Quants Need an X Factor to Avoid Black Swans

The value disaster has challenged a popular style of investing.

To get John Authers' newsletter delivered directly to your inbox, sign up here.

Not-So-Smart Beta

Not so long ago, Factorland was the only place to be in investment world. Factor-investing — using quantitative screens to buy stocks that look good according to attributes that tend to beat the market over the long term — has seen an explosion of academic interest, along with intense commercial attempts to exploit it. “Smart beta,” offering exchange-traded funds that tracked indexes built to exploit specific factors — such as value, momentum, quality or low-volatility — gained huge inflows. Andrew Ang, who heads factor investing for BlackRock Inc., even suggested that they should be treated like nutrients in food: whenever we made an investment, we were in fact feasting off the various factors we bought with it.

On to this was added the notion of “multi-factor” investing. The idea was that the active ingredients could enable investors to build a better mousetrap. Put several different factors together in a portfolio, and those doing well would outweigh any doing badly, and lead over time to performance that steadily and predictably beat the index. The counter-argument was that this was just an unnecessarily expensive way to smoosh together a group of investment styles that would cancel each other out and leave investors with the market return that they could have had much more cheaply.

The latter, skeptical group have been in the ascendancy this year as smart-beta hasn’t looked quite so smart. The Covid-19 market shock inflicted serious damage on many quantitative factor investors. Now the question is whether this was a one-off, or whether, as some claim, the whole concept of factor investing is now broken.

BNP Paribas SA is making a spirited attempt to show that factor-investing remains viable. The problem this year was restricted to the value factor (buying stocks that look cheap relative to their fundamentals), and, to a lesser extent, size (buying smaller-cap stocks).

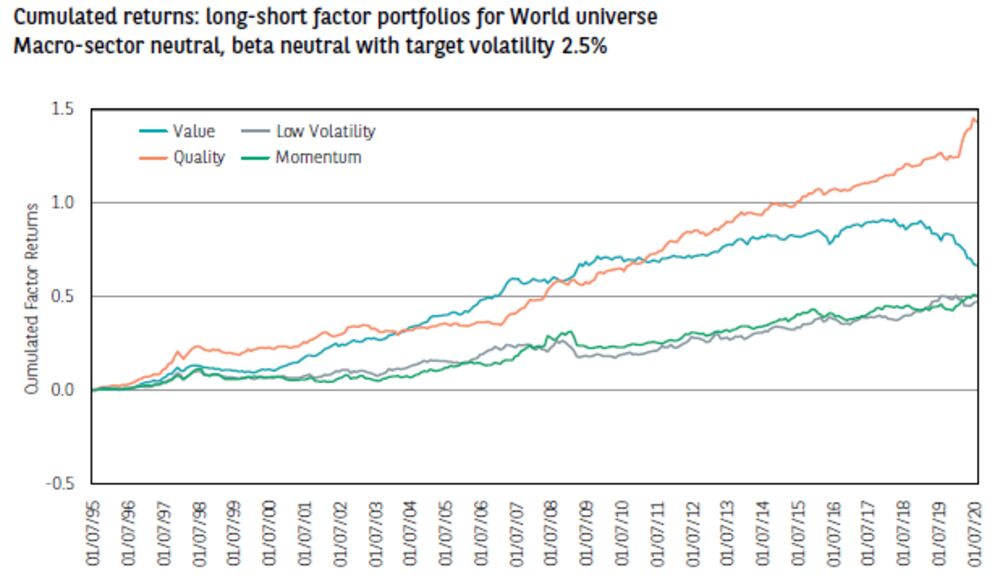

The following chart shows BNP’s estimates of pure factor returns over the last quarter-century. They are shown via the performance of the best stocks judged by a factor, compared to the worst (a “long-short basis,” in the jargon). They are sector-neutral, so that if an entire sector looks cheap the value factor cannot be filled with companies from that group, while the quants at BNP also controlled for “beta,” or sensitivity to the market.

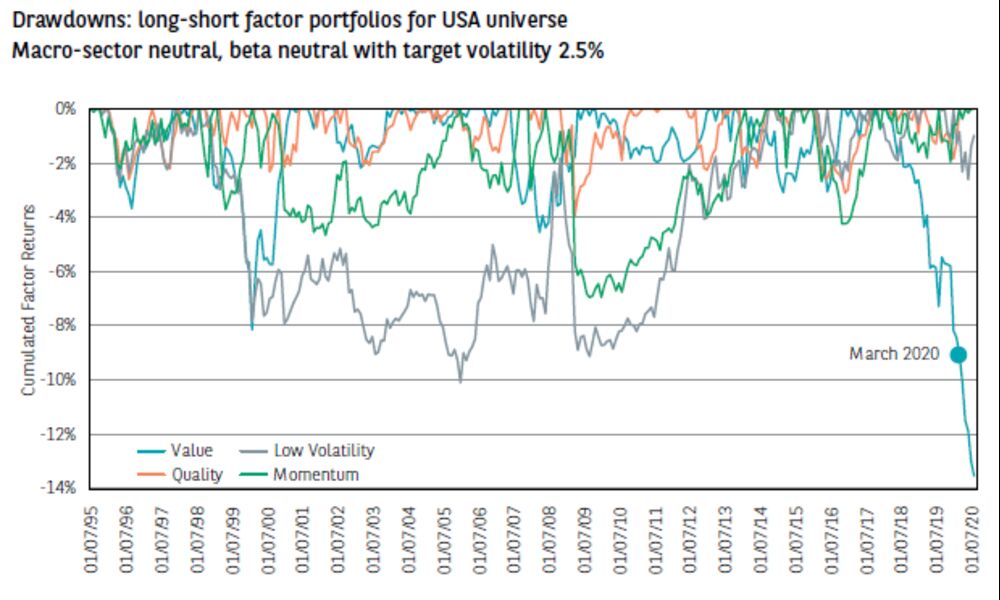

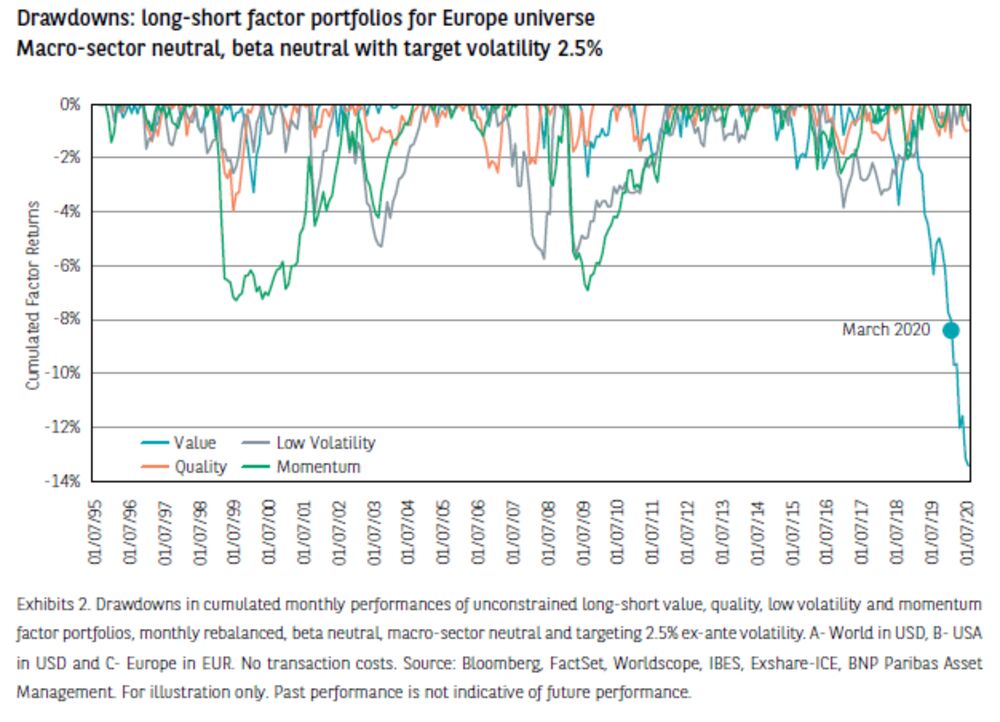

The following chart shows all the drawdowns, or percentage falls, that each of the four main factors followed by BNP have suffered following a high, going back to 1995. Looked at this way, no factor until this year had ever suffered a drawdown as bad as 10%. Value was already suffering every bit as badly as it did during the dot-com boom when the pandemic prompted much of the economy to shut down in March. What happened then, given the previous history of factor performance, can truly be called a black swan:

This cannot be dismissed as an American phenomenon driven by the incredible performance of the FANG internet plays. Value’s underperformance in Europe over the last year has been identical to the U.S.:

Note that none of the other factors have suffered significant drawdowns. The dreadful performance of multi-factor funds was more or less entirely a function of a biblically bad year for value. When the economy locks down for a pandemic, it turns out, companies that the market was already reluctant to hold are the worst place to be. There may never be another lockdown like the one of 2020. So maybe it’s fair to hope that there will never be another value drawdown like this.

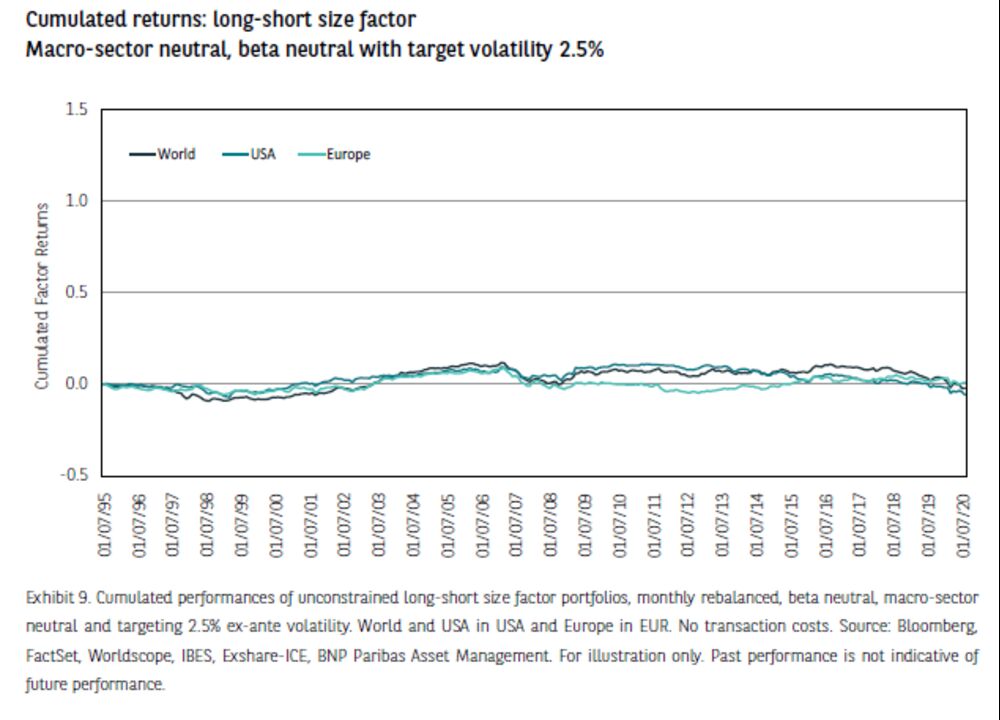

The other culprit is the size factor. Over the last quarter-century, buying small-caps while shorting large-caps was barely worth the effort. It suffered reverses during the dot-com bubble and again during the global financial crisis. Academics have recently questioned whether there ever was a viable smaller company effect — and the strategy is again failing to make money. The following chart from BNP Paribas shows the results of betting on smaller companies and against larger ones across a range of geographies, again screening out the overall effect of the market and of individual economic sectors. Those betting on small-caps this year would likely have been hurt:

The argument in favor of sticking with multi-factor investing is that it still isn’t doing all that badly, even after the value disaster. The following BNP Paribas chart shows the excess returns made by the four factors on a long-short basis across the world over the last 25 years. All of them rose. The approach wouldn’t have beaten the market this year thanks to the value slump, but it would still have come close because another factor — quality — picked up the reins:

This year, as quant managers tend to rely on value more than other factors, and many were positioned in March for what already seemed to be a way-overdue return to form for value, it is a fair bet that many have done worse than these numbers imply. Any managers who didn’t control for economic sectors will have loaded themselves with lots of financial stocks (which have shown up as buys on value screens for years), making things worse.

But does this mean that the notion of factor investing should be rejected? Perhaps not. In BNP Paribas Asset Management’s report, Equity Factor Investing: Historical Perspective of Recent Performance, Raul Leote de Carvalho, deputy head of the quant investment group, makes the case with appeals to common sense rather than numbers:

There is the strong financial rationale of investing in the cheaper (value) and less risky stocks (low risk) that are outperforming (momentum) and that have the strongest fundamentals when it comes to profitability and quality of management (quality). This is not merely sensible; it has been backed by academics and by empirical evidence for decades, and despite the many changes we have witnessed throughout time in terms of market regimes, in the way stocks are traded, in how technology is used by markets participants and even changes in the actual investors themselves.

Second, it removes human emotion and biases from the equation. In fact, human behavioural biases have been put forward as a key explanation of the long-term performance in factor investing.

I think they have come up with enough reasons to explain the value disaster this year, and also to explain why it should be treated as a “black swan” or a “one-off.” So despite this year’s horror show, the world is still safe for multi-factor investing.

Game Theory: Year’s End Edition

With only two full working weeks left in this benighted year, there is still plenty of game theory to play out. Currency markets seem uninterested. I’m not sure they’re right.

In the U.S., there is the continuing attempt by the president to challenge the results of the election. The courts don’t seem to be taking this seriously, which explains why the markets aren’t either — record stock indexes, falling volatility, and a move away from havens wouldn’t happen if the world’s largest economy was thought to be in a constitutional crisis. Meanwhile, those same market behaviors imply at least some confidence that there will be a deal on extra support for people affected by the pandemic, which would sharply reduce the risk of a further economic downturn.

For the time being, there seems to be a belief that bad news is good, because it increases the chance that Congressional leaders cave and make a deal (fiscal stimulus), and that the Federal Reserve caves further and announces some kind of additional balance sheet expansion (monetary stimulus). Beyond the game theory in Congress, there is also a game between the bond market and the Fed. If the 10-year yield goes through 1% this week, will that be enough to force the Fed to do something next week?

Before the Fed meets, however, we should see the result of an epic “chicken game” in Europe. The phrase comes from the James Dean movie where two contestants drive their cars fast toward a cliff. The winner is the one to swerve last — but if they try too hard to win, there is a risk of disaster. Think of this as a chicken game on the white cliffs of Dover.

The U.K. is at the time of writing trying to negotiate a new trade deal with the EU, to replace the rules that will cease to bind it on Jan. 1. The game theory had seemed clear. This is a difficult situation so a “skinny” deal with many issues still to be resolved is likely. Both sides would be harmed by “no deal,” and the U.K. has more to lose than the EU, so a compromise somewhat more to the EU’s liking was probable. Covid-19 increases the arguments for thrashing out a weak compromise so as to concentrate on public health.

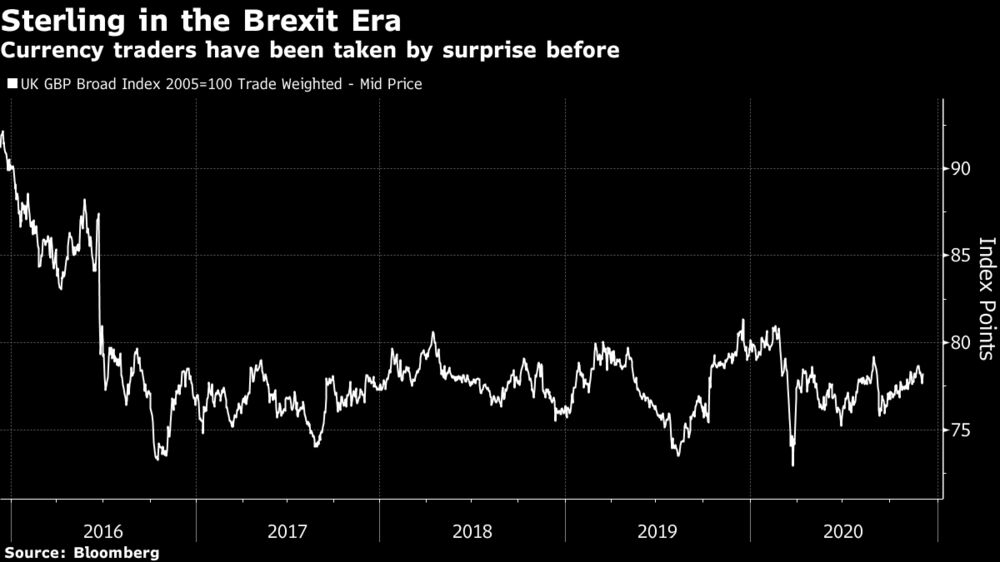

Judging by the pound’s performance, there is little danger of no deal. Traders have been bidding up sterling steadily. On a broad trade-weighted basis (dominated by the euro), the pound has been enjoying a slow and steady appreciation as the U.K. and EU both try to tell the world that they are prepared to walk away:

If there was a real risk of a crash in the negotiations, we might expect the pound to be closing on its post-Brexit lows. Against that, a historic fall on referendum night in June 2016 shows that the currency market was blindsided that time. Is it being blindsided again?

Here is the case that it might be. The talks are agonizingly slow. The issue of a “level playing field” between the U.K. and EU, putting limits on Britain’s ability to boost its competitiveness (via subsidies or light regulations) is dangerously difficult to resolve. For the British, it is about “taking back control” and sovereignty, while for the EU it is about stopping the U.K. from enjoying the benefits of the EU club without paying membership fees. If a format for dealing with this still isn’t evident, that is a problem.

Then there is the effect that Covid-19 has had on Boris Johnson. A year ago, the U.K. prime minister had just won a strong parliamentary majority. But his Covid policy has aggravated opposition, much of it from the same Conservative politicians who voted down early attempts at compromise over Brexit. There is, again, room to his political right in domestic politics, and some risk that he might not be able to win parliamentary confirmation for a deal. Similarly, EU politicians don’t want to show generosity to the British when many countries that are still members think they deserve more.

The effects of a no-deal exit would be bad on both sides of the English Channel. But for Johnson and the EU, it is conceivable that the conditions caused by Covid might make that seem a conscionable price to pay. For a great discussion of the game theory, try this podcast from Talking Politics, recorded just before the final round of talks got under way.

Sterling may be a little too relaxed about this. If the politicians decide to drive off the cliff again, there would be time for one last dose of nasty volatility before the year ends.

No comments:

Post a Comment