Europe’s Sleeping Giant Awakens

Politics in Berlin has undergone a cataclysm that no one saw coming.

Late last year, when Angela Merkel was still German chancellor, I asked one of the most astute foreign-policy thinkers in her government about the country’s worrying dependence on authoritarian powers and the reluctance of its political class to reconsider these relationships.

At the time, Berlin was poised to inaugurate a new gas pipeline from Russia, and Germany’s biggest companies were announcing major new investments in China. But Merkel was on her way out, and the question on many minds was whether a leadership change might bring about a shift in Germany’s approach. The German official was skeptical.

“Freedom does not mean as much in Germany as it might in other places,” this person told me, speaking on the condition of anonymity in order to candidly discuss German political mores. “If the trade-off is between economic decline and an erosion of freedoms, Germany could well choose the latter.”

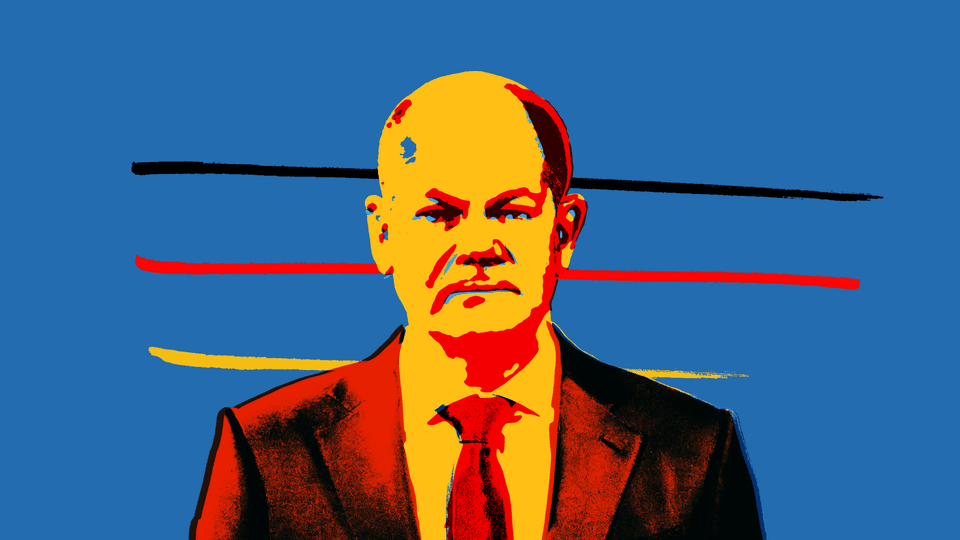

Over the weekend, Merkel’s successor, Olaf Scholz, rose to the podium in the Bundestag and proved otherwise, putting freedom first in a stunning response to Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine. In doing so, he shattered German foreign-policy taboos dating back to the founding of the Federal Republic more than 70 years ago.

Scholz announced that Germany would end its dependence on Russian gas, spend an additional 100 billion euros on its military, and deliver hundreds of anti-tank weapons and Stinger missiles to Ukraine in order to help its overmatched military counter Russia’s all-out assault. Germany may also be forced to extend the life of its nuclear plants to fill the energy gap created by the halt to Russian gas supplies.

Each one of these decisions represents something of an earthquake. Taken together, they are a political cataclysm that no one saw coming—not from a novice chancellor known for his caution, not from a coalition of German parties with pacifist roots, and certainly not from a government led by the Social Democrats, with their history of close ties to Russia.

“We are entering a new era,” Scholz told Parliament. “And that means that the world we now live in is not the one we knew before.”

From Washington, it can be hard to appreciate just how big the shifts are that we are witnessing in Germany, and so it helps to look back at where the country has come from.

As the German diplomat Thomas Bagger eloquently explained in 2019, Germany emerged from the fall of the Berlin Wall, German reunification, and the collapse of the Soviet Union convinced that it had finally landed on the right side of history. Democracy was sweeping across Eastern Europe, chasing authoritarian strongmen from power. What Vladimir Putin—a KGB agent living in the East German city of Dresden when the wall fell—has described as the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe” of the 20th century was a rebirth for Germany, and proof, in Bagger’s words, that history was bending toward its brand of liberal democracy. The end of the Cold War also meant peace, and with it came a radical reduction in German defense budgets.

At the same time, the country was emerging as an industrial powerhouse, sucking up Russian gas and selling its world-leading machine tools to a rising China, all while relying on a security umbrella provided by the United States. There were bumps along the road—Europe’s financial crisis, Russia’s annexation of Crimea, Middle Eastern terrorism, and an influx of refugees—but none shook Germany’s confidence in its own model and worldview.

Then came Brexit, the election of Donald Trump, and the growing realization that “Wandel durch Handel ”—Germany’s mantra of change through trade—was not working so well after all. China was still snapping up German cars and technology, but it had turned into an authoritarian surveillance state with global ambitions, as well as a formidable economic competitor.

Merkel, more than a decade into her long reign, offered hints that all was not right. In a Munich beer tent in 2017, following one of her first encounters with Trump, she acknowledged that Germany might not be able to rely on the United States as it once had. But she never conveyed to ordinary Germans that the pillars of Germany’s postwar model were crumbling, or made clear to them that they might have to pay a price for the upheaval to come.

One of her last major foreign-policy acts was to force through a European Union investment deal with China over the objections of the incoming Biden administration. A last-ditch attempt to keep intact an old world based on rules, unfettered trade, and cozy big-power relations, it collapsed within three months in a flurry of sanctions.

Still, Scholz sent the message to voters during his election campaign that nothing much needed to change. He ran as the natural heir to Merkel, even adopting her signature diamond-shaped hand posture to reassure Germans that “Mutti” (Merkel’s motherly nickname) would live on in the form of a bald, soft-spoken 63-year-old man from her party’s rival. He spoke about the need to relaunch former SPD Chancellor Willy Brandt’s signature “Ostpolitik” policy through greater outreach to Moscow and Beijing.

But as Harold Macmillan once said during his tenure as British prime minister, “events, dear boy, events” have a way of challenging leaders in ways they could not have imagined. Scholz’s initial reaction to Putin’s saber-rattling was to play it down. Nord Stream 2, the Russian pipeline to Germany that had long faced fierce resistance from EU partners and Washington, was an apolitical “business project” that should be decoupled from the sanctions debate, Scholz told the world in mid-December, even as Putin massed troops on the Russia-Ukraine border. (Not for nothing, the previous SPD chancellor, Gerhard Schröder, has morphed into a gas lobbyist for Putin since departing office in 2005.)

Scholz’s sudden about-face over the past week, as Russian troops rolled into Ukraine, was in part a reaction to the overwhelming pressure his government had come under—both within Germany and among Berlin’s closest allies—after weeks of foot-dragging. But the pressure alone does not explain the measures Scholz announced, which go far beyond what anyone could have expected from a politician known for his Hanseatic reserve.

The moves are an acknowledgment that the world has indeed changed, that Germany must invest heavily in its own defense, that it must pay an economic price to defend its values, that it cannot remain a larger version of Switzerland in a world of systemic rivalries. In making them, Scholz has gone against the tide of his own party, that of the German business establishment, and what many assumed to be the preferences of the broader German population. And yet the parties in his coalition have backed him, and the German media are hailing his boldness. On the same day Scholz made his announcements, more than 100,000 people converged on Tiergarten, next to the Bundestag, to show their solidarity with Ukraine.

In one fell swoop, Scholz has liberated himself from the cautious Merkel mold that got him elected. Merkel, too, made momentous decisions during her 16 years as chancellor, but none was quite as seismic for Germany’s place in the world, or as potentially costly for the economy, as the ones that Scholz has announced less than three months into his chancellorship. It is an irony that the taboos that grew out of the country’s shameful World War II past could be smashed only by another war in the heart of Europe.

What comes next is uncertain. Implementing Scholz’s measures will be challenging, and he can expect resistance from deeply entrenched German interest groups. Fixing the underfunded German Bundeswehr won’t happen overnight. And replacing Russian gas supplies is a daunting task.

It is unclear what the implications are for Berlin’s relations with Beijing, which has sealed a “no limits” partnership with Putin and refused to condemn his aggression. China is markedly more important to the German economy and its leading businesses than Russia is. And its threat to Germany’s security, though slow-burning rather than in-your-face like Moscow’s, is no less real or concerning.

But the die has been cast. “Peace and freedom in Europe don’t have a price tag,” German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock said last week. It is freedom over prosperity after all.

No comments:

Post a Comment