Hong Kong’s Avoidable Tragedy Is Complete

The future of the democracy movement in the city can be summed up in two words: It’s over. Could things have been different?

“It’s got to look democratic, but we must have everything in our control.”

These are the words of Walter Ulbricht, the future leader of communist East Germany, in 1945. Though separated by almost eight decades and 9,000 kilometers, their resonance will be immediately apparent to anyone who has followed the remodeling of Hong Kong’s electoral system.

The deed is done. President Xi Jinping signed orders on Tuesday that effectively neuter Hong Kong’s democracy, in contravention of the promises that China made when it resumed sovereignty over the former British colony in 1997. The changes shut out an entire political class from the right to compete in elections — a class that, the last time its popularity was put to the test, commanded the support of a majority of Hong Kong voters. Henceforth, only “patriots,” as defined by Beijing, will be able to stand. Candidates will be vetted by national security police and a committee whose decisions will be beyond legal challenge. The U.S., U.K., European Union and Japan have condemned the changes.

Ulbricht’s directive, attributed to him by the future defector Wolfgang Leonhard,

1 is a reminder that, behind the Communist Party’s self-proclaimed role as guardian of the soul of Chinese nationalism, is an imperative that unites Leninist one-party states across time and space just as tightly as any bonds of language, culture and history. Democratic structures and processes are a means to an end, there to provide a stamp of legitimacy to a pre-determined outcome. Choice is only an illusion. The real agenda is the party’s preservation of power.

The trouble now for Chinese authorities is that what they have done looks anything but democratic. In recent days, Hong Kong establishment figures from Chief Executive Carrie Lam on down have been at pains to stress that there will still be space for political opposition in the future. Seemingly, it has started to dawn on Hong Kong’s governing elite that Beijing has succeeded too well. The disparate alliance of pro-democracy candidates who intended to contest Legislative Council elections last year has not only been excluded; most of them are in jail, awaiting trial for conspiracy to commit subversion. There is unlikely to be a long line of aspirants willing to take their place.

The new electoral system, then, may be still-born — a moribund affair in which pro-party loyalists compete for the most fervent displays of allegiance, to the indifferent yawns of a disaffected public. Voter turnout, having reached a record 73.1% in the lower-level District Council elections that delivered a landslide to pro-democracy parties in November 2019, is almost certain to plunge. For a taste of the democracy that is heading Hong Kong’s way, look no further than the decision of the National People’s Congress on the electoral changes in mid-March: 2,895 delegates in favor, none against, one abstention.

How did it come to this? Whether Hong Kong’s path from the promise of “high degree of autonomy” to Communist Party rule by edict was pre-ordained from the start, or might have been avoided, is of importance – not only for the territory, but for the world. While it is a Chinese city, Hong Kong is also the place where the Communist system intersects most visibly with the open, liberal democratic values of the West. The city was a model for how a free, pluralist society could exist under the cloak of an authoritarian Communist government — an enlightened, mutually beneficial arrangement that mirrored how a politically unreformed China was welcomed into the global capitalist system four decades ago. This experimental model is now at an end.

***

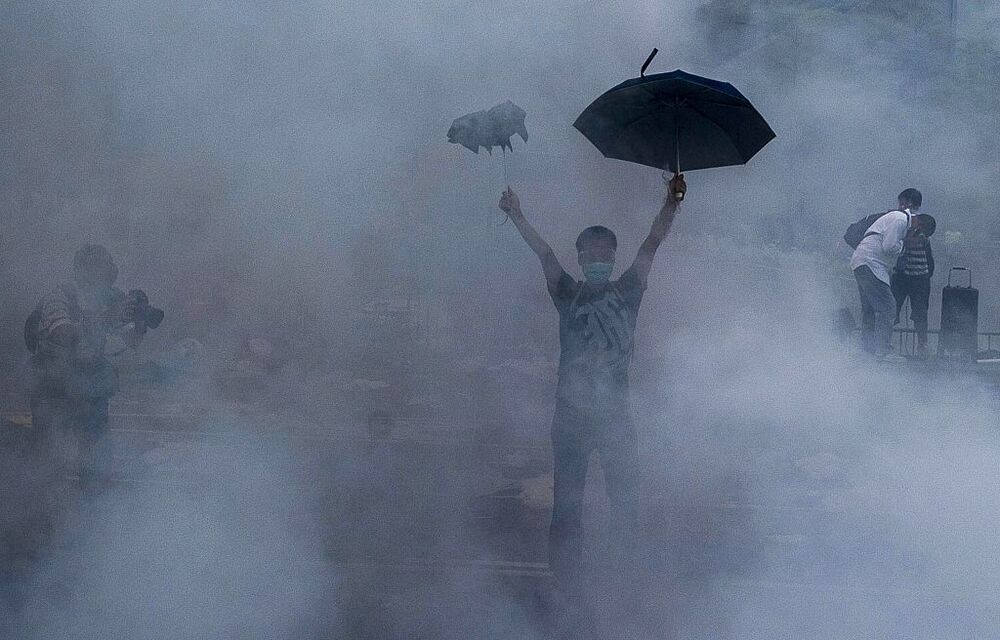

In Beijing’s telling, the changes were a necessary rectification of a flawed political structure that had failed to correctly implement Deng Xiaoping’s requirement for patriots to govern Hong Kong after 1997. Did China’s government not have legitimate concerns? After all, the city was convulsed by often violent protests during 2019. Some demonstrators waved the British colonial flag; many made no attempt to hide their contempt for a mainland Chinese system they regarded as corrupt, repressive and alien.

What it is necessary to appreciate is that the 2019 protests didn’t come out of a vacuum. They were the perhaps inevitable reaction to a creeping diminishment of freedoms that had begun years earlier, freedoms that were supposedly guaranteed under “one country, two systems.” While the immediate trigger was an extradition bill that would have allowed suspects to be sent to mainland China for trial, these tightening fetters spanned a plethora of events including: the disqualification of elected lawmakers; the suspected abduction of booksellers; plans for “patriotic” education in schools (the issue that brought imprisoned activist Joshua Wong to prominence as a 15-year-old in 2012, and which has now been resurrected following enactment of a national security law last year); and the de facto expulsion of a Financial Times journalist.

Having fostered the conditions for a backlash, Beijing used the resulting explosion as a pretext to bring its restive special administration region to heel. The waving of U.S. and colonial flags, and the voicing of pro-independence sentiments — understandably offensive to those who took pride in the city’s return to the motherland — helped Beijing to demonize protesters and justify the draconian nature of the clampdown. In fact, independence was never more than a fringe idea — recognized as utterly unrealistic by the broad mass of demonstrators. Their focus was always on preserving the freedoms and autonomy that Hong Kong had been promised by Beijing.

No matter. The Communist Party didn’t discriminate. Moderate pro-democracy politicians who accepted the post-1997 compact at face value and worked within the constitutional structure have been swept into the dragnet. Martin Lee, the 82-year-old founder of the Democratic Party who is often referred to as Hong Kong’s father of democracy, was branded absurdly as a “riot leader” by Chinese state media, extending the party’s long tradition of viewing him as a troublemaker. (Lee, a lifelong advocate of nonviolence, was charged with illegal assembly for taking part in a huge and peaceful unauthorized rally in 2019. On Thursday, he was found guilty along with six other pro-democracy figures.)

This is the denouement of a path that has undulated over the decades. At times, Beijing has appeared willing enough to live with the pan-democrats, as the grouping of pro-democracy parties is known. There have even been occasional signs of a limited rapprochement. But in a history pockmarked by miscalculations, misunderstandings and miscommunication on both sides, there is one date that stands out as particularly salient in influencing the passage of events: June 4, 1989.

***

Tiananmen set in train a series of steps that arguably led Hong Kong to its present juncture. In the pre-crackdown 1980s, a time of unusual openness and intellectual flexibility in mainland China, relations were amicable enough for Beijing to appoint Martin Lee and his Democratic Party co-founder, the late Szeto Wah, to the committee responsible for drafting the Basic Law, Hong Kong’s post-1997 constitution.

Among the committee’s tasks was drawing up a clause that specified Hong Kong’s responsibility to enact legislation to protect national security. This is the wording of that article of the Basic Law as it appeared in an April 1988 draft:

“The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region shall prohibit by law any act designed to undermine national unity or subvert the Central People’s Government.”

By its final, published form in April 1990, Article 23 had become this:

“The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region shall enact laws on its own to prohibit any act of treason, secession, sedition, subversion against the Central People's Government, or theft of state secrets, to prohibit foreign political organizations or bodies from conducting political activities in the Region, and to prohibit political organizations or bodies of the Region from establishing ties with foreign political organizations or bodies.”

This far more threatening wording reflected the anger and angst that the Communist Party felt over Hong Kong’s outpouring of support for the student democracy movement that met its end in the bloody suppression of June 4. The city’s people offered not only sympathy but material support to the students, inflaming the party’s longstanding fears that Hong Kong would be used as a base to subvert the Communist system on the mainland.

These anxieties were not unfounded. After all, Hong Kong had indeed been used repeatedly as a base for such activities in the past — by, among others, the Communist Party itself, before it came to power, as Steve Tsang, director of the SOAS China Institute in London, noted in A Modern History of Hong Kong. There was a dangerous logic in the Hong Kong people’s willingness to intervene on the side of the student movement. They wanted to preserve their way of life under “one country, two systems.” This should have implied non-intervention in each other’s affairs, Tsang wrote. Hong Kong couldn’t have it both ways.

The rewording of Article 23, after Martin Lee and Szeto Wah resigned from the Basic Law drafting committee (they were later expelled in any case), had fateful consequences. It left Hong Kong’s first post-handover government with a political hot potato that it dared not touch. When the administration of Chief Executive Tung Chee-hwa finally brought in legislation to fulfill Hong Kong’s obligations in 2003, half a million protesters poured on to the streets, fearing – correctly – that the national security law would prove a mortal danger to the city’s cherished freedoms. The legislation was withdrawn, and the government of Chinese President Hu Jintao, still mindful of Hong Kong public opinion, didn’t object.

That wasn’t the end of the story, though. The Article 23 controversy fed perceptions among conservative Communist intellectuals that the former colony was too wayward. Hong Kong needed to be reminded to “fully respect” the primacy of one country over two systems. The determination to bring Hong Kong into the fold was only stiffened when lawmakers in 2014 rejected plans to introduce universal suffrage for the city’s chief executive election via a mechanism that would have allowed Beijing to control who could be a candidate, leading to the Occupy Central movement. By then, the country had a new president in Xi Jinping.

“He has a vision for China, which includes Hong Kong,” said Tsang, who faults Hong Kong’s democrats for failing to unite and push the scope for autonomy when China was willing to be more flexible. “His vision is getting very close to one of wanting to project in China that there is only one nation, one people, one ideology, one party and one leader. Hong Kong is part of this one China and must be brought in line.”

***

For the democratic camp, it’s a bitter harvest. In recent years, veteran campaigners have had the worst of both worlds — scorned by Hong Kong’s young radicals for their moderate tactics, while simultaneously denounced as subversive accomplices and instigators of violence by their Beijing detractors. And at the end of it all, democracy has been canceled — at least in any form that is recognizable to people in liberal, multi-party systems.

“It’s very sad,” said Emily Lau, former chairperson of the Democratic Party, a phrase she used half a dozen times in the course of an hour-long interview several days before the electoral revamp was finalized. There’s a deep irony in Lau being regarded as too cautious. A pro-democracy firebrand, she first came to prominence in 1984 when taking U.K. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher to task for “promising to deliver over 5 million people into the hands of a communist dictatorship.”

The earlier generation of democrats were more circumspect in challenging Beijing because they remembered Tiananmen and knew what the regime was capable of. Many young protesters don’t have the sense of Chinese solidarity of their elders, identifying exclusively as Hong Kongers and being uninterested in what happens across the border — itself a cause of increasing alarm for the Communist Party. That led them to underestimate the risk of a harsh crackdown, according to Lau.

“If you poke a tiger in the eye and get it very angry, a lot of people are going to suffer,” said Lau. “You’ve got to be careful. You cannot just keep pushing.”

In retrospect, the Basic Law was written with a degree of creative ambiguity. Parties on each side were left to see what they wanted to see in it. The very term “democracy” means radically different things in the Chinese Communist and Western liberal contexts.

For decades, pro-democracy politicians could believe they were competing in something like a conventional multi-party system. The odds were stacked against them, via special interest “functional” constituencies that entrenched the power of pro-Beijing interests and a selection committee that did the same for the chief executive. Still, they could advocate for their beliefs and hold out hope that one day the system would be allowed to reflect the public will — given the Basic Law’s stated ultimate aim of universal suffrage.

The era of ambiguity is over. When democratic parties came too close to winning legislative power, it emerged that to do so would be considered subversion. Even though they might declare their acceptance of Hong Kong’s return to the motherland, proclaim themselves patriots, and eschew any hope of political change on the mainland, it didn’t make any difference. Beijing was never going to allow representatives chosen by the people to challenge its appointed administrators. Hong Kong’s democracy was a gilded cage. Elections weren’t there to decide the allocation of power, but to confer legitimacy on decisions that had already been made.

“It’s over,” is how Suzanne Pepper, a Hong Kong-based American political scientist and author of Keeping Democracy at Bay: Hong Kong and the Challenge of Chinese Political Reform, describes the future for the democracy movement. On her blog last week, Pepper, who has studied Hong Kong’s democracy movement for decades, said Deng Xiaoping had made it clear during the 1980s that he didn’t envisage a Western-style electoral system for Hong Kong and that multi-party elections after 1997 were not a good idea.

***

Something had to give. The social unrest in Hong Kong over the past seven years is the reflection of an ossified and complacent governing structure that is no longer able to respond adequately to the aspirations of the people. While the demands of the 2019 protesters were exclusively political, it is difficult to imagine that a widening wealth gap, overpriced housing and lack of economic opportunity didn’t contribute to the sense of disaffection among the city’s young people

One way to address this deficit would have been to make the political system more representative and responsive to the public will; in other words, to increase democracy. Beijing has decided to go the other way. The outlines of its program are coming into view: There will be a hardline approach to quashing dissent, while economic measures will be enacted to address livelihood issues and alleviate some of the sources of discontent. It is the stick-and-carrot formula that the Communist Party has followed in other restive regions such as Tibet, with some measure of success. Whether such an approach can work in Hong Kong, a city that is already rich, developed and educated, is open to question. Either way, the party now owns the results.

Beijing has taken control, as it always had the power to do, despite its promises. It’s worth considering what the People’s Republic of China has lost, though. The PRC’s international image has deteriorated badly in the past year, most notably because of the coronavirus. The Communist Party’s conduct in Hong Kong hasn’t helped. Its actions in such an open, transparent and internationally connected city have helped to draw more attention to the party’s much worse behavior in less visible regions such as Xinjiang. The evisceration of Hong Kong’s democracy will only feed perceptions that Beijing sees liberal, pluralist values as a threat to its own system, one that must be vanquished rather than accommodated. This augurs poorly for China’s prospects of influencing the world’s developed democracies and reversing the drift into a new cold war.

Could Hong Kong’s fate have been avoided? It’s tantalizing to wonder how events might have taken a different course if Tiananmen hadn’t happened. In this event, the more benign draft of Article 23 might have stayed in the Basic Law, enabling Hong Kong to pass its own, mild form of national security legislation rather than having the matter taken out of its hands by the NPC. A virtuous circle of increasing trust on both sides would have allowed Hong Kong to maintain its vigorously free and open society, a badge of pride for China and a sign that this emerging superpower was relaxed and confident enough to hold diverse political systems under its flag. Increased democratization as envisaged in the Basic Law would have obviated the need for protests.

This is almost certainly an illusion, though. “One country, two systems” has a shelf life of only 50 years, and is scheduled to expire in 2047. The ultimate objective has always been convergence with the rest of China. At best, if Tiananmen hadn’t happened or if the democrats had played their hand more skillfully, Hong Kong might have obtained an extension — perhaps a decade or so, in the estimation of SOAS China Institute’s Tsang. In the event, the advent of a strongman leader with a sense of historic destiny and the monthslong unrest of 2019 only accelerated the process. Hong Kong’s fate was avoidable, but only if the Communist Party chose to change its fundamental nature — and there has never been any sign of that. One-party Leninist states don’t share power, though they may create the appearance of being willing to do so as a matter of short-term expediency or public relations.

As a dead East German communist reminds us, the fix was always in.

No comments:

Post a Comment