China’s Gloomy Drumbeatby John Authers |

The drumbeat of major news headlines from China on an almost daily basis seems all but to spell doom for the world’s second-largest economy. After decades of growth far in excess of anything in the developed world, the picture looks troubled. Rebecca Choong Wilkins and Colum Murphy put it succinctly in this Big Take piece: “The $18 trillion economy is decelerating, consumers are downbeat, exports are struggling, prices are falling and more than one in five young people are out of work.”

On top of that, Country Garden Holdings Co., one of China’s biggest real estate firms — with 3,000 pending property projects — barely avoided a default, bringing some respite amid a liquidity crisis. And Zhongzhi Enterprise Group Co., one of the largest shadow banks, missed dozens of payments on several high-yield investment products, stoking contagion fears.

The Chinese currency offers a dramatic illustration of the problem. In the first decade of this century, much of the world complained (with reason) that China was keeping it artificially cheap. Years of managed appreciation followed. But now, the yuan has dropped to 7.3 to the US dollar with surprisingly little comment. This time, investors think the level is reasonable:

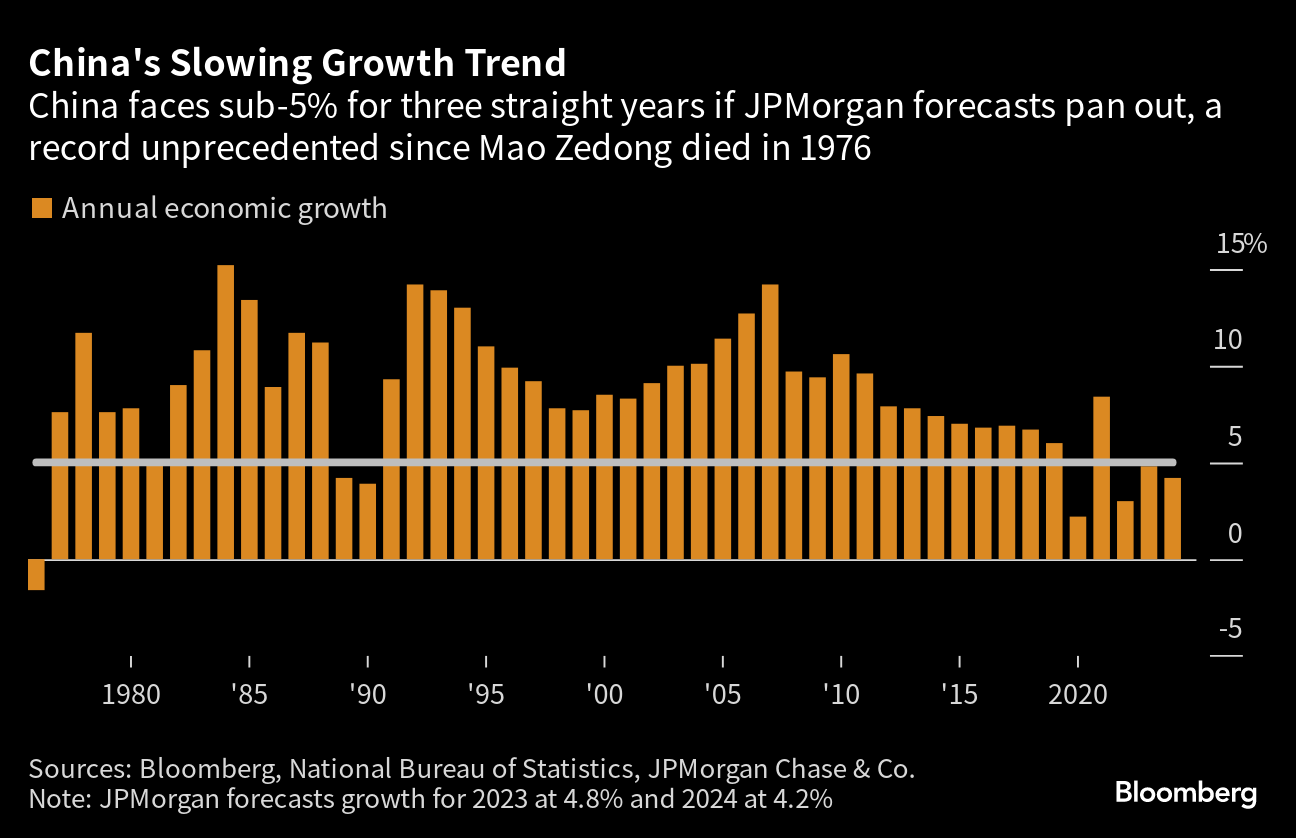

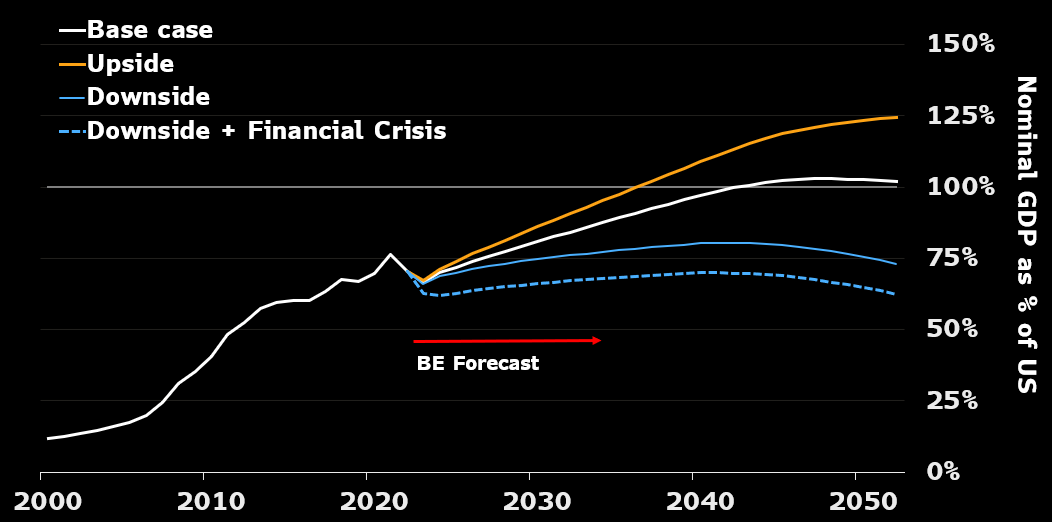

Will the fading economic momentum after a lackluster Covid-19 restart endanger China’s growth target of about 5% for this year? Perceptions of the contest with the US have turned on their head. Bloomberg Economics forecasts it will take until the mid-2040s for China’s gross domestic product to exceed that of the US — and even then, it will happen by “only a small margin” before “falling back behind.” This is a stark shift from before the pandemic, when the team expected China to take and hold pole position as early as the start of the next decade.

“China is down-shifting onto a slower growth path sooner than we expected,” Bloomberg Economics wrote in a Tuesday research note. “The post-Covid rebound has run out of steam, reflecting a deepening property slump and fading confidence in Beijing’s management of the economy. Weak confidence risks becoming entrenched — resulting in an enduring drag on growth potential.”

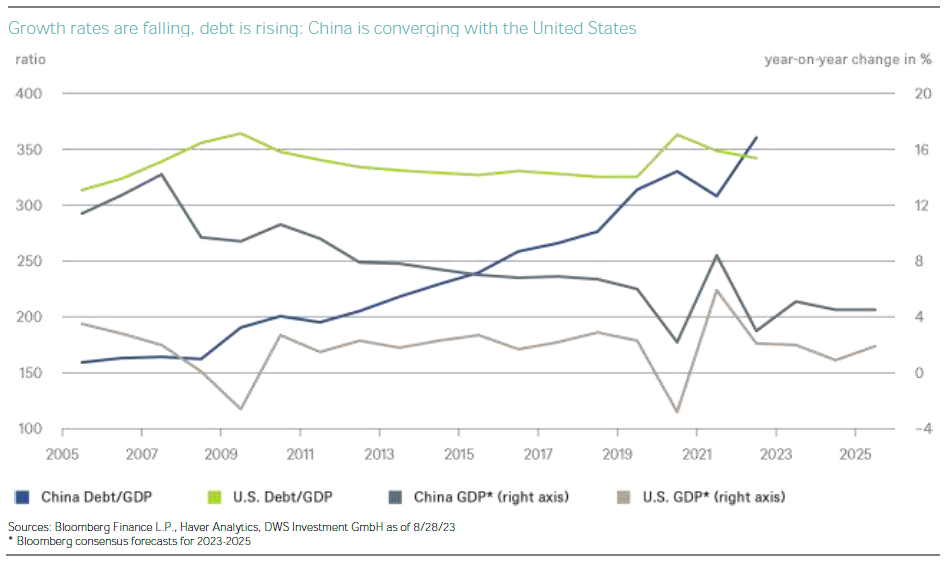

Meanwhile, China has converged with the US economy in a way it had hoped to avoid. As this chart from Björn Jesch, global chief investment officer at DWS Investment shows, China’s debt to GDP ratio has now overtaken the US, while its growth rate is also converging. The Global Financial Crisis proved to be the cue for US retrenchment, while China became the world’s borrower of last resort:

It is China’s debt, more than anything else, that is arousing concern, and dividing opinon. Diana Choyleva of Enodo Economics, a long-time China-watcher, made this scathing assessment after reviewing projections for credit losses:

The numbers are a shocker. We estimate credit losses at between 37% and 42% of GDP, up from 26%-31% last year. The Party-state faces its biggest clean-up operation in the most challenging of times. Looking at impairment rates by sector, it is noteworthy that IT is most at risk , surpassing real estate whose woes are well understood. This is not only a reflection of the fact that Xi Jinping managed to bring China's tech giants to heel, hurting their bottom line, but also a serious worry for the leadership's technology ambitions for China.

That hasn’t thwarted China from the notable coup of producing its own chip for the Huawei Mate 6 smart phone, but does demonstrate the difficulty the country’s leadership is likely to find as it tries to clamp down on the private sector while attempting to compete with US technology.

For the future, Bloomberg Economics projects growth slowing to 3.5% in 2030, 2.8% in 2040 and near 1% in 2050. Previously, they had expected those numbers to be 4.3%, 3.4% and 1.6%, respectively. Because of this, they no longer see the Asian superpower on pace to eclipse the US as the world’s biggest economy soon, as the confidence slump becomes more rooted. It still expects China to grow in the medium term, but with “drivers operating with diminished force.”

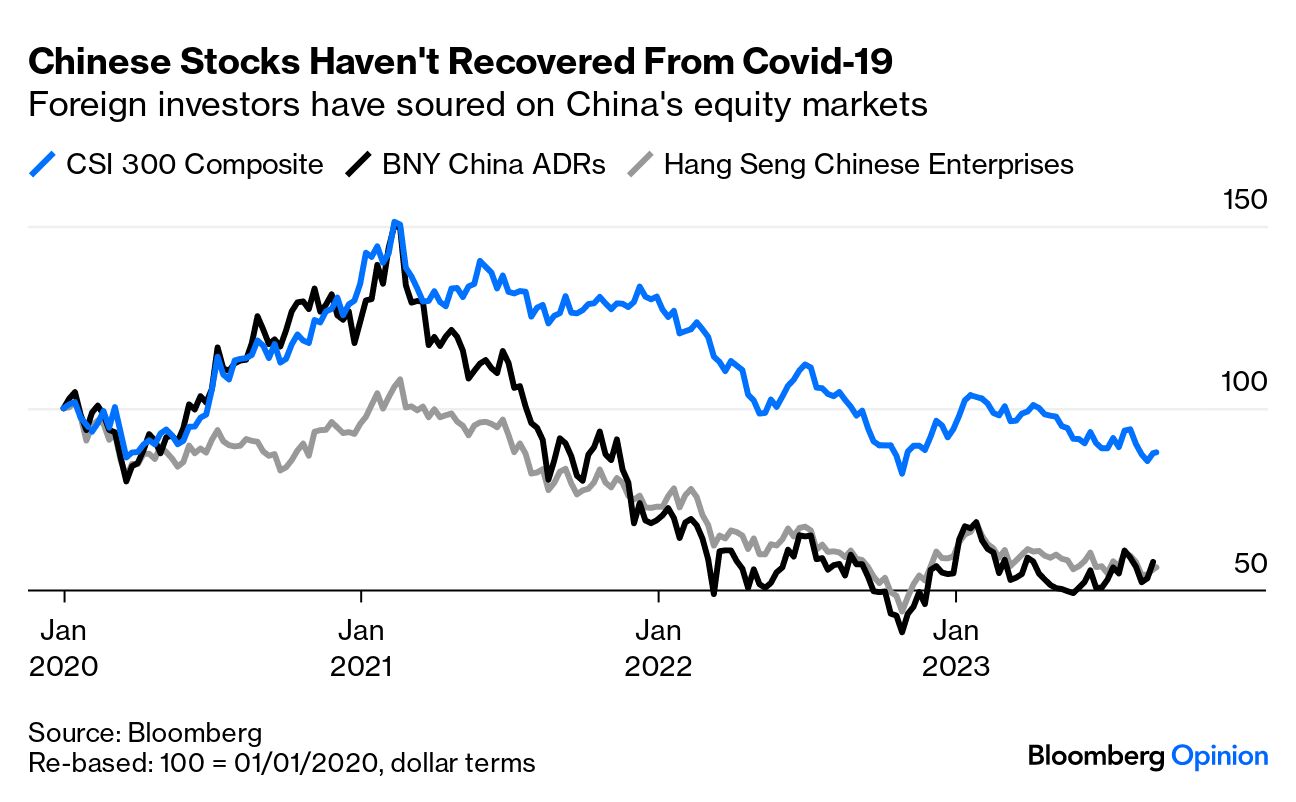

This angst has had little effect on Chinese share prices, perhaps in large part because they had already taken a serious dive in reaction to President Xi Jinping’s crackdown on the private sector, and the worsening trade relationship with the US. Those traded in the US and Hong Kong are slightly above the lows they set almost a year ago, when it appeared the Covid-Zero restrictions would go on forever. Stocks traded in mainland China, not so badly affected by the corporate sector crackdown, are approaching last year’s low:

Does China’s slowdown — whether it’s a blip or a reinforcing shift — matter elsewhere? To the International Monetary Fund, a weaker GDP trend would have an impact on almost every country. The organization had earlier forecast that the Asian nation will be the top contributor to global growth over the next five years.

But a few on Wall Street hold that some will suffer less than others. Back in 2015, an unscheduled Chinese devaluation, followed by economic wobbles, were enough to persuade Janet Yellen, then chairwoman of the Federal Reserve, to call off an interest-rate hike. That incident triggered a minor crisis across world markets. Now, in the US, China does not matter much. “There are other things more important for us to worry about than China,” said Michael Rosen, co-founder and chief investment officer at Angeles Investment. “Trade is a very small percentage of our GDP. We’re mostly a closed, self-sufficient economy.” Thus, growing Chinese worries have co-existed with a steady rise in US Treasury yields and a much stronger US dollar.

It is a different story in Europe, where companies derive a significant portion of their revenues from China. “European markets are sensitive to Chinese news,” Raphael Thuin, head of capital markets strategies at Tikehau Capital, said. “China is a key economic capital.” A weakening China could almost be seen as reinforcing another dose of “American exceptionalism; US stocks have led the world since the GFC, and the emerging bet on Wall Street is that this could continue.”

Something that concerns Thuin is the “Japanification” of China, a sentiment some economists have shared against the backdrop of the latest consumer price data showing deflation.

Another issue, of course, is geopolitics, which would require a column of its own. The US and the Group of Seven nations are looking to take advantage of China’s weakness to strengthen the West’s hand against an ailing geopolitical competitor.

But not all is pessimistic. Matt Miskin, co-chief investment strategist at John Hancock Investment Management, pointed out that China is initiating fiscal stimulus for its beleaguered property sector, in contrast to tighter monetary policy in the US, Europe and the UK. “There is a massive policy divergence going on globally which historically has resulted in significant currency movements, but we are seeing a risk-on move in markets that generally favors more risk-on currencies short-term.”

Thus far, Chinese authorities have resorted to a drip-feed of targeted measures instead of the hoped for single package, as was deployed during the 2008 GFC. That, it appears, is no longer an option. Instead, the currency is inexorably weakening, while the rest of the world seems almost totally unconcerned. Can this last?

No comments:

Post a Comment