LOOK OUT! TROUBLE AHEAD.

Investors fear new Treasury auctions will set off repeat bout of selling

Investors are bracing themselves for a trio of large US government debt auctions this week, after a recent sale of seven-year notes flopped and set off a bout of frenetic trading.

The Treasury department is set to issue $120bn of new bonds beginning on Tuesday, selling $58bn of three-year notes, $38bn in 10-year debt and $24bn at the 30-year mark.

The auctions come at a tenuous time for bond markets, which have been beset by volatility as investors position for higher inflation, stronger growth and the prospects of the Federal Reserve pulling forward the timing of its interest rate increases. The Senate’s passage at the weekend of the $1.9tn stimulus bill, worth about 8 per cent of US gross domestic product according to Goldman Sachs, has bolstered this argument, analysts say.

“Investors will remain on pins and needles until the auctions are behind us,” said Gennadiy Goldberg, a rates strategist at TD Securities.

“The fear is that one of these auctions performs just as badly or worse than the seven-year, and that triggers another round of selling . . . which then brings another round of market instability, and then all of a sudden we're off to the races again.”

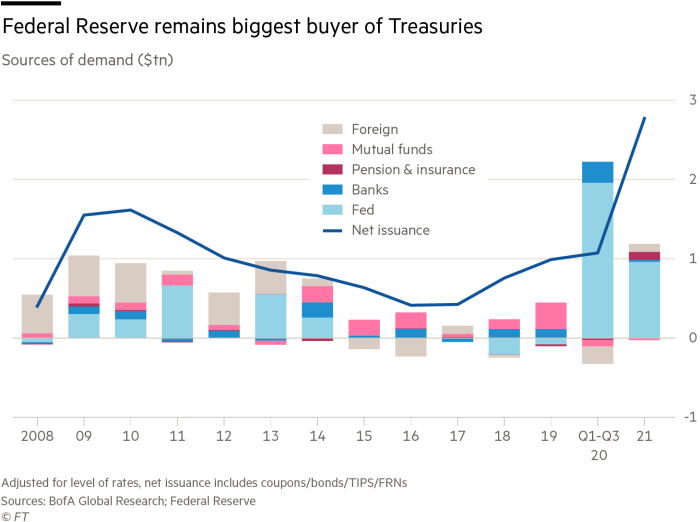

Large auction sizes, especially for longer-dated Treasuries, have become the norm since the onset of the pandemic, as the government has sought to fund the historic stimulus packages passed by US legislators since March. Investors last year absorbed the record supply with ease — save for a few small hiccups. And as fund managers clamoured to hold the debt, yields plumbed new all-time lows.

That changed last month, following a grim $62bn auction of seven-year notes on February 25. Investors retreated from the market in droves, forcing primary dealers — who underwrite US bond sales — to pick up a large chunk of the sale, exacerbating already wobbly trading conditions.

As prices fell, benchmark 10-year Treasury yields briefly blasted above 1.6 per cent, having traded around 1.4 per cent at the start of that week. It has now risen back to 1.6 per cent, following further selling early on Monday.

Market movements of this magnitude are noteworthy for the $21tn US government debt market, given its stature as the biggest and most liquid bond market in the world. Weak auctions also draw close scrutiny, and the current backdrop has left investors skittish of a potential repeat.

“People can't say that what happened [on February 25] won’t happen again,” said a managing director in the rates division at a large US bank, adding that they were “increasingly concerned” about the market’s ability to absorb the enormous amount of supply set to flood the market this year.

While Padhraic Garvey, global head of debt and rates strategy at ING, expects the upcoming auctions will see stronger demand — given that current yield levels are higher and therefore far more attractive to buyers than just a few weeks ago — he warned that any sign of weakness could have broader consequences.

“[If] the market shows severe indigestion, that would give the market more ammunition to push higher on yields,” he said.

Investors looking for assurance from the Federal Reserve were left wanting last week, after chair Jay Powell did not push back forcefully on the recent increase in Treasury yields.

“Until investors are comfortable knowing the Fed’s tolerance for higher rates, it is unlikely that most [Treasury] buyers will want to ‘catch the falling knife’ for higher [Treasury] yields,” said Meghan Swiber, a rates strategist at Bank of America.

Given the Fed’s reluctance to wade deeper into the Treasury market beyond its $80bn per month asset purchase programme, she warned a “significant” supply and demand imbalance of long-dated Treasuries would persist and keep upward pressure on rates.

One critical source of demand — foreign buyers — has already pulled back from the market. Recent data from Japan’s Ministry of Finance show that for the two weeks ending February 26, Japanese funds sold $34bn of foreign bonds, the bulk of which Ian Lyngen at BMO Capital Markets says were likely Treasuries. While market participants note that this is typical ahead of the upcoming close of the country’s financial year, it remains an open question to what extent these players will return.

“As a community, foreign real money can be very meaningful, because it can help to establish confidence,” said Deirdre Dunn, global co-head of rates at Citigroup. “With a dearth of activity . . . it can be harder for the market to find its footing.”

Banks have emerged as another important Treasury buyer, but their activity in the market may be more limited as well. US regulators must decide by the end of the month whether to extend a temporary rule change to the so-called supplementary leverage ratio (SLR), which allows banks to exclude Treasuries and cash reserves when calculating how much additional capital they need to hold. The policy was put in place in April 2020 in part to encourage banks to step in more forcefully to stabilise volatile markets.

“The idea that things could dislocate further is in recent memory,” said Dylan Roy, global co-head of fixed income trading at UBS. “Dealers who are thinking about the potential of SLR not being extended may become worried, which could have negative effects on market functioning and overall liquidity.”

No comments:

Post a Comment