Ukraine Is a Test for Future Wars and the West Is Failing

European allies and even the US aren’t living up to promises for boosting defenses to counter China’s aggression.

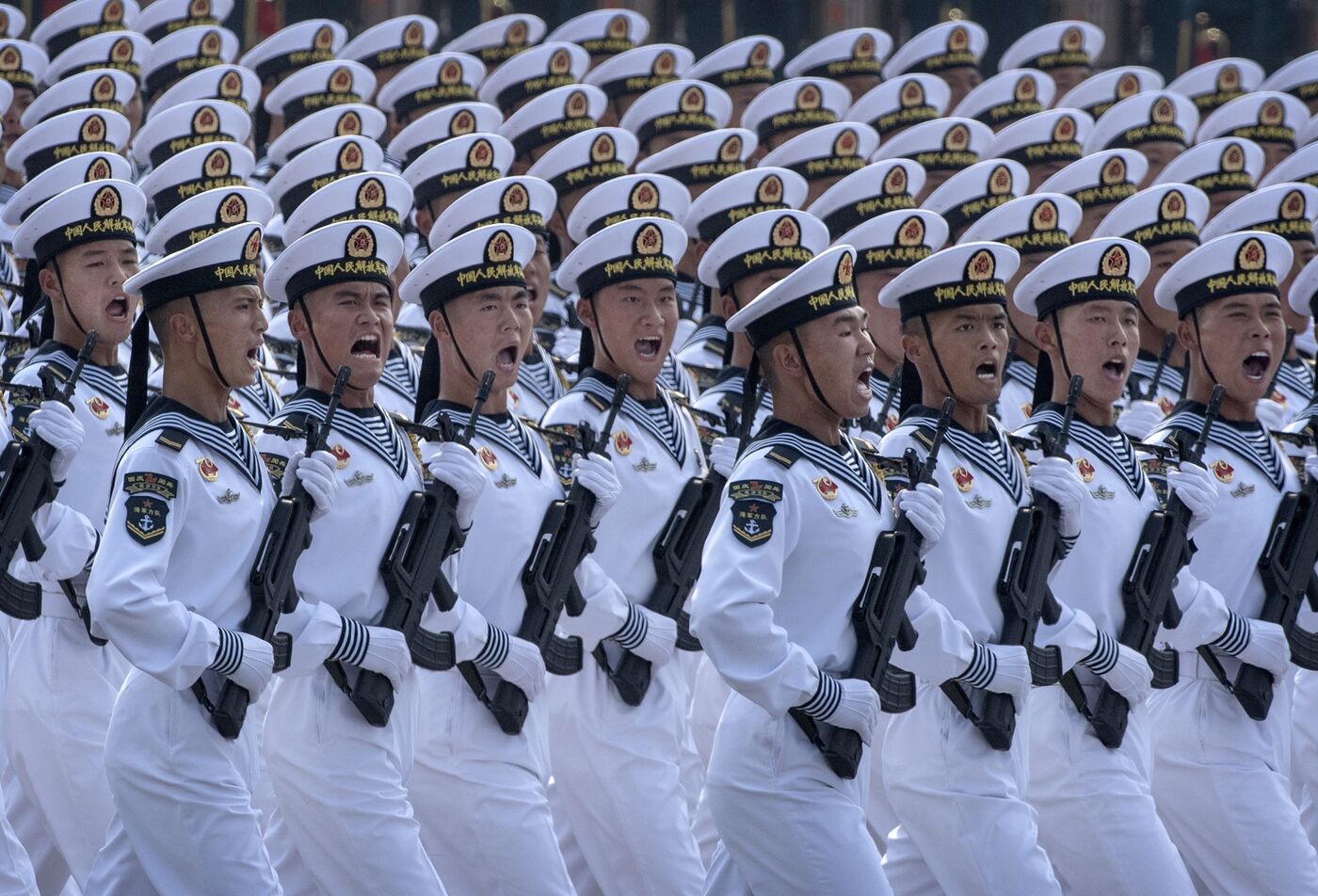

Photographer: Kevin Frayer/Getty Images

Since its outset, Russia’s war on Ukraine has posed two fundamental strategic questions. First, would Ukraine survive as an independent state? Second, would the democratic world use the war wisely, to get ready for the even greater dangers ahead?

Fifteen months into the conflict — and as Ukraine’s long-awaited counteroffensive gets underway — we can be cautiously confident in answering the first question. Unless Ukraine is simply abandoned by its Western backers, it will emerge from this conflict terribly battered but not defeated.

Yet the second question is arguably more important to the future of global order, and the answer is far less certain.

Crises, the true cliché goes, offer opportunities as well as challenges. They can shake nations out of strategic torpor and pierce persistent denial about looming threats.

During the Cold War, a hot war in Korea was the crisis that made the free world. The shocking, unprovoked invasion of a sovereign country convinced the West to ditch its bargain-basement approach to containment and forge the military shield that would keep the Soviet Union in check. America and its allies needed a similar jolt before February 2022.

The US had for several years rhetorically committed to waging great-power rivalry with China and Russia. But on issues from defense to trade, it had struggled to assemble the policies needed to compete effectively. In Europe, Germany and other countries were increasing their addiction to Russian energy. In Asia, Japan and Taiwan, among other places, were taking an inexcusably leisurely approach to arming themselves for a potential conflict with Beijing.

That changed, for a while, with Russian President Vladimir Putin’s attack on Ukraine. The invasion was a Korea-like assault on the norms of a civilized world; it was a reminder that great-power competition can quickly turn into violent conflict. Ukraine’s tragedy was the free world’s warning.

Washington and its allies heeded that warning by bleeding Russia in the 21st century’s most lethal proxy war. They gave Ukraine the support it needed to save itself and devastate Putin’s army in the process. The war also produced a strengthened, expanded North Atlantic Treaty Organization, as Finland and Sweden sought entry into the alliance and countries across Europe pledged to significantly hike military spending.

The conflict, combined with the worst Taiwan crisis in a quarter-century, also produced a harder line toward China. The US and a few allies imposed sanctions cutting Beijing off from high-end semiconductors and the inputs needed to make them — a potentially devastating shot in the tech cold war underway. Japan laid plans to nearly double defense spending over a half-decade; countries up and down the Western Pacific pulled closer to Washington and to one another. Rather than dividing the West, the war hardened alliances on both of Eurasia’s margins.

Yet these steps were merely down payments on a full-fledged strategy to protect the democratic world from autocratic predation. And the urgency of crafting that strategy has faded, ironically, as Ukraine has held its own.

In Germany, Chancellor Olaf Scholz has sought to wriggle out of an earlier promise to spend 2% of gross domestic product on defense. Taiwan’s self-defense preparations have accelerated, but it still isn’t arming itself with anything like the alacrity one would expect from a country in existential peril. Next year’s presidential elections could return to power the Kuomintang party, which favors a softer line on Beijing and could slacken Taiwan’s military preparations.

If lethargic allies are part of the problem, in some cases Washington isn’t doing better.

The recent debt ceiling deal actually cuts defense outlays in real terms, an act of strategic lunacy at a time when the risk of war in the Western Pacific is clearly rising. A much-touted, long-delayed executive order on outbound US investment in China — in other words, on America’s funding of firms that are helping the People’s Liberation Army prepare for war — appears likely to be modest in scope and effect.

Nor has President Joe Biden’s administration done much to fill the biggest hole in America’s China strategy: the lack of anything comparable to the Trans-Pacific Partnership. That trade deal, which America animated and then abandoned under President Donald Trump, was meant to promote economic growth in Asia and give the region’s economies an alternative to reliance on Beijing. (After the US withdrawal, the other 11 parties formed a rump organization called the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership and, irony of ironies, China has applied for membership.) To call the administration’s replacement, the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, “vague” would be polite understatement.

It isn’t all bad news, by any means. Poland is transforming itself into a major military power, which will anchor the anti-Russia coalition in Eastern Europe for years to come. The recent commitment by the Group of Seven to collectively combat Chinese economic coercion is welcome, even if what will actually emerge is still uncertain. But if there are areas where real progress is being made, there are too many where urgency has given way to business, politics and bureaucracy as usual.

That’s no way to use a crisis — or to win the contest for the future of global order. The war in Ukraine gave the democracies a chance to get ahead of impending challenges from a bellicose China and an angry, embittered Russia. They may not get another.

No comments:

Post a Comment