Face masks made with allegedly forced Uighur labour in China are being sold in Australia

At least two Australian companies have imported stocks of masks from manufacturer involved in labour program criticised as ‘highly coercive’

0

Face masks manufactured at a Chinese factory using allegedly coerced Uighur labour are being sold in Australia, the Guardian has learned.

Australian demand for face masks is expected to skyrocket in coming weeks, after Victorian authorities mandated their use in metropolitan Melbourne and the Mitchell shire, and recommended them for regional areas.

At least 200,000 face masks made by Hubei Haixin Protective Products Group Co Ltd in China and then sent to multiple distributors in Australia are in question, and consumers may be unwittingly purchasing masks made by allegedly coerced labour.

Experts are now warning local face mask distributors, governments and consumers to ensure their supply chains are not tainted by factories using forced Uighur labour.

Earlier this year, a report by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute thinktank identified a series of factories linked to a program of forced labour involving 80,000 Uighurs, a persecuted minority subjected to mass detentions, surveillance and restrictions on their cultural and religious beliefs – in what critics say amounts to cultural genocide.

The report described the labour program as “a new phase in China’s social re-engineering”, and found evidence that some Uighur workers were shipped far from their homes to factories across China between 2017 and 2019, including in some cases directly from detention centres.

The evidence suggested highly coercive conditions, including constant surveillance, the banning of religious observance, limited freedom of movement, segregated dormitory living, supervision by “minders”, mandatory “ideological training”, anthem-singing, flag-raising and Mandarin classes.

One of the factories named in the ASPI report belonged to the Hubei Haixin Protective Products Group Co Ltd, which manufactures personal protective equipment in Hubei province, central China, and exports to a range of countries, including Australia.

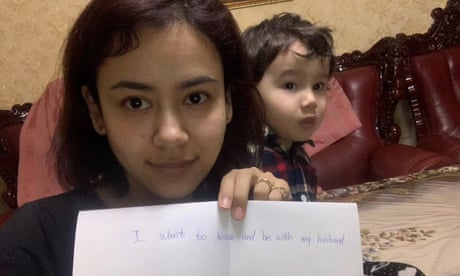

According to the state-run Hubei Daily newspaper, the company, in agreement with the Chinese government, transported 131 Uighur women aged 19 to 31 from their home in Xinjiang to the company’s factory in Hubei by train earlier this year, a distance of more than 3,200km.

The women must participate in flag-raising and anthem-singing ceremonies, learn Mandarin, and live and eat on-site in separate dormitories and a canteen.

The Hubei Daily report described the program as a labour recruitment program, designed to fill staff shortages in the factory while addressing poverty in Xinjiang – claims that are disputed by analysts as propaganda.

The company confirmed to the Guardian it exported supplies to Australia, and that Uighur people were part of its workforce under the government’s policy “supporting Xinjiang development”.

“We need to develop the western region, let the people there be employed, and improve their living standards, and help them get rich,” the company employee said.

“We have dedicated dormitories, chefs, and teachers for them … Because their language is different from here, there are teachers. Every employee will have a teacher to supervise them, talk to them, and arrange work.”

It declined to comment further when asked about claims of forced labour.

The Guardian has established that at least two Australian companies have purchased stocks of surgical masks from Hubei Haixin for local distribution.

Both said they were unaware of the use of Uighur labour, and have expressed concern about the allegations.

One of the companies, MCG Electronics, says Hubei Haixin has shipped roughly 200,000 masks to various distributors in Australia since the beginning of the pandemic.

“Thank you for sharing this update with us because we were totally unaware of such involvement,” a company spokesman said in an emailed response to questions from the Guardian.

An investigation by the New York Times this week, which identified PPE manufacturers in China using Uighur labour and exporting to the US, drew sharp rebuke from Chinese state media, which accused it of “hyping forced labour fallacies”.

“This aims to slander China’s poverty alleviation policies in Xinjiang as transferring surplus labor in Xinjiang is an important way to increase local residents’ incomes,” said the report in hawkish state mouthpiece, the Global Times.

Peter Irwin, the senior program officer at US-based group the Uyghur Human Rights Project, said China’s forced labour program was often labelled “poverty alleviation” but was “inextricably linked to broader, coercive policies intended to erase the Uighur identity itself”.

“Mass detention for the purpose of ‘re-educating’ the population is its most obvious manifestation, but it filters down into nearly every aspect of Uighur life,” Irwin said.

“The forced labour programs were developed alongside these policies as a means of extracting labour from Uighurs while at the same time forcing them to attend indoctrination classes.”

It is extremely difficult for consumers to work out whether the masks they are buying might be used by Uighur labour. It requires working out which Australian distributor has supplied a particular shop, then tracing the distributor’s supply chain back to a Chinese factory, and determining whether that factory has been named in a report on forced labour.

Experts also say western companies face extreme difficulty in auditing supply chains in China due to the secrecy and sensitivity surrounding its treatment of Uighurs.

The ASPI analyst Vicky Xu, who investigated the Uighur labour program with research assistant Stephanie Zhang, said it was becoming “absolutely impossible” for auditors to conduct normal human rights checks on factories in China, making due diligence extremely difficult.

“What companies in Australia can do is conduct as much soft due diligence as possible,” she said. “If a thinktank like us can figure out what a company’s supply chain looks like, I think Australian importers will be able to conduct a desktop-based investigation, look into their own supply chains, ask questions, and try as much as possible to avoid factories and brands that use Uighur labour, especially potential forced labour.”

The second Australian company, My Queen Pty Ltd, was also unaware of the allegations of Uighur labour use, and only purchased one batch of masks from Hubei Haixin. The company has no plans for further purchases, and says the small amount of masks it imported were mainly kept for internal staff use.

Xu said Uighur workers were generally kept under heavy surveillance, including through an app on their phone, WeChat groups, and by police officers and factory managers.

She said in 2020 China, “you don’t need a whip, you don’t need brutal force, you just need all these surveillance measures in place and no one will dare oppose”.

“When they get shipped out, according to multiple documents including state media and government documents, every 50 workers have one minder, and sometimes there are Xinjiang police officers who travel with them,” Xu told the Guardian.

“They arrive at the factory, they work, and outside of work hours they have to study Mandarin, they have to take these political classes that are basically indoctrination sessions. They live in segregated dormitories and eat at segregated canteens.”

“We couldn’t see and visit every factory that we looked into, but the factories that we did visit … there are barbed wire fences around the factory, there are watchtowers, there is a police station inside the factory compound, there are AI cameras.”

Xu did not visit the Hubei Haixin factory.

The lack of transparency in supply chains makes it extraordinarily difficult for companies to be checked for the use of Uighur labour, but that shouldn’t let them off the hook, Irwin said.

“We all know that the [Chinese] supply chains are designed murky to avoid complicity in these very issues,” he said.

“Australian companies in this case need to take a hard look at their supply chains and determine whether it is even possible to understand if they are sourcing from factories implicated in forced labour. If they are doing so, they are implicated in the much broader abuses.”

China’s PPE supply has been contentious throughout the pandemic.

When the outbreak began in China, officials, expats and companies rushed to buy up medical equipment around the world and ship it home. When the burden of infection shifted to the rest of the world, China increased production and began shipping planeloads of equipment to virus-hit countries as “aid”, and to others as commercial supply.

The ramp up in production and supply was dubbed “face mask diplomacy”, and conflated with international politics and reputation-building more than with altruism. Chinese authorities were forced to repeatedly alter export requirements after shipments of faulty goods.

As hostilities deepened between Beijing and western powers including the US, UK and EU, “aid” shipments were concentrated towards African and South American nations, and previous recipients of Belt and Road investment.

In recent months China’s treatment of Uighurs and other Muslim minorities in Xinjiang, as well as its growing aggression in Hong Kong and the South China Sea, has sparked international sanctions and seizures of tonnes of goods believed to be associated with forced labour.

No comments:

Post a Comment