China’s Biggest Brokerage Restricts Short Sales After Stock Rout

2:14

China’s largest brokerage has suspended short selling for some clients in mainland markets amid a deepening rout in the nation’s stocks, according to people familiar with the matter.

State-owned Citic Securities Co. has stopped lending stocks to individual investors and raised the requirements for institutional clients earlier this week after so-called window guidance from regulators, said the people, asking not be identified discussing a private matter.

Citic Securities didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Chinese shares have extended declines this year with no sign of a let-up after a harrowing 2023, and the Shanghai Composite Index is having its worst start to a year since 2016. While it’s not immediately clear how many Chinese brokerages are restricting short sales, the move signals China’s eagerness to put a floor under the market, after earlier efforts including state buying of bank shares failed to lift sentiment.

In another sign of official attempts to boost stock prices, trading activity in some major exchange-traded funds surged on Thursday — pointing to potential buying by state institutions.

Beijing has a history of limiting short selling at times of market volatility, with an aim to avert a downward spiral in stocks. As recently as October, regulators tightened rules on short selling to halt declines.

The strategy hasn’t always worked. In its last stock boom and bust cycle in 2015, China restricted short-selling to force out day traders, whose selling and buying of stocks on the same day were seen as fueling “abnormal fluctuations.” The market continued its slide over the following months.

Read more:The moves in October, and a later order in November for brokerages to cap the size of their securities lending businesses, also failed to arrest a slide in stocks. The value of shares sold short has dropped 61% from a 2021 peak to 67 billion yuan ($9.3 billion) on Wednesday, its lowest since August 2020, before a mild increase on Thursday.

The benchmark Shanghai Composite Index on Thursday dipped below the key 2,800 psychological level to its lowest since April 2020, before recovering some ground at the close. That contrasts with a rally in Japanese stocks, which have seen frenzied ETF purchases by Chinese investors. The market capitalization gap between China and Japan has narrowed to the lowest since July 2020.

— With assistance from John Liu

China Is Buying Up US Farmland, But Just How Much Isn’t Clear

1:24

America is seeing more and more of its most fertile land snapped up by China and other foreign buyers, yet problems with how the US tracks such data means it’s difficult to know just how much.

Foreign ownership and investment in US farmland, pastures and forests jumped to about 40 million acres in 2021, up 40% from 2016, according to Department of Agriculture data. But an analysis conducted by the US Government Accountability Office — a non-partisan watchdog that reports to Congress — found mistakes in the data, including the largest land holding linked with China being counted twice. Other challenges include the USDA’s reliance on foreigners self-reporting their activity.

Outside ownership of US cropland is drawing attention from Washington as concern rises about possible threats to food supply chains and other national security risks. Lawmakers have called for a crackdown on sales of farmland to China and other nations.

“Without improving its internal processes, USDA cannot report reliable information to Congress or the public about where and how much US agricultural land is held by foreign persons,” the report said.

The GAO made six recommendations, including that the USDA share more timely and complete data with the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US, an interagency panel led by the Treasury Department that reviews foreign business deals.

That Thunder Out of China Is Loss of Confidence

The building blocks of gobal investor belief in the world’s second-largest economy are being pulled away, one by one.

To get John Authers' newsletter delivered directly to your inbox, sign up here.

Shanghai Surprise

Everyone was braced for trouble in Chinese markets this week. The election in Taiwan threatened to be a major geopolitical flashpoint and scare off investors. Then Saturday’s presidential result came in largely as expected, the status quo on the island largely seemed intact, China said little or nothing about it. Chinese stocks traded calmly on Monday. Since then, they’ve tanked.

The progress of Hong Kong’s Hang Seng Index tells the story well:

In broader context, investors seem to have suffered a cathartic loss of confidence in China wherever they were based. Onshore shares quoted in Shanghai and Shenzhen (represented by the CSI-300 index) dropped to a five-year low. Chinese stocks quoted in Hong Kong and the US have fared far worse. Such lack of faith is an important event in itself:

So what happened? It’s best to start with the economy.

- The Economy

Wednesday brought a slew of data that painted a bleak picture of China’s recovery. From the persisting property sector downfall as home prices fell the most in almost nine years, to continued deflation risks after a measure of broad price changes recorded its longest stretch of quarterly declines since 1999, it’s possible the numbers prompted investors to lose patience.

To get the numbers in a long-term context, take a look at Bloomberg’s estimate of nominal GDP in dollar terms over the last 30 years. Mexico, which in 1993 was just slightly bigger on this basis (with only a 10th of the population), is included for comparison. China’s growth has been extraordinary, the defining shift in the global economy of the last generation. But its period of uninterrupted growth looks now to be over. Once the weakening yuan is taken into account, it’s actually contracting slightly in dollar terms:

Sure, China hit its official growth target for the year, but it failed to shake off several of the problems that have been dragging down growth. Gross domestic product grew 5.2% in line with expectations. (Premier Li Qiang, in fact, revealed the number in Davos, Switzerland, a day before the official figures were published.) China’s brief post-pandemic rebound last year ran out of steam within months. That gave way to hopes that a disappointing recovery would prompt authorities to open the spigots for another big round of stimulus. That rosy scenario has also now been dashed. Li gave his clearest signal yet that Beijing won’t resort to huge stimulus to revive growth amid the worst deflation in decades:

To Crit Thomas, global market strategist at Touchstone Investments, there may be some wisdom down the line in the decision to hold off. “They’re kind of in a box,” he said in an interview.

In some respects, not pouring on the gas to the Chinese economy, probably, in the longer term, is the right thing to do. You have way too much debt. Why would you throw more at that? And I think President Xi has realized this quite some time ago when he created those three red arrows for the property sector.

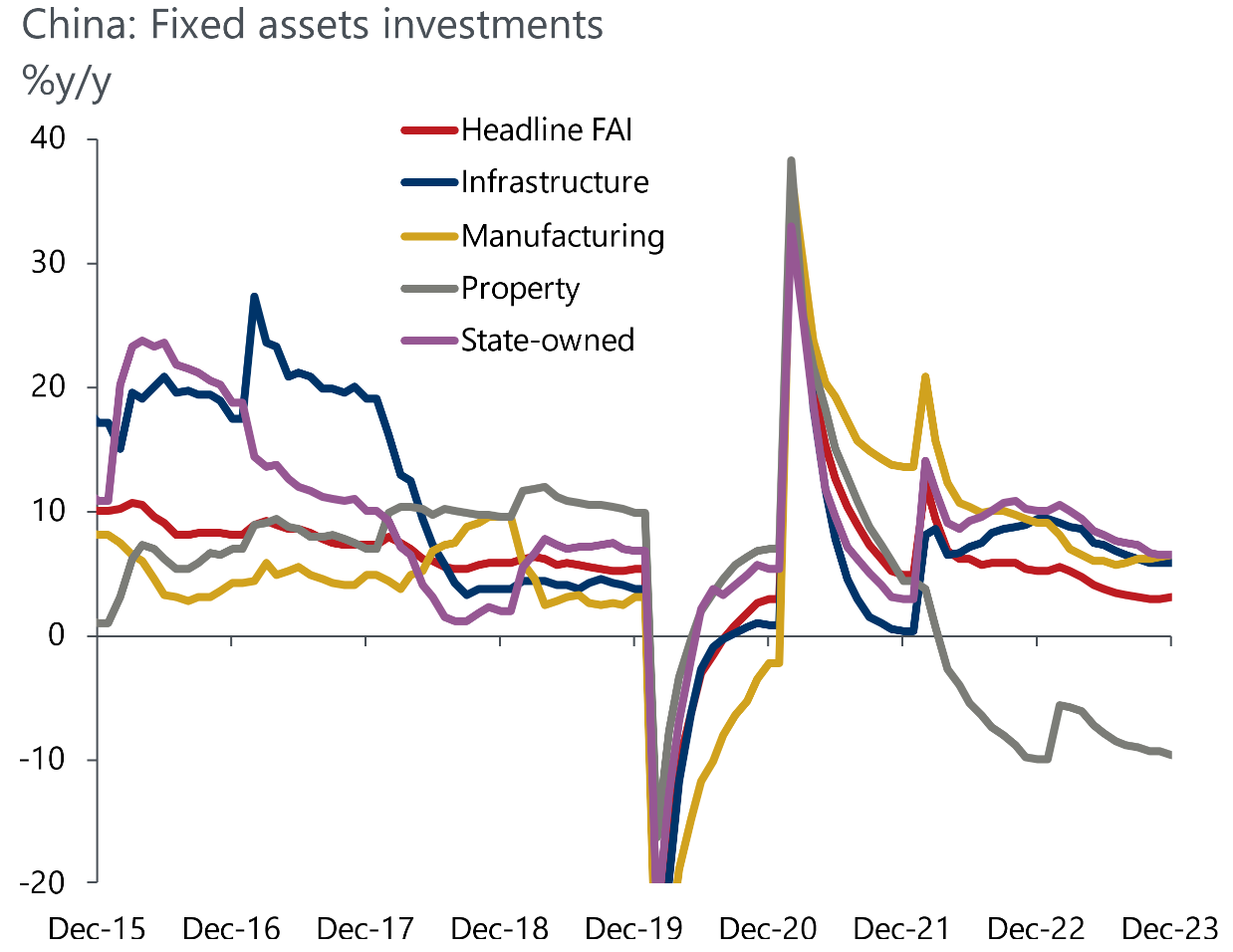

Dampening the recovery, among others, is indeed the property sector. It’s been a major headwind for the economy. Officials have been increasing pressure on developers struggling to repay debts and complete projects. Even if China has vowed to meet “reasonable financing needs” of all property developers, some were still uncertain how such efforts to ease cash crunches will pan out. As this chart from Oxford Economics’s Louise Loo shows, the property sector has been by far the weakest link in China’s investment:

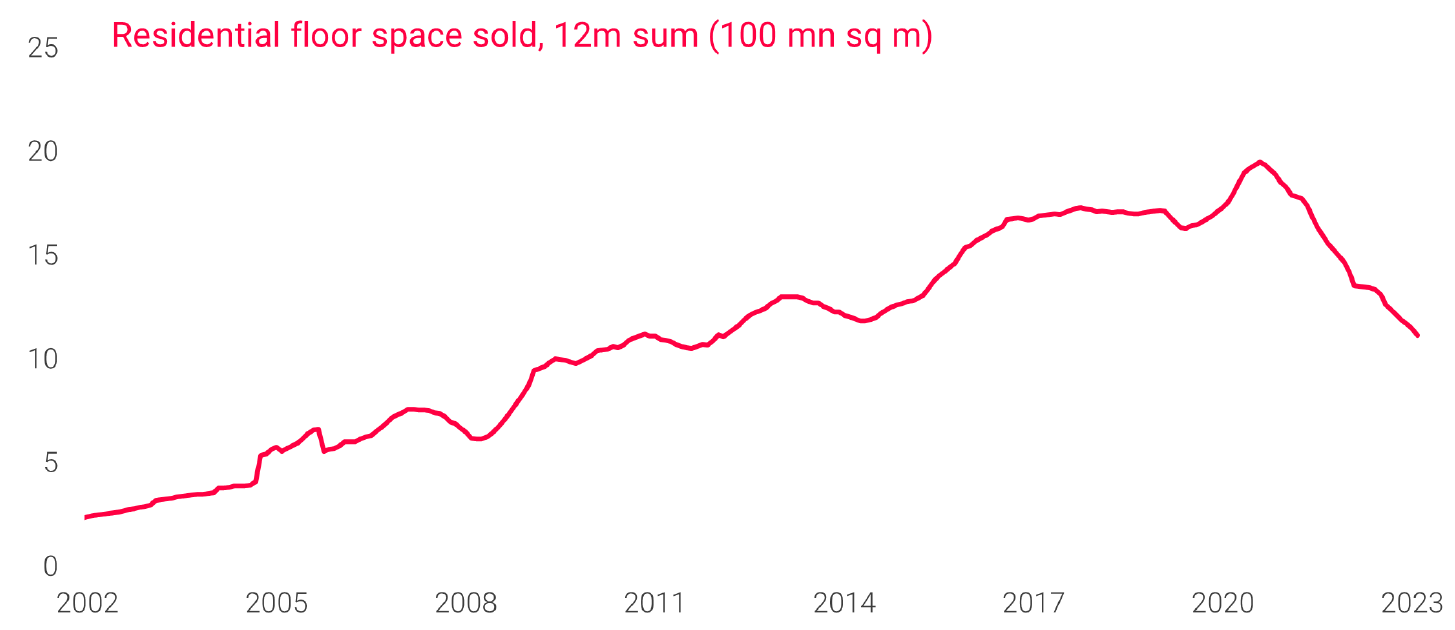

For another indication of just how brutal this decline has been, TS Lombard offers this chart of the amount of residential floor space sold over the last 20 years. Sales are now back down to their levels a decade ago:

Property weakness makes consumers reluctant to spend their money and attacks confidence. While retail sales rose 7.4% year-on-year in December, they missed analysts’ estimate of around 8%. Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Marvin Chen noted:

The details are a bit more concerning, with retail sales below expectations and unemployment ticking up, which suggests consumer sentiment remains low… Sentiment remains the key drag on the economy and markets, which is more difficult to stimulate than something like fixed asset investment.

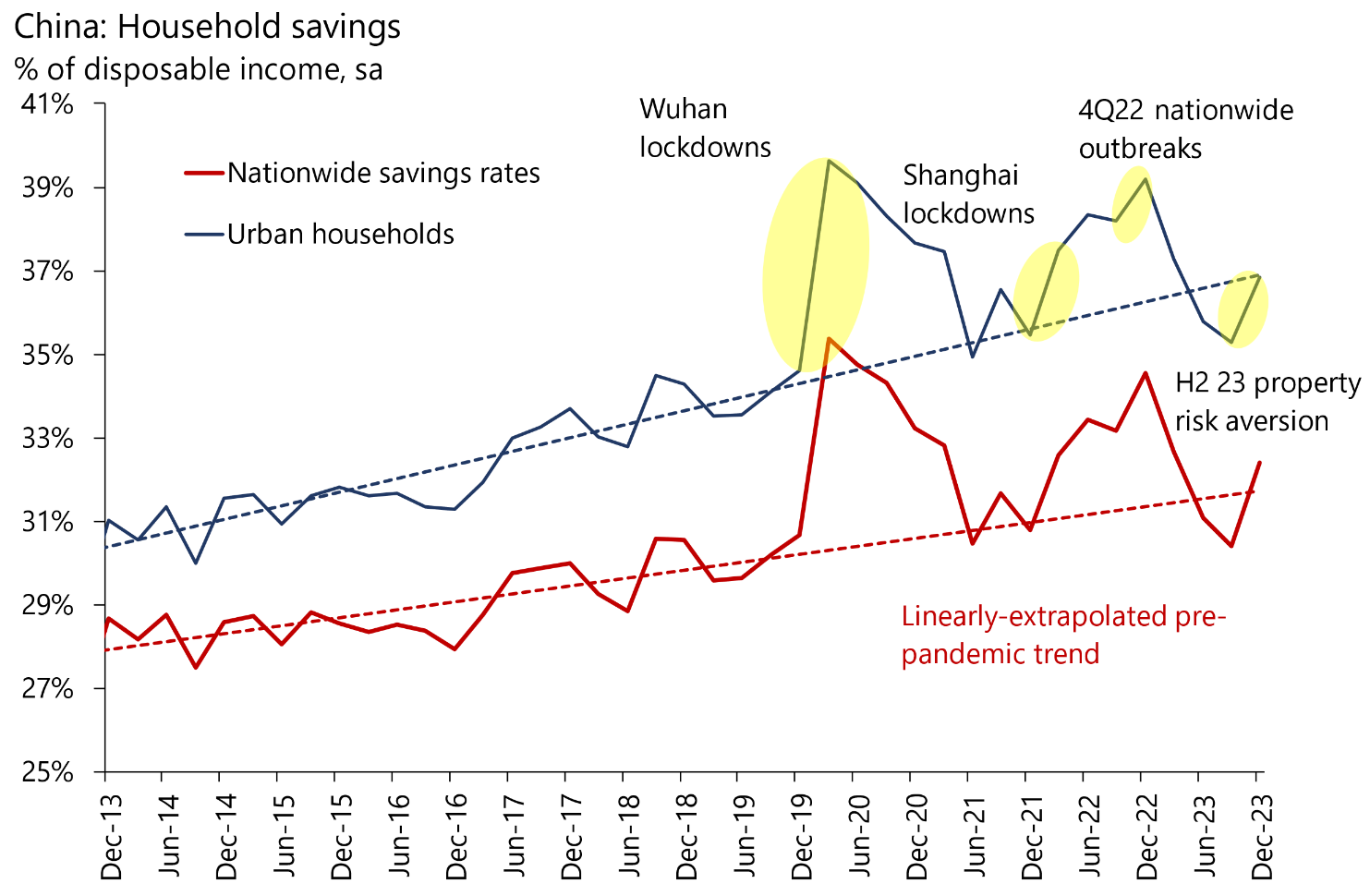

As it is, China’s consumers have increased their savings rate again, less than a year after the economy reopened from the draconian Covid-Zero lockdowns. Falling property prices, making people feel less financially secure, may be to blame. That’s illustrated by Oxford Economics:

Pascal Koeppel, chief investment officer at Vontobel Swiss Financial Advisers who oversees around $10 billion, remains cautious toward China overall. But unlike some, he views the real estate issue to be an isolated problem: “I think the Chinese government can handle it.”

More pressing to him is the shift of production out of China, or so-called nearshoring. “China is really producing a lot of goods. And because of this very restrictive Covid policy in the last years and the supply chain problems that we have seen, global companies are starting to diversify their supply chains — that comes with certain costs, obviously.”

- International Response

The selloff came as power brokers were enjoying their annual powwow at the World Economic Forum at Davos. Jamie Dimon said investors considering making a move into the country had to be “a little worried” because “the risk-reward has changed dramatically.” In a CNBC interview, the longtime chief executive of JPMorgan Chase & Co. said that while China has been “very consistent” in opening up to financial-services companies, calculating the potential upside for US firms has become more complicated.

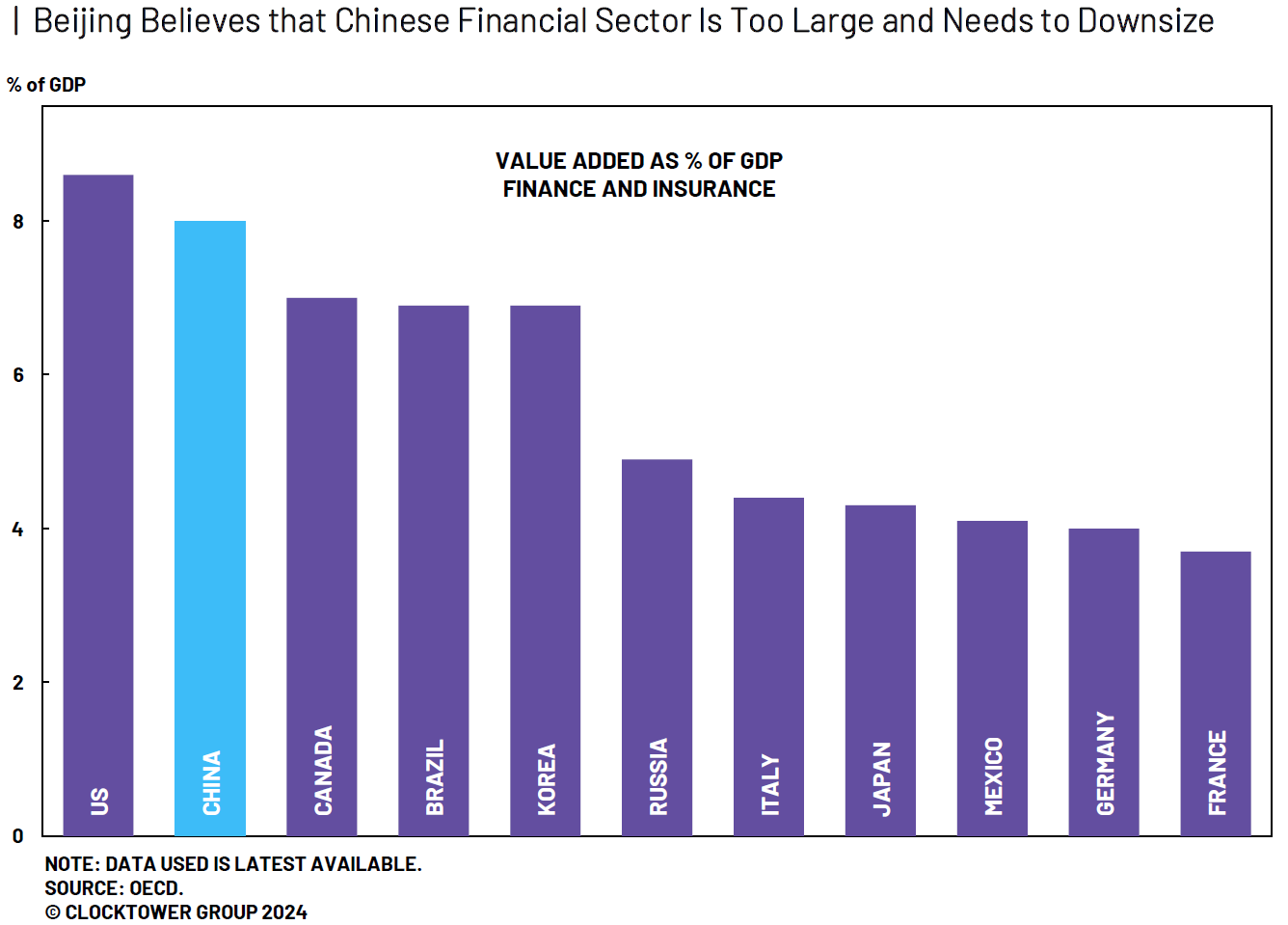

Beijing is now turning attention to reducing the size and power of the financial sector. Marko Papic of Clocktower Group pointed to Tuesday’s high-level work conference on financial services and said it was “widely perceived by investors as a prelude to a comprehensive crackdown on the financial industry.” He pointed out that the conference concluded that “(regulators) must severely punish corruption and strictly prevent moral hazard while resolving financial risks” and that the industry must “prioritize righteousness over profits.”

China’s authorities have long been preoccupied by the possibility of a local replay of the crisis that followed the 2008 Lehman Brothers bankruptcy, and appear determined to stop the financial sector from getting even larger. At present, Papic points out, it’s almost as dominant within China as the US banking system is at home:

Positively, China may be recognizing the risks of an over-financialized economy; more negatively, it is retreating further from the capitalist model and accepting lower growth. Wherever it falls on this continuum, the direction of travel is deterring investors.

Kevin Rudd, former prime minister of Australia, thinks the notion that China’s economy has peaked is “flawed” due to the untapped potential of consumer demand. “I’ve never really accepted the thesis that you see written in various parts of the world about peak China — that somehow China’s economy is peaking, slowing and then heading toward something worse,” Rudd told a panel in Davos. “As long as the Chinese consumer has confidence in the future, then the economy will continue to grow reasonably well.”

This will be harder, however, if China has to face a further round of sanctions and trade tariffs. That leads to another explanation for the selloff: blame Donald Trump. He is known for hostile rhetoric toward the country. Tuesday trading started in China just as Trump was being called the winner of the Iowa caucuses, and the selloff began. Trump himself has happily claimed responsibility. “I felt very badly for them,” he said. “You know why? Because I won Iowa.”

Leaving aside whether a presidential candidate should be happy about causing a stock market to plummet, it’s not obvious that China would regard a second Trump term as so much worse than more of Joe Biden. As this chart shows, MSCI’s China index more or less exactly matched its US index during the four years after Trump’s surprise victory in 2016; since Biden’s victory in 2020, they’ve lagged by 60%:

The Trump trade war of 2018 damaged the Chinese stock market, but it was nothing compared to the damage that has been done as the US has tried to clamp down on national security issues under Biden. Another indicator that China’s competitiveness is suffering already — its currency is its weakest since the Global Financial Crisis. When taking account of inflation, its tumble in the last two years has been dramatic:

Conceivably, this could grow even worse under a second Trump administation. The former president’s words certainly stirred up worries about China. But a lot of bad news seems to be in the price.

- Investability

After the selloff, are Chinese stocks now so cheap that it’s safe for foreign investors to try getting involved again? The extent of political uncertainty still makes any investment speculative. “There’s going be parts of it that’ll be investible,” Touchstone’s Thomas said. “You certainly need to pay attention more to the language that’s coming out of the political side of things. And it can be fickle. I certainly wouldn’t want to stock-pick my way through China.”

One constructive suggestion, from Freya Beamish of TS Lombard, is to concentrate on those Chinese stocks that pay reliable dividends. This is a measure that cannot be obfuscated. We know whether or not a company is paying out cash. If it does, we know that it has a reasonably positive attitude to corporate governance, and that it must be producing some cash flow. The dividend version of the CSI-300, focusing on regular dividend-payers, has been impressively stable during this selloff:

Another point, made by Louis-Vincent Gave of Gavekal, is that even if politics has rendered China uninvestible for Americans and Europeans, that doesn’t apply universally. China is so cheap that it could lure new investors to give the market another look, he says. “After all, China might appear uninvestible to a US pension fund or a European insurance company. But to a value-conscious Middle Eastern sovereign wealth fund or to the family office of an Indonesian tycoon, China today might look anything but.”

- About Those Rate Cuts...

Amid the negativity, it’s odd that nobody is billing the possibility of importing deflation from China as a positive in the war against inflation in the west. It should buttress the chance for rate cuts later this year. People may have been disinclined to view it that way because the big selloff in Shanghai and Hong Kong came amid surprisingly “hot” data in the US, and an alarming inflation print in the UK.

The data shouldn’t be that alarming — the miss was not that great, and inflation is still less than half its peak. So the reaction in the gilts market tends to confirm that prices had been taken too far and too fast, and that investors were already nervous about whether they had piled in too enthusiastically. This is the 10-year gilt yield since the beginning of last year:

China may yet help tame western inflation. But for the time being, it looks as though those disinflationary bets went a little too far.

—Reporting by Isabelle Lee

Survival Tips

The defamation trial of Donald Trump in New York is a dispiriting business, but it has had the positive effect of giving everyone an excuse to talk about the great legal comedy My Cousin Vinny. Whether the Trump lawyer Alina Habba is really like the character played devastatingly by Marisa Tomei in the movie or not, it’s just great to return to scenes like this, and this, and this.

More From Bloomberg Opinion:

- Beth Kowitt: Corporate America Should Amp Up the Volume on DEI

- Bill Dudley: Have No Fear of the Fed’s $7 Trillion Stash

- Hal Brands: Ukraine’s Desperate Hour — Is US to Blame for Kyiv’s Struggles?

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter.

— With assistance from Isabelle Lee

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the author of this story:

John Authers at jauthers@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

Patrick McDowell at pmcdowell10@bloomberg.net

No comments:

Post a Comment