TOURISM IS NOT INDUSTRY. TOURISM IS SERVITUDE

Todo Bajo el Sol: Spanish graphic novel explores history of mass tourism

Ana Penyas’s book tells story of three generations of a family whose lives reflect Spain’s socioeconomic transformation

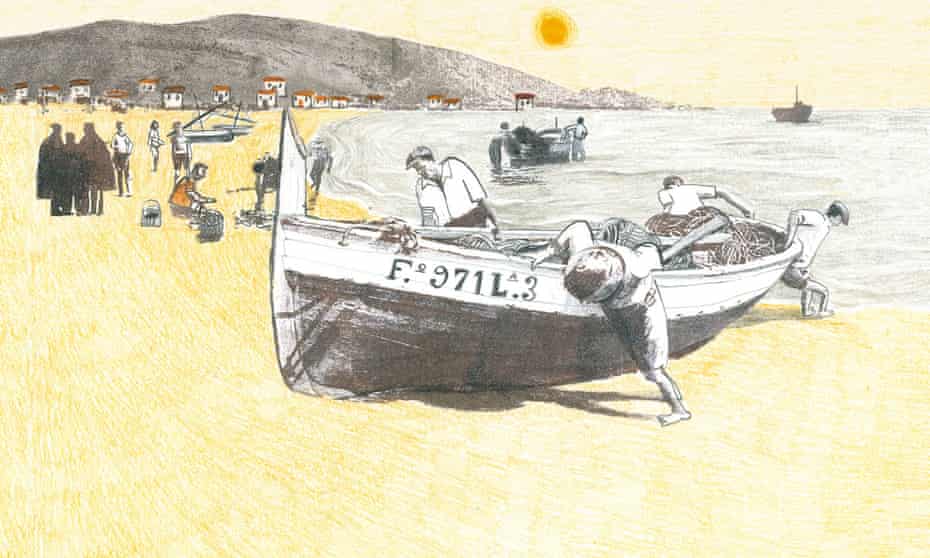

The opening pages of a new graphic novel charting Spain’s long, profitable and often counter-productive relationship with tourism show four fishermen hauling their boat on to a Mediterranean beach already in the early stages of occupation by the new breed of foreign holidaymakers.

While the fishermen, rendered in monochrome to reflect their looming obsolescence, heave their boat ashore, a tourist, drawn in colour, sits beneath the shade of his beach umbrella and prepares to study a guidebook produced by the Franco regime.

Similar juxtapositions permeate Ana Penyas’s Todo Bajo el Sol (Everything Under the Sun), which is dedicated to “those who had to abandon their hometowns and to those who ended up as strangers in their own land”.

Penyas, who became the first female author to win Spain’s national comic prize three years ago, said the idea for the book came to her in the spring of 2018, when the debate on sobreturismo – or over-tourism – was becoming inescapable.

By then, worries over gentrification, the proliferation of tourist rental properties, the number of huge cruise-liners pulling into Spanish ports and the dire employment conditions of some hotel-workers had raised questions about the sustainability of the the country’s tourism model. They had also led to anti-tourist graffiti and even attacks on hotels, tourist bikes and the odd tour bus.

“All that was going on, and I was also quite connected to movements to protect neighbourhoods from tourism and gentrification,” Penyas says.

“But when I thought about what I wanted to write, I knew I didn’t want to limit myself to a snapshot of that particular moment – not least because things can get out of date very quickly.”

The author, who was born in Valencia, eventually opted to follow the history of mass tourism in Spain from its inception under the Franco dictatorship in the late 1960s, through the heady days of boom and bust and into the current era of Airbnb and boutique hotels.

The story is told through three generations of the same family, whose lives reflect the profound social, cultural and economic changes Spain has experienced during the past 50 years.

“The family allowed me to a way to narrate all these things; they’re the cement that holds all these different issues together,” says Penyas.

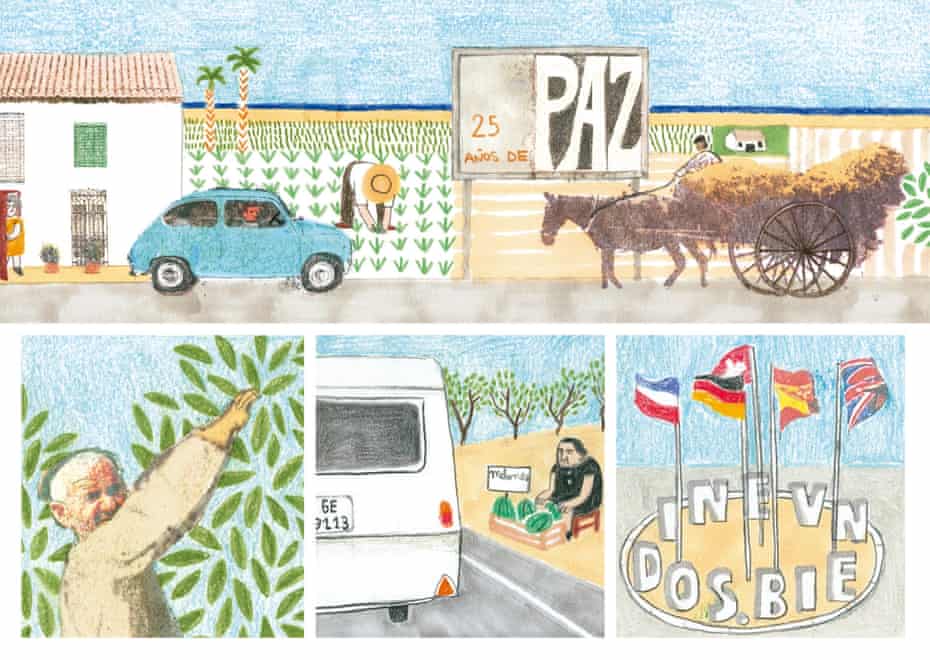

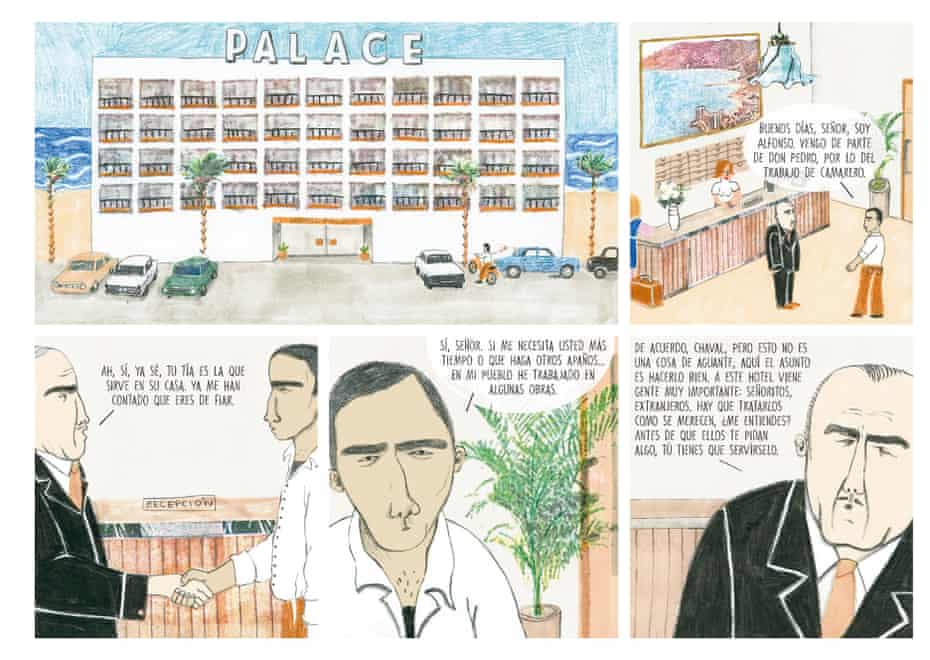

As the book begins, Spain is heading into the final years of the dictatorship and young people are leaving their inland homes and villages, lured to the coast by the promise of work in the new hotels.

The author uses overdrawn stills from a 1967 Swedish film called I Am Curious (Yellow), to highlight visitors’ attitudes to holidaying in Franco’s Spain. When asked if they are bothered about the regime, they reply: “Well yes, but I prefer not to talk about it”; “You forget about all that when you’re over there”; and “I don’t talk about politics when I’m on holiday.”

Penyas was keen to explore the Franco regime’s primary role in developing Spain as a tourist destination, and equally anxious to dispel the myth that the foreign visitors and their free and easy ways somehow posed an existential threat to the dictatorship.

“It wasn’t like that,” she says. “The regime was the driving force behind tourism and saw it as the raw material for Spain’s development. Any problems it caused were seen as the lesser of two evils. It also helped the Francoist mayors and the big families and hotel owners to get rich.”

Penyas says Francoism is “in the DNA of Spanish tourism”.

As the novel progresses, it takes in significant moments in the country’s recent history, from Spain’s entry into the EU in 1986 to the late 1980s La Ruta Destroy clubbing scene, and from the property boom of the 1990s to the devastating economic crash of 2008.

Villages retreat as tourism marches farther inland, developments are redeveloped, neighbourhoods reconfigured and young Spaniards – including one of the family’s daughters – head abroad to find work.

As Todo bajo el sol concludes, the first cycle of mass tourism has come to an end, its gaudy, 1960s knick-knacks now kitsch museum pieces in their own right. But the socioeconomic consequences are already irrevocable. On the last page, the mother of the family looks at the towering modern town around her and asks: “Do you remember when all this was orchards?”

The fundamental aim, says Penyas, was to look at the enduring impact of a sector that generates about 12% of Spain’s GDP and to explore the notions of “good tourism” and “bad tourism” – and people’s preconceptions about both. Or, as the author puts it: “I didn’t want just to be criticising Benidorm.”

Yes, there is high-end tourism and low-end tourism, “but at the end of the day, the dynamic is the same because they’re both created by the capitalist system” she says. “I really wanted that to be clear.

“Some people go: ‘No, but I travel in a different way.’ You can go and stay in a place in the centre of town, but you’ve got to wonder what had to have happened for it to be there. You don’t know.”

Late last month, the Spanish government announced an €11bn (£9.5bn) package to help tourism and hospitality sectors weather the Covid pandemic. The much-needed support is further proof of Spain’s decades-long reliance on foreign visitors.

“It’s been decided that loads of jobs will depend on this and this is how the economy’s been built,” says Penyas. “I hope things will change, but who knows? I’m not very optimistic.”

No comments:

Post a Comment