meet the requirements of commercial conference-organisers and grab the attention, in a crowded marketplace, of far-away potential students. Some are magnificent and award-winning; many are in the sleek modernist style of high-end office buildings, anticipating the settings in which students might spend the rest of their working lives.

There was a boom in building student housing, both by the private sector and by universities, towers of tiny rooms, often clad in gaudy colours – whether to ingratiate themselves with youth or to disguise their cheapness – that have become as ubiquitous a feature of the British urban landscape as gothic revival churches and retail sheds. There are several attractions for property developers in building student accommodation – for example the planning system does not oblige them to contribute to affordable housing, as they do with other types of development – as a result of which the education-themed real estate sector, according to the Financial Times, provides accommodation for about 600,000 people and is now worth an estimated £50bn. For universities rent from halls of residence is another income stream. Among the complaints from Fallowfield students is the level of rent – high in comparison with private lettings in the area, they say.

If universities were to be entrepreneurial businesses they would borrow accordingly, and the sector’s debt trebled in a decade, to £12bn in 2018. Raising private finance, according to one critic of the system, “generates imperatives for market-conforming behaviour” – maintaining their credit ratings, committing to a continuous flow of students and their fees. New breeds of consultants have grown up, “a coterie of corporate experts” as Amelia Horgan of the University of Essex puts it, to help universities maximise their intakes, sell themselves and raise their ratings.

The same imperatives require costs to be suppressed, including such things as the pensions of academic staff, attempts to change which led to a series of strikes from 2018 to 2020. Academic employment was long based on the principle that, while you would never get rich, you would at least be secure. With the erosion of pensions and long-term contracts, say academics and their union representatives, the second half of this bargain is being taken away.

And beyond the battles over budgets and contracts there is a culture shock, the belief that a university’s spirit of open inquiry cannot be subjected to the mechanisms of corporations.

“We’re in a condition of managerialist realism, beyond which we can’t think,” says Michael Hrebeniak, director of studies in English at Wolfson College, Cambridge. “An obsession with the business discourse of procedure, training and skills has eroded the trust in freewheeling encounter that is crucial to the life of the mind.” A professor of architecture says: “We have to sit through lectures of flow diagrams on how the new structure works. It’s like tractor production quotas in the USSR.” Academics complain of the disappearance of trust, which they say was fundamental to the way they worked, and its replacement by measurement and monitoring.

Critics of the current arrangements often look back to the time before loans and fees, in the 70s and 80s, when the state paid both your fees and a maintenance grant. “I came from a background where people did not go to university,” the architecture professor tells me, “and it did far more than provide me with my career. It enriched my life.” Now, he says, “with the debt that students end up in, the question ‘will I get a job?’ becomes the frame through which education is looked at. It makes them much less likely to take the kind of risks that are experimental in terms of finding new knowledge.”

To most of these points Willetts has answers. In 1980, he says, far fewer young people went to university than today (the figures are about 15% then compared with 50% now). He argues that it is therefore not feasible to fund each of these students with public money at the same levels as 40 years ago. By effectively taxing the future careers of students, loans have reversed what had been a decline in the amount of funding per student reaching universities. He and his colleagues designed the loans to be “income-contingent”, which means you don’t have to pay them back unless you earn enough to do so. Fears that low-income students would be deterred have been unfounded, he says: “We have record highs of applications and more students from poor backgrounds.”

“I’m not going to defend every bit of crass management,” he says, of complaints about corporate culture, but if a potential student “is sitting in a prosperous Indian suburb, a university needs to have a fantastic website, and a marketing pitch. The idea that you can attract them without modern marketing is unrealistic.”

He also argues that the landscape of competing institutions is a reflection of a British tradition, long pre-dating the coalition reforms, where universities are autonomous entities, where students have a nationwide choice where to go, but where they have no guarantee of admission anywhere. In other European countries it is more usual for school-leavers who have passed the right exams to go as of right to local state-run universities. “We don’t realise how unusual the British system is,” says Willetts. “People who complain are deeply unhistorical.”

But there remains a deep flaw in the idea that you can have a free market in higher education, which is that a degree course is not like a can of baked beans, where you can try out different brands to find which one you like. “Most people have one go at higher education,” says Andrew McGettigan, author of The Great University Gamble: Money, Markets and the Future of Higher Education. “And the benefits are not apparent for years.” So a 17-year-old, faced with a choice of more than 400 providers, has to rely on what McGettigan calls “proxy sets of data trying to capture quality”.

This means league tables and metrics such as employment prospects after graduation, and official assessments and surveys. One of these is the National Student Survey, which performs the ostensibly valuable task of asking students what they think of their courses, but is a bete noire of many academics. Their complaint is partly about the imposition of yet more bureaucratic procedure on their and their students’ time – “we have to badger our students to get them to bloody well do it,” says the architecture professor. “We have an event with free pizza, chips and beer to get them to fill in the forms.” Metrics, he also says, are “a very poor way of describing what is really going on”.

They can also be gamed. One of the most significant factors in students’ happiness is the grades they get in their exams, which incentivises universities to mark them higher, which contributes to a grade inflation that has seen first-class degrees rise from 16% of the total in 2010-11 to 30% in 2018-19, while the proportion of those gaining either a first or a 2:1 has climbed from 67% to 79%. Several academics tell stories of receiving very strong hints from management that they should raise the marks they award.

This is clearly bad for the credibility of higher education and for the recognition of genuine achievement, and is ultimately self-defeating. The gaming of metrics also favours those institutions with the business nous and the resources to do it better than others, which tends to mean those that are already larger and more successful. Which contributes to another deficiency of the imperfect market in higher education – that it favours not necessarily those offering the best and most valuable courses, but those best equipped to operate the strange machinery of incentives and opportunities.

In practice the 24 universities of the Russell Group, which was set up in 1994 to promote the interests of leading institutions, have done well. Their brand, clout and organisation are just what is needed to thrive in the modern academic world. Some outside have struggled. McGettigan describes one highly respected institution which, caught flat-footed by Osborne’s removal of the numbers cap, lost out in the annual race for admissions. It had to accept less-qualified students than usual, which meant more resources had to be put into teaching and foundation courses, moving the focus of the institution away from research.

Willetts’s dream, as professed in his book A University Education, is of diversity and choice, of nimble challengers to the established order. “Universities come in many shapes and sizes,” he wrote. Some courses, he argues, should be vocational and closely allied to future employers, as some former polytechnics have successfully achieved. Others should not. But the current climate, which the coalition government did so much to create, tends to favour both established players and corporate uniformity – if everyone is trying to win under the same criteria, they will tend to resemble one another.

After the pandemic, education beyond the age of 18 will, like everything else, be up for reconsideration. The government was in any case tinkering with the subject, following the recommendations of the 2019 Augar review that more attention be paid to non-university further education. A white paper on this is imminent. On universities, it could be a time to reflect on the ways in which they are not, after all, exactly like other businesses.

No comments:

Post a Comment