Italy and Sweden show why Biden must fix the immigration system

Opinion by Fareed Zakaria

September 30, 2022 at 7:54 Sydney Time

Italy and Sweden are about as different as two European countries can get. One is Catholic, Mediterranean, sunny and chaotic; the other Protestant, northern, chilly and ordered. Over the decades, they have had very different political trajectories. But now, both are witnessing the striking rise of parties that have some connections to fascism.

In each country, this rise has coincided with a collapse of support for the center-left. And it all centers on an issue that the Biden administration would do well to take very seriously: immigration.

Giorgia Meloni, likely the next prime minister of Italy, is a charismatic 45-year-old politician. Her campaign was a familiar attack on the forces of globalization and a comforting story that she would somehow bring back the good old days before George Soros ruined everything.

In a video that went viral, she says she is proud of all things that the globalists want you to be ashamed of — being Christian, a mother, Italian, etc. And a big part of her policy program is immigration. “Nations only exist if there are borders and those are defended,” she says, promising a naval blockade if that is what it takes to stop the flow of illegal migrants from the Mediterranean.

The appeal of the far-right Sweden Democrats also centers on immigration. The party talks a great deal about the rise of crime, gang violence and abuse of the country’s generous welfare state. But its main campaign proposal was a 30-point plan designed to turn Sweden, which has arguably one of the most generous immigration systems in Europe, into the most restrictive. It is "time to put Sweden first,” says Jimmie Akesson, the dynamic 43-year-old leader of Sweden Democrats.

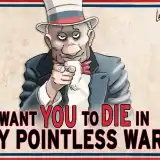

There is lots of demagoguery in these two politicians and their parties, but there is also an important truth at the heart of their appeal. Immigration in many countries in Europe is out of control.

By “out of control,” I do not mean it is too high. It’s impossible to say what the right number is for any given country. I mean that migration is now largely taking place in a chaotic manner, with massive surges in flows, rampant human smuggling and crime, and a total breakdown of the legal system by which countries evaluate and admit applicants. Sweden’s population is now about 20 percent foreign-born, which is much higher than in the United States, where that number is about 14 percent.

America is different from Europe. American identity is political, while European countries’ national identities, at least historically, have been based on ethnicity, religion and culture. Either way, there are limits to how many people a country can absorb.

About 5 percent of the U.S. population was foreign-born in the 1970s. Since then, that percentage has almost tripled. Even so, people can be convinced that large numbers of outsiders can be assimilated and absorbed. What enrages them is the sense that people no longer become immigrants through a process that the host country controls but rather by crossing the border illegally, claiming asylum status, gaining entry and then simply sticking around. And that fear is justified.

The U.S. asylum system has broken down. It was designed after World War II, in the wake of the Holocaust, to take in people who faced immediate and dire persecution. Today, many people seeking asylum face hardships much like those that have traditionally led people to seek a better life here: poverty, crime, disease, dislocation. They are deeply deserving of dignity and decent treatment. But anyone claiming asylum for only those reasons is abusing the system in an effort to bypass the normal immigration process.

And that process in the United States is now utterly dysfunctional. It was already clogged and understaffed, and President Donald Trump deliberately jammed it up even more, to the point that routine business visa applications from countries such as India can take months; students cannot enter the United States even after getting scholarships; and work-visa applications now rest on the chance of applicants winning a lottery (literally).

The Biden administration is going into the midterm elections with a strong hand. It could be undone by this one issue. It has found an intelligent way to speed up the consideration of asylum requests, though it feels woefully inadequate to the backlog at hand. There are about 744,000 asylum cases pending.

Biden needs to find a way to demonstrate that his administration is taking control of immigration in general and the border in particular. Then he can propose the obvious compromise that could appeal to most Americans: a better, faster, more predictable legal immigration system but a tougher, more effective way to restrict illegal immigration. Or else, the populist right will use this issue to keep gaining ground in the United States just as it has in Italy and Sweden.