One Reason U.S. Treasuries Don’t Seem That Worried About Inflation

Yields on government bonds might be agreeing with the Federal Reserve that price pressures are transitory, but they could also just be artificially low thanks to a constellation of arcane money market rates.

In the aftermath of the 2008 subprime crisis, regulators became determined to stamp out the kind of funding stresses that had brought the financial system to its knees. Efforts at shoring up the system included new liquidity requirements that required large banks to hold big buffers of ostensibly safe and liquid assets that could be used to protect against outflows.

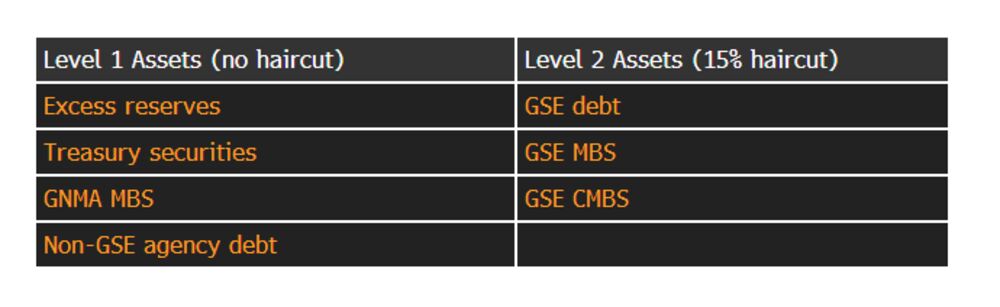

These portfolios typically fall under the umbrella of High-Quality Liquid Assets, or HQLA, but another way of thinking about them is as a form of bank bondage — a requirement that forces banks to keep large amounts of generally low-yielding securities like U.S. Treasuries (which can be used as collateral in the repo market), agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and reserves — on their balance sheets.

Like the famous Henry Ford maxim about customers being able to have “a car painted any color that he wants so long as it is black,” banks are able to tweak their HQLA portfolios so long as they consist solely of the things that fall under the strict regulatory definition of “liquid.” (Never mind, of course, that the rules arguably left banks more intertwined with the repo market in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis, a vulnerability which would come back to haunt them in 2020). You’ll typically find HQLA portfolios ebbing and flowing alongside available yield and interest rates.

We bring it up because one of the more interesting bits of market moves in recent weeks, or lack thereof, has been in U.S. Treasuries, where yields have remained stubbornly range-bound even as concerns over inflation seem to grow alongside the issuance of new U.S. debt.

There’s an argument to be made that the events of 2020 incentivized banks to snap up U.S. Treasuries for their HQLA portfolios in a way they haven’t really done before; buying $350 billion worth of the bonds over the past year or so. In other words, bank bondage could go some way towards explaining the apparently sanguine stance of the debt market towards the prospect of higher inflation and larger supply.

As the Fed Guy blog puts it:

“GSIBs are mandated to hold a sizable HQLA portfolio, but there is some degree of freedom in its composition. The highest quality Level I HQLA include reserves, Treasuries, and Treasury reverse repo. When reverse repo rates rose above IOR [interest on reserves] in 2018, GSIBs began reshuffling their HQLA portfolio out of reserves and into reverse repo. Now that IOR is at 0.1% and reverse repo is at 0%, GSIBs are shuffling their HQLA holdings towards Treasuries. Some are also significantly increasing their holding of Agency MBS, which is a slightly lower quality HQLA (Level 2a).”

The implication here is that a technical source of demand — banks buying U.S. Treasuries to satisfy liquidity requirements — has effectively put a lid on yields and potentially stripped them of some informational value regarding exactly what the market thinks of inflation risks. U.S. Treasury yields might be agreeing with the Federal Reserve that price pressures are transitory, but they could also just be artificially low thanks to a constellation of arcane money market rates.

This source of demand could change or disappear entirely if something were to come along and knock the delicate balance of rates and incentives that has combined to herd the world’s biggest banks into U.S. Treasury bonds. It’s worth noting, of course, that the effective fed funds rate’s slow march towards zero has plenty of people talking about the possibility of the central bank changing the amount of interest it pays on excess reserves.

If that were to happen, U.S. Treasuries might suddenly have a whole lot more to say about inflation.

No comments:

Post a Comment