One Year On, Putin Must Wish He'd Read His Herodotus

What the war in Ukraine has proven is that all of us, starting with the Russian president, have been arrogantly wrong about almost everything.

No intellectual humility in this space.

Photographer: Alexey Nikolsky/AFP via Getty Images

A big lesson all of us — but especially people in power — should learn from Vladimir Putin’s attack on Ukraine one year ago has to do with intellectual humility, and the disastrous consequences of its absence. That’s because not only the Russian president but almost everybody has been wrong, wrong, wrong about almost everything.

Putin was most obviously wrong in his perception of Ukraine as a country. Wallowing in the quack historiography of charlatans, he had convinced himself that Ukraine isn’t a nation in its own right, but a mere appendage of Greater Russia. Over the past year, Ukrainians proved the opposite: that they’re fiercely independent, with an identity defined largely against the Kremlin’s imperialism.

From this hallucination, Putin went on to stumble into hundreds of other explicit and implicit fallacies, delusions and errors. He assumed, for example, that the Ukrainians would either greet the invading Russians as liberators or cut and run at the first sight of a Russian tank. Instead, they’re fighting like heroes.

Putin was just as sure that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy would either be eliminated within hours of the attack, or would take his family and flee abroad. Instead, Zelenskiy not only stood his ground but became one of the most inspirational leaders in history.

Putin was also wrong about the West. From his previous aggressions — against Georgia in 2008, or Crimea and Donbas since 2014 — he concluded that NATO and the European Union would never coalesce to stare him down. He was sure that Western capitals would shrink from his nuclear bullying, and that they’d never take risks on behalf of countries in “his” rather than “their” sphere of influence.

Moreover, he was certain that he had, with his long and deliberate pipeline diplomacy, rendered countries like Germany so dependent on Russian oil and gas that they wouldn’t dare oppose him on anything. So he had no doubt that the West, decadent and effete as he saw it, would once again put profit and comfort above principles such as national sovereignty and the international peace order.

Wrong on all counts. NATO — always a fractious alliance — has rarely been as united as it is today, and is poised to grow by another two members, Finland and Sweden, in direct response to Putin’s invasion. The European Union and its partners in the Group of Seven have been passing one sanctions package after another. Germany, in the course of the war’s first year alone, has cut its dependence on Russian gas from more than half of its imports to precisely zero. Above all, the West has been giving the Ukrainians more weapons each time Putin has escalated — howitzers, missile defenses and now the biggest, meanest battle tanks.

Putin also misread the rest of the world. He was sure, after he and his fellow anti-Western autocrats in Beijing declared a “friendship” with “no limits” just before his attack, that China would always have his back. But his counterpart, Xi Jinping, felt taken aback by the invasion, and was horrified by Putin’s subsequent threats. The Chinese haven’t turned against Russia yet. But they’ve subtly begun limiting (so much for “no limits”) Putin’s options. Meanwhile, countries formerly under Putin’s thumb, such as Kazakhstan — far from cowering in awe at his might, as Putin expected — are securing new assurances from Ankara, Beijing and elsewhere.

So Putin was wrong to believe the stories he heard from his chosen historians, advisers, generals and minions inside Russia, as from his partners and sycophants abroad. He understood nothing about reality, or how people in his physical presence would filter it for him. Most importantly, he didn’t even understand enough to recognize that as a phenomenon in itself.

***

The rest of us were also wrong in uncountable other ways. In the months leading up to the attack, most people in the West, as in China and the rest of the world, felt sure — despite the American intelligence showing the Russian troop buildup — that Putin would never invade, that he was once again just bluffing. Even many Russians didn’t see the attack coming, down to the very troops slated to be the vanguard crossing into Ukraine. Zelenskiy himself couldn’t yet imagine a scenario as outrageous as the one that became reality. Nobody, it turned out, understood Putin’s state of mind.

Once the attack was underway, the vast majority of self-proclaimed or genuine Western “experts” just knew that Russia would overwhelm its smaller and weaker neighbor. I recall debates in Germany a year ago that centered on the question of whether the invasion would last two days or four. The upshot of such discussions was invariably that arming the Ukrainians was pointless, because they’d lose anyway.

Completely wrong, as we now know, because we misread both sides. First, we grotesquely underestimated the martial prowess and will of the Ukrainians, from their uncanny ability to “MacGyver” (that is, improvise) to their defiance in the face of Russian genocide. The first clue that we had a flawed perception came when the Americans offered to whisk Zelenskiy out of Ukraine and he replied: “I need ammunition, not a ride.”

Second, we all vastly overestimated the Russian army. We had been counting its soldiers, tanks and other hardware. But we didn’t see its dysfunction, caused by endemic corruption but also bad culture and leadership — especially at the level of non-commissioned officers — and sheer incompetence in tactics and strategy.

We were just as wrong about Putin’s KGB-trained mind. Many of us assumed, after years of watching his trolls subverting Western elections and seeding conspiracy theories, that he’d always win propaganda wars against open societies. He hasn’t. More generally, a lot of us felt sure that he was a master tactician and strategist, always one step ahead of his enemies. One year on, most of the world understands that he’s not an evil genius — just a liar, a brute, and a war criminal.

***

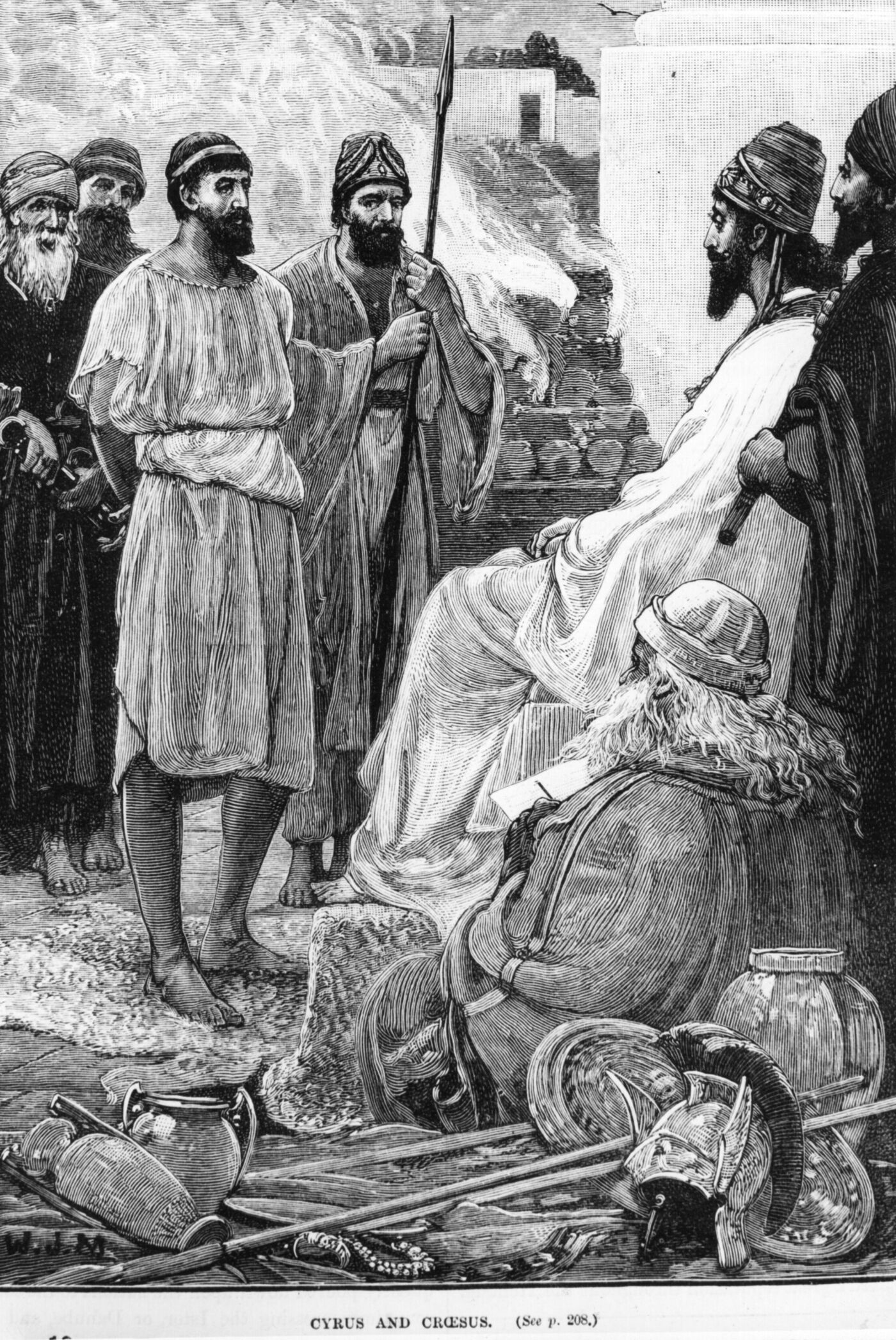

The phenomenon underlying Putin’s disastrous decisions — let’s call it intellectual hubris — is hardly new. In fact, it’s timeless. One of the first thinkers to describe a historical figure like Putin was Herodotus, with his account of the Lydian king Croesus, who ruled and failed in the sixth century BCE.

Croesus was famous for two things. The first was his vast wealth in gold and other glittery things (hence the phrase “rich as Croesus”) — the ancient equivalent of Putin’s hydrocarbons. The second was his hubris. Croesus ruled over probably the world’s richest land at the time, in today’s Anatolia. But when a new warlord to his east, later known as Cyrus the Great, seized power in what would become the Persian Empire, he felt both threatened and tempted.

So Croesus sent emissaries to Delphi to ask several questions of its famous oracle. The crucial one was: Should he go to war against the Persians? The oracle, channeling the god Apollo, replied that if Croesus did attack, “he will destroy a great kingdom.”

Off to war he went, his doubts dispelled. A few turns later, Croesus’ armies were defeated, his capital was sacked, his wife committed suicide, and Croesus found himself tied up atop a lit bonfire, about to be burned alive, with the triumphant Cyrus watching. What could possibly have gone wrong?

***

Croesus’s problem, like Putin’s, was that he lacked intellectual humility. This trait doesn’t necessarily have much to do with modesty as such. It’s instead defined as an “awareness of the limits of one’s knowledge” and of the “limitations of one’s viewpoint” — or, if you prefer, an appreciation of one’s own fallibility. In Croesus’ case, he couldn’t wrap his mind around the oracle’s deliberate ambiguity — which great kingdom will he destroy? — because he was so sure he knew.

People who do have intellectual humility, by contrast, will be open to, and indeed seek out, alternative and contradictory views. Croesus, as Herodotus tells the story, could easily have lent an ear to a Lydian sage named Sandanis, who warned that they were about to “march against men who wear breeches of leather” and drink water rather than wine — fearsome savages, in other words. We Lydians, Sandanis argued, already have everything we could want; we have nothing to gain from attacking the Persians, but everything to lose. Croesus ignored him.

Similarly, Putin, to test his own theories about the inherent “unity” of Russians and Ukrainians, might have listened not only to historians on the loony right — such as Rasputin look-alike Alexander Dugin — but also to countervailing scholars, such as Yale University’s Timothy Snyder, who would have told him a rather different story. As Putin gathered his war councils in preparation for the invasion and kept hearing about the alleged superiority of his armed forces, he might also have consulted outside expertise to learn about his weak spots.

Such intellectual hubris is often potentiated by “groupthink.” Developed by the social psychologist Irving Janis in the 1970s, that concept describes the phenomenon of intelligent people making terrible decisions as a group. Janis used examples such as the failed Bay of Pigs invasion and America’s war in Vietnam, but his insights apply equally to any number of other fiascoes, including Putin’s attack on Ukraine.

Even — or especially — when the individuals involved are smart, Janis found, they tend to fall into several predictable traps. As a group, they’ll surrender to an illusion of invulnerability. This mindset helps them rationalize whatever decisions they make. In the process, they’ll never question their own morality, because any group they’re part of must self-evidently be good. They’ll also stereotype not only their opponents but all outsiders. Some of them will voluntarily play the role of “mindguards,” blocking the flow of contradictory information. At some point, the group will in effect adopt self-censorship. Eventually, its members will have the illusion of unanimity.

Seen in that light, the meetings of his security council that Putin convened in the runup to the invasion looked like staged parodies of groupthink. At one point, he gathered his advisers in a Tsarist rotunda inside the Kremlin, seating them on uncomfortable chairs at a great distance from his massive desk, and had them, one by one, repeat his own opinions back to him. “Are there any differing points of view?,” Putin finally asked. Apparently not.

Another curious aspect of intellectual hubris is that it increases as the stakes get higher and the pressure grows. In one study, the more people were made to feel threatened, the less willing they were to consider opposing opinions, and the more wary they became of people outside their group. Putinism certainly seems to wallow in paranoia — about an allegedly hostile West, opposition at home, or whatever else. This, too, is a bad guide to wisdom.

***

The first lesson from history, it’s often said, is that we never learn the lessons of history. Each generation brings forth new characters Herodotus would recognize. But we’d be foolish to pass on the opportunity for reflection offered by this tragic anniversary.

A leader like Xi Jinping springs to mind. It’s an open question whether he’s actually planning to invade Taiwan during this decade, but he’s certainly been sounding more belligerent than his predecessors. Yet he’s also been watching the disaster engulfing his supplicant in the Kremlin. Has the past year made him more intellectually humble?

We can’t know, but we can hope. If he’s wise, Xi is now wondering what he doesn’t know — about his own army’s weaknesses, about how Taiwan might resist, how the US and its allies would respond, and even how far the Communist Party and the mainland Chinese people would go to back him. If he has oracles, they may well whisper to him that if he invades the islands he too will destroy a great civilization. Which, though?

Putin and Xi remind us that autocracies are at particular risk of intellectual hubris. By definition, these systems are closed mental universes that require conformity and punish free thinking. Before Xi consolidated his power, the Chinese Communist Party seemed aware of this shortcoming and eager to correct for it, by encouraging meritocracy and debate within its ranks, if not in society at large. Xi appears to have put an end to that. That’s a bad sign.

Open societies, by contrast, at least have the advantage of intellectual heterogeneity. More people in more institutions feel more free to speak more of their minds, even when the results are eccentric. Wise leaders — in business, government, education, journalism and all other domains — will encourage rather than fear such motley diversity. But that’s more easily said than done, once egos enter the equation. Recall that Irving Janis used mainly American case studies in his research about groupthink.

We’d also do well to guard against intellectual isolation — for instance, the so-called echo chambers on- and offline. Putin has in recent years progressively withdrawn into a private world, out of fear of Covid and other phobias. There he surrounded himself only with the same small cast of characters, who blew him a phenomenological bubble he could no longer peer through.

Not least, we should be especially vigilant whenever we make decisions while under threat or pressure. As we now know, that’s when we most urgently need to consider alternatives and outside views — but are instead most prone to closing our minds.

Most historians believe that Croesus burned to death on that pyre in front of Cyrus. But Herodotus and the ancients didn’t think that made for an edifying story. So the historian had Croesus cry out to Apollo, the god who had got him into this mess. Moved, Apollo wept until his tears put out the fire. Cyrus saw this, became intrigued, and granted a favor. Croesus chose to send emissaries to Delphi again, to ask why the oracle had led him so disastrously astray.

The oracle replied that it had only told him the truth — a great empire was destroyed. But the Pythia added that it behooved Croesus to “take right counsel, to send and ask whether the god spoke of Croesus' or of Cyrus' empire. But he understood not that which was spoken, nor made further inquiry: wherefore now let him blame himself.” At last Croesus understood — and “confessed that the sin was not the god’s, but his own.”

No comments:

Post a Comment