Chinatown Businesses Face a Particularly Brutal Winter

Yelp data shows that historic Chinatowns in several U.S. cities been enduring an economic downturn longer and more severe than in surrounding metros.

Weeks before the first reported U.S. case of Covid-19, the future pandemic was already inflicting economic damage in the Chinatowns of several U.S. cities. During what should have been the busiest time of the year in these Asian-American enclaves, business was down.

In January 2020, dim sum parlors and banquet halls in Lower Manhattan’s Chinatown noticed a drop in reservations. A conspicuously thin crowd gathered to watch San Francisco’s Lunar New Year parade on Feb. 8. At a grocery store in Houston’s Chinatown, sales fell overnight.

The downturn was attributed to xenophobic fears of the novel coronavirus that was then racing through the Chinese city of Wuhan. It became a collapse in March, as public health restrictions shuttered restaurants, salons and retailers in many U.S. cities. By summer, even as some businesses partially recovered with relaxed public health restrictions and pandemic fatigue, the streets and shops of Chinatowns remained much quieter than those in surrounding metropolitan areas.

Now, as the country copes with a new surge of infections and braces for a second year of pandemic misery, business owners and community leaders fear that these historic entry points for Chinese and other Asian immigrants may never return to their pre-pandemic stature. Instead, the economic pain that Chinatowns are now enduring could be a glimpse of broader devastation to come.

“What distinguishes Chinatown businesses is that they’ve been facing financial and fiscal problems for a much longer time, with deeper cuts to revenues,” said Paul Ong, an economist and urban planner at UCLA who directs its Center for Neighborhood Knowledge. “If we see that they aren’t coming back at a meaningful level over the next year, that would tell us a lot about businesses in other communities. It’s that early experience that makes them a potential leading indicator of other changes that are lagging behind.”

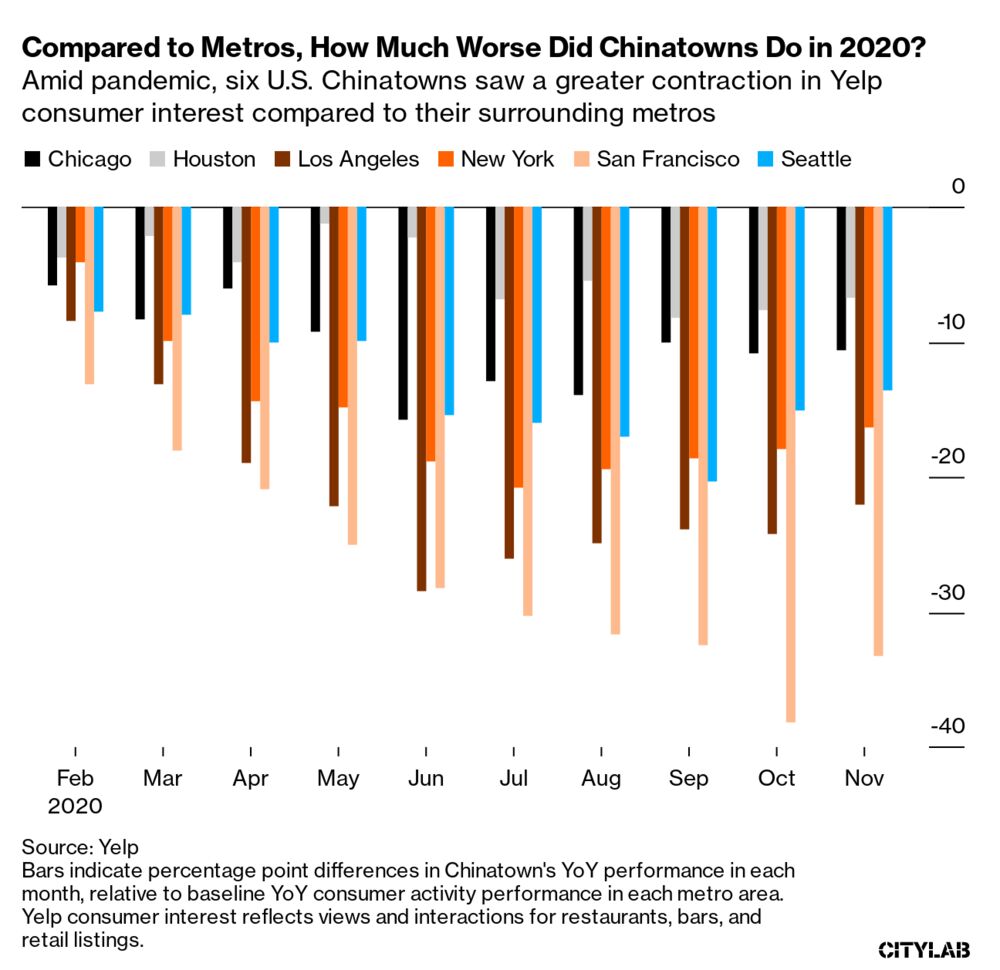

Data from review website Yelp Inc. is a proxy for how that story played out in the Chinatowns of New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, Houston, and Chicago over the past 10 months. The business search platform measures what it calls “consumer interest” by capturing views of listings and posts of photos and reviews.

From February through November, consumer interest levels for restaurants, bars, and retailers in zip codes associated with those six Chinatowns trailed behind those of their greater metropolitan areas. This was true even after public health restrictions hurt urban economies across the board, and even after partial recoveries began. The chart below shows how, as measured in the percentage point difference between year-over-year monthly growth of consumer interest in Chinatowns and that of metro areas.

There were variations between the places measured. Economic gaps between Chinatown zip codes and surrounding metro areas were widest in San Francisco, Los Angeles and New York City. Houston had the narrowest, perhaps a reflection of its Chinatown being younger than the others and located in a more residential area, as well as Texas’s relatively loose public health restrictions on restaurant and business activity.

Several interviewees said that Chinatowns suffered more deeply than the surrounding urban economies in part because the xenophobia that kept customers away early on has only persisted. “I was dealing with community members who were fearing they were going to be attacked,” said Debbie Chen, an immigration attorney, activist and co-owner of Shabu House, a restaurant in Houston’s Chinatown. “Things that make you really wonder, is this truly America?”

Yet Chinatowns were uniquely impacted in other ways. Mass restaurant closures may have hit especially hard in these neighborhoods, where dining is a centerpiece of local economies. Many are located in downtown areas — San Francisco’s Chinatown, for example, is adjacent to the Financial District — that became “ghost towns” with the disappearance of office workers. And several depend heavily on tourism, a sector that also collapsed this year.

“All of the other tourist areas — Union Square, Fisherman’s Wharf — it’s the same, with hardly anyone around,” said Eva Lee, who runs the Chinatown Merchants Association in San Francisco.

The loss of business hurt residents as well as businesses in these communities. Sissy Trinh, the executive director of the Southeast Asian Community Alliance, a Los Angeles advocacy group based in Chinatown, said that government agencies have failed to recognize the depth of need in that community, one of the city’s poorest. Officials failed to translate public health materials into Chinese, she said, and state guidelines wound up disqualifying the poorest seniors from a food assistance program.

Trinh attributed some of these oversights to the “model minority” myth, or the racist belief that Asians outperform other groups in socioeconomic terms. At the same time, many of the issues that residents of Chinatown deal with are the same as in other marginalized racial and ethnic communities.

“It’s a microcosm of what’s happening to low-income communities nationwide,” Trinh said.

Some Chinatowns also faced long-term economic challenges that predated the pandemic, including a decades-long decline in garment manufacturing, an industry that once employed tens of thousands of low-wage workers, Ong said. Changes in immigration laws and policies favoring wealthier, more highly educated immigrants also contributed to shrinking ethnic economies, while migration to suburban areas like the San Gabriel Valley of Los Angeles has further depleted historic urban enclaves.

Many residents have also felt the pressures of rising housing costs in recent years, given their proximity to gentrifying downtown areas. In some, homeless populations were on the rise: In a January 2020 citywide count, 59 Asian people were reported as homeless in the council district containing Los Angeles’ historic Chinatown, up from 6 in 2019.

And that was before the pandemic. “I’m terrified about what this upcoming count will show,” said Trinh. “People are getting further and further behind on rent, landlords are getting increasingly aggressive about eviction, because Chinatown is gentrifying. There are targets on our residents’ backs.”

Some Chinatowns have benefited from targeted assistance campaigns by community groups, such as a $1.5 million emergency fund for small business loans led by the Renaissance Economic Development Corporation in New York City. Yet absent a wave of government assistance to owners, renters and workers in these communities, interviewees said they expect these trends to accelerate as a result of the pandemic.

Specific trajectories are hard to predict, especially since it’s still unknown whether downtown areas will remain desirable from a real-estate standpoint, Ong said. If they do, longtime Chinatown residents and business owners could be pushed out and replaced by newcomers. If they don’t, storefronts may empty out, and stay empty — and homeless populations may grow.

While a vaccine promises to bring relief to the U.S. in 2021, the effects of the Covid-19 recession are expected to outlast the end of the pandemic itself. With a new president entering office and hope of second pandemic relief stimulus, Ong said, the potential loss of these historic communities ought to be reckoned with and addressed before it’s too late. Their sped-up decline may be a leading indicator of what’s to come in the broader economy, Ong said, but so could their recovery.

“That’s one of the reasons it’s important for those who are vested in future of Chinatown get engaged in the larger discussion about recovery,” he said. “If we can intervene to save these businesses and neighborhoods, that may tell us a lot about what we need to do to help businesses and workers beyond Chinatown.”

States, Cities Want More Time to Spend Covid Aid

States and municipalities are calling for an extension of a year-end deadline to spend federal pandemic aid as demand surges for government assistance amid the worsening pandemic.

As part of the Cares Act in March, Congress sent $150 billion to states, large cities and counties for unbudgeted costs related to the pandemic. Those funds must be used for expenses incurred by Dec. 30, according to the Treasury Department. But state and local officials are lobbying for an extension to give government agencies and nonprofits that received the money more time to spend it, a step they say is crucial with the outlook for additional aid uncertain.

An extension would ease pressure on organizations like the Miami Valley Community Action Partnership, a Dayton, Ohio-based non-profit, which received 76 applications for assistance in a single morning this week. It’s already paid out close to $6 million in rental aid in 2020, compared with $138,000 in 2019, and its 130-member staff is working nonstop to process claims and dole out the group’s share of Ohio’s federal stimulus aid in the next four weeks, said CEO Lisa Stempler.

“We’re really terrified,” Stempler said, adding that the Miami Valley partnership saw its budget more than double to $22 million this year thanks to the Cares Act. “We know we’re going to be looking at an eviction crisis if this money is not extended. That’s our biggest fear. Somebody sitting in our queue waiting for assistance and they get evicted before we can do anything to help them.”

A coalition of attorneys general from 43 states, Washington, D.C. and five U.S. territories, sent a letter this week to congressional leaders urging an extension of the deadline to at least Dec. 31, 2021. Setting up standards and procedures to distribute the money takes time and the need for such aid has only grown, the attorneys said. When the deadline was set in March, the outlook for the pandemic looked much different than it does today, the attorneys argued.

“The pandemic will continue to challenge communities well beyond December 30, 2020 — a deadline that now seems unreasonable,” according to the letter dated Nov. 30 and signed by Democratic and Republican attorneys general across the country. The National Association of Attorneys General, which sent the letter, said it hadn’t yet received a response from congressional leadership.

The request comes as a bipartisan group of lawmakers from the House and Senate proposed a $908 billion package this week. State and local aid has been a major point of contention between Republicans and Democrats during the negotiations over Covid-19 relief.

A full accounting of how much of the state and local aid has been spent won’t be publicly available until January, according to a newly created U.S. Department of Treasury tracker. Despite the bill’s March passage, the U.S. Department of Treasury did not clarify guidelines on spending until late April, and smaller governments did not receive direct payments at all, leaving them waiting for pass-through allocations from states.

In Alaska, $1.04 billion of the total $1.25 billion the state received from the Cares Act has been distributed, but not all of those funds have been spent, according to Neil Steininger, director of the state’s Office of Management and Budget.

Grant programs like rental assistance, food assistance and others had to be created to give out some of the funds, and the smaller municipalities facing budget pressure couldn’t plan programs until the funds were received from the state, said Nils Andreassen, the executive director of the Alaska Municipal League.

“The pressure is on for sure,” Andreassen said. “Everybody would have liked to have more time. An extra six or 12 months would’ve lent itself to a more measured approach.”

In Iowa, about $325 million of the state’s $1.25 billion Cares Act allocation hasn’t been spent yet, though some of those funds have been allocated to agencies, according to a summary provided by Iowa Attorney General Tom Miller’s office. Another $75 million remains unallocated. Miller signed the letter requesting an extension. A spokesperson for Governor Kim Reynolds, who has called for more aid, said the funds will be spent by the deadline.

Like Iowa, municipalities that still have funds to use will find a way to spend the funds before the deadline, said Emily Swenson Brock, director of the federal liaison center at the Government Finance Officers Association.

The need for aid has not abated. The U.S. posted an all-time daily high in reported Covid-19 deaths of 2,836 on Wednesday, according to Johns Hopkins University. As cases climb, governors and mayors are enacting restrictions and economic shutdowns again. State and local governments’ finances face $480 billion to $620 billion in shortfalls through fiscal 2022, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

But federal stimulus money from the Cares Act can’t be used for budget holes, another reason that governors and local officials are asking Congress for more aid in 2021.

Wisconsin will need at least $466 million in the first quarter of 2021 to pay for ongoing expenses related to the Covid-19 pandemic, money the state doesn’t have, Governor Tony Evers said Thursday.

Evers, a Democrat, sent a letter Thursday to his state’s congressional delegation, urging its members to push for an additional federal Covid-19 relief bill. Evers said his state simply doesn’t have the money to pay for the ongoing disruptions to the state’s economy caused by the pandemic after Dec. 31.

Wisconsin received $2.26 billion in Cares Act funds, which it has used for grants to farmers, small businesses and for rental and mortgage assistance. Additional Cares Act money will be spent on grants to 663 hospitality operators, Evers said.

“Having aid that helps states and localities fight the virus end when the virus is spreading is a terrible idea,” said Michael Leachman, vice president for state fiscal policy at the CBPP. “It’s kind of a no-brainer to help states and localities avoid the additional layoffs and cuts that would make that double dip recession more likely.”

No comments:

Post a Comment