This traumatizing reportage from Bloomberg illustrates what happens when a land - an entire continent, in fact - is occupied by settlers who use it almost exclusively for capitalist accumulation and egoistic enrichment.

Australia has long neglected to infuse its citizens with the patriotic devotion that is key to nationhood and indeed to the very survival of its environment.

With the onslaught of massive immigration, motivated by the same vaulting greed for capitalist accumulation, the Australian continent is on the edge of ecological catastrophe and human uninhabitability.

Investors Are Getting Rich Off a Trade That’s Sucking a Continent Dry

Share this article

On the day the trucks took away Meghan Campbell’s cows, she wept. Campbell, 23 at the time, had helped build her family’s herd of 500 dairy cattle since grade school. She ordered her first cow embryos at age 14. She’d talked to her dad about becoming the third generation to run the 800-acre dairy in Australia’s middle Murray River district.

As the last truck pulled out, one of the cows Campbell had nurtured poked her head over the tailgate and looked back. Its name was Hope.

The Campbells shut down their dairy in 2019, at the peak of Australia’s last drought. The state of New South Wales, for the second year in a row, had allocated zero irrigation water to most farmers in the state’s Murray region. To buy water on Australia’s spot market was not an option; drought had sent the average price for Murray-Darling water up 139% percent in the past year, to A$550 ($360) a megaliter. The Campbells were still paying debt from the last dry spell a decade earlier. Now, they’d need to borrow up to A$800,000 to buy water. Meghan’s dad Neil, then 63, decided it was too much. “That’s it, darling,” he told Meghan one night. “We’re out.”

There were things they could’ve done better on the farm in Blighty; purchases they didn’t need, Meghan recalls. “But we didn’t know all of a sudden all our water would be taken away from us.”

In Australia, more than any other place in the world, water has the power to make or break livelihoods. The driest inhabited continent, it has spent the past three decades building the world’s most advanced water exchange, handing significant control of one of life’s most critical natural resources to the market. The Campbells’ farm was lost partly to drought, but even more so to the well cloaked hand of capitalism.

Today, Australia’s farmers and financiers annually wheel and deal nearly 8,000 gigaliters of water—enough to supply the population of France for a year—at a value of A$4 billion. They source it from 77,000km (48,000 miles) of interconnected rivers and streams, which feed irrigation canals in four of Australia’s six states. Almost all the trading happens in southeastern Australia, in the Murray-Darling Basin, named for Australia’s two longest rivers.

For deep-pocketed financial institutions and agribusinesses, many based overseas, water trading has been a bonanza. Big investors have wielded substantial financial clout to extract more water, and more profits, at a time when the asset is increasingly precious amid climate change and rising agricultural demand. They are abetted by financial firms that provide liquidity to the exchange, connect buyers and sellers, and earn substantial returns arbitraging the water market.

In pure economic terms, the experiment has been a success. When water prices spike, as in 2019, farmers of seasonal crops like barley, rice, and vegetables are incentivized to fallow their fields and sell their water to growers of premium products, such as wine grapes, fruit and nuts. These so-called permanent crops require large, up-front investments and need prodigious watering year-round, or the trees and vines will die.

Yet Australia’s experience turning a public good into a tradeable commodity has had far-reaching consequences, some that are only now being felt as the market matures. It provides a cautionary tale for other places considering solutions to water scarcity on a warming planet. Trading water, Australians have discovered, is tantamount to transferring wealth. The results are painful for communities, many of them Indigenous, that have seen their water disappear, farm economies gutted and environments depleted.

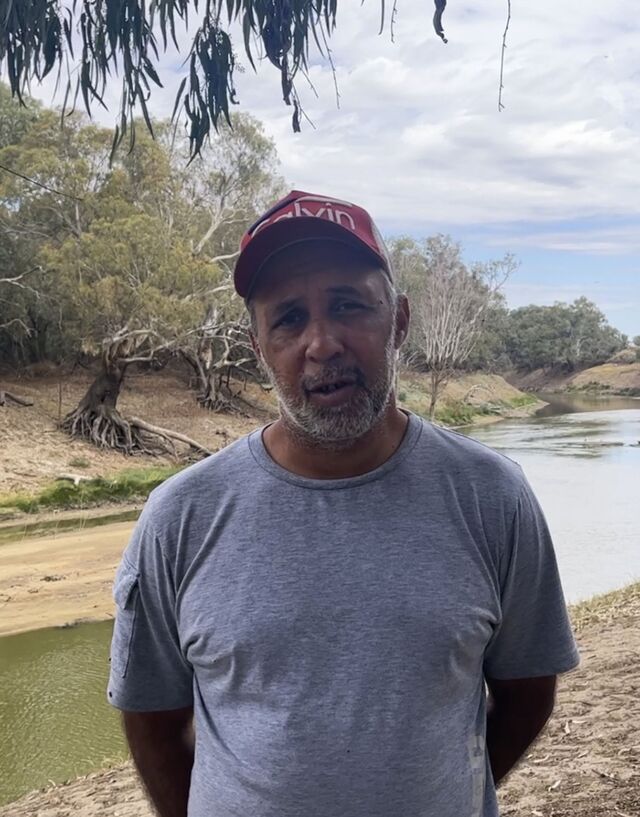

“It’s about greed and power,” says Michael Kennedy, an Aboriginal leader from Wilcannia, one of the hardest-hit towns in the Murray-Darling Basin.

Among the biggest winners are two agro-industrial complexes on either end of the Murray-Darling Basin that have been sucking water and prosperity from the middle. On the north end, along tributaries of the Darling River, cotton barons have constructed massive dikes to collect and divert water from floodplains onto their fields, coaxing bumper crops from the often bone-dry land. On the south end, wealthy investors have siphoned enough water out of the Murray River to triple voraciously thirsty, and highly lucrative, almond plantings in just 15 years. In between are the largely unregulated private irrigation companies that wield enormous amounts of water and influence, unaccountable at times to their own customers—the farmers and communities that stand to lose the most.

Almond Farming Booms at the Expense of Other Foods

Annual production of select goods in the Murray-Darling Basin

The industrial-sized squeeze on the Murray-Darling heartland has left vanishing flows for smaller farmers, animals, fish, trees and communities. In the past decade alone, communities in the lower part of New South Wales’ Murray region have sold a net 576 gigaliters of water to financiers and farms elsewhere, according to federal water data of temporary trades analyzed by Bloomberg Green. In the Northern Basin, the analysis found that just five big growers and cotton producers were granted nearly 40 percent of all floodplain diversions authorized by state regulators. The extractions have robbed the Darling of its natural flows, turning sections of the 1,500km river into little more than algal pools and puddles. Parched communities along the Basin’s interior, meanwhile, have lost their social and economic vitality.

“We feel like we’ve been sacrificed,” says Roger Knight, who runs an economic development nonprofit in the central Murray River town of Barham, which has lost its engine shop, its truck and tractor dealer, and two of three gas stations.

When Neil Campbell called it quits, he knew there was water for sale behind the dams near the Snowy Mountains, for a steep price. He watched water in the canals rush past his dying farm. “It pissed off a lot of farmers,” he says. “I went through mental hell.”

Yet at the time, farmers in the area had no way of knowing what was really happening. Just when many were at their most desperate, the Campbells’ own water provider, Murray Irrigation Ltd., was holding some 160 gigaliters behind the dams, enough to fill 64,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools—more than plenty to save multiple herds.

Neil’s daughter Meghan can’t help but think about her cows being hauled away—“what could have been,” as she puts it. Could that water have saved the dairy, she wonders. “It’s a bit of a kick in the guts.”

Shaped like a tree, with the trunk at the Murray’s mouth near Adelaide, the Murray-Darling Basin fans upstream toward the north and east, branching into 23 river valleys fed by dozens of smaller tributaries. The network drains a catchment of about one million square kilometers (386,000 square miles), just inland from Australia’s big cities on the southeast coast.

For generations, the basin nourished farms of all kinds—wheat, rice, dairy, canola—making the area Australia’s most reliable breadbasket. Managing irrigation was the responsibility of state governments. Drought was always a challenge—Australia has the most variable annual precipitation in the world—but the giant river basin produced ample food for a continent that today still has just 27 million people.

In the 1980s, policymakers began looking for ways to conserve water and wetlands, while also channeling scarce resources to what economists call the “highest and best use.” To achieve that, in 1983 Australia began legally severing water entitlements from land ownership. The audacious step allowed farmers to sell their water rights—temporarily or forever—without selling their land. While unfettered water sales benefited farmers who wanted to cash out some of their farm’s equity, it drove a wrenching transformation in Australia’s economy.

By the 1990s, Australia was facing worsening over-extraction in the Murray-Darling, and rapid expansion of global agricultural demand. State governments agreed to cap water withdrawals from the Basin. Overruns had to be repaid to the river in future years. Water trading expanded under the caps, while critics warned that communities would see their water disappear, and “water barons” would exploit the market.

Three decades later, a winegrower in South Australia can order five megaliters of water for her vineyard on a cellphone. The seller might be a brokerage with a dozen traders wielding algorithms that mesh data on weather forecasts, river flows and farmer debt levels. A few keystrokes later, a rice field is fallowed, and a vineyard is watered in the hot December sun.

Without the water market, Australia could never have mobilized sufficient irrigation to transform the nation’s farm output and emerge as the ninth-largest food exporter in the world. Since 1990, the value of Australia’s farm exports has grown six-fold, to a record A$78.1 billion in 2022. The value of Australian water entitlements has also climbed, rising at a compound annual rate of 7% in the past 15 years, according to water-research firm Aither Pty Ltd.

Sarah Wheeler, a University of Adelaide water economist, argues that the net social benefits of water markets outweigh any potential cost. “Allowing trade is an important tool in an era of increasing scarcity and variability,” she says.

Scarcity is also ideal for arbitrage, explained former Deutsche Bank executive Ed Peter, chairman and co-founder of Duxton Capital (Australia) Pty Ltd., which oversees A$1.25 billion of water and farm assets. “We’ve got a declining pool of water, and on the other side of this, we’ve got an increasing amount of plantings,” he told investors in a 2021 video presentation. “This is the perfect storm.”

In 2019, the same year the Campbells’ dairy closed, Duxton’s water-trading unit, Duxton Water Ltd., earned A$24.7 million, up nearly 60% from the year before. Almost all profits came from water sales. During the drought years of 2018 to 2020, Duxton Water and Duxton Dried Fruits transferred 12.5 gigaliters of water out of New South Wales to downstream users in Victoria and South Australia almond country. In an email, Peter called 2019 an “anomaly” due to the heightened demand from permanent-crop customers in the drought.

Even as water trading became a multi-billion-dollar business, it remained largely unpoliced. In a 700-page report two years ago, Australia’s main anti-trust regulator found the market was rife with opportunities for abuse. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission didn’t identify any improprieties, in part because inadequate trading data and other “information gaps” made such conduct “difficult to detect,” the ACCC concluded. But the agency warned that “scant rules” governing conflicts of interest, market manipulation, and other unfair conduct left the water market “mostly unregulated.”

The result is a race to profit from the nation’s water scarcity.

Australia’s cotton country lies hundreds of kilometers north of Sydney. Fluffy white strands of cotton litter the edges of the region’s flat, empty roads. Emus scratch around the dry scrub. The most prominent features are man-made: great walls of earth that rise up from the pancake landscape.

The dirt barriers, wide enough for a pickup truck, conceal everything behind them. But viewed from a tiny Beechcraft Baron plane 2,000 feet in the air, the purpose and scale become clear. They form the banks of hundreds of water reservoirs carved into the earth, one after another, like giant lakes queuing on the horizon.

On-Farm Water Storage Has Exploded

Storage volume in gigaliters

Close to 2,000 of these water storages cover an estimated 43,000 hectares of northern New South Wales. That’s an area almost as big as Lake Tahoe, the enormous mountain lake that straddles California and Nevada.

For the farmers who built the reservoirs over the past half-century, the practice known as “floodplain harvesting” has ensured a bountiful supply of water in a nation that has anything but. When it rains, instead of water pooling in the natural low-lying floodplains, and gradually seeping into the rivers, it is “harvested” or trapped by these man-made storages and then used to irrigate their vast cotton fields. The practice helped quadruple the country’s cotton output since 1990.

But downstream, the effects have been ruinous. The structures have in effect allowed the cotton industry to corner the region’s water, robbing smaller farmers and communities of the lifeblood that would otherwise flow their way, while choking the ecosystems of smaller rivers and streams. Three of four harvested tributaries on the Darling and Barwon rivers have lost more than 55% of their flow in the past 20 years; the fourth has lost more than 40%, according to a recent presentation by water economist R. Quentin Grafton of Australian National University. He and his colleagues calculate that half the decline was due solely to water extractions, primarily from floodplain harvesting, not weather.

Rivers Around the Murray-Darling Basin Dry Up

Water flow in gigaliters

For years, floodplain harvesting was allowed to explode. In 2018, pushed by public outrage amid the drought, the government of New South Wales got serious about regulation. But rather than setting simple limits on how much reservoir water could be collected, it used opaque methods to calculate extraction allowances.

Instead of curbing the amount of water that farmers can harvest from the floodplains, the cotton-friendly process had the opposite effect of allowing more. So far, the state has authorized 256 gigaliters of annual floodwater extractions in the Barwon River and three regulated tributaries of the Darling. That’s 37% more than the government estimated farmers were already taking in a typical year, according to Bloomberg Green’s analysis of public documents. Two big growers received more than a quarter of the floodplain allocations. Institutional investors received nearly one-fifth.

Floodplain Harvesting Favors Two Big Growers

Share of floodwater allocations in the Northern Basin

The biggest beneficiary was Australian Food & Fibre, the local joint-venture partner of Canada’s Public Sector Pension Investment Board, which is the C$243.7 billion ($185 billion) retirement fund of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and other security services. Since 2018, the PSP-AFF joint venture has amassed nearly 50,000 hectares of cotton land and is now Australia’s top cotton producer. Its farms were granted licenses to intercept 39 gigaliters of Darling headwaters, or 14% of all authorized floodplain extractions. That’s enough water to supply all of New York City for about 10 days.

The state also threw in a sweetener. If growers can’t harvest floodwater due to insufficient rainfall, they can carry over any unused portion of their allocation for up to five years. At one farm near the town of Bourke, PSP-AFF is licensed to capture nearly 16 gigaliters of floodwater a year. With the additional bonus, the PSP-AFF farm’s potential annual diversion is bumped up to nearly 80 gigaliters after a long dry spell.

A spokesperson for AFF and PSP in Australia said AFF supports the licensing program but “has not sourced any water from floodplain harvesting in recent years.”

The recipient of the second-largest floodplain licenses was the extended family of Jane and Peter Harris, a well-known farming dynasty. Court filings and government inquiries show that by 2020, Jane and Peter Harris had amassed some 76,000 hectares of land and sizable water entitlements in Australia.

Cotton Growers Amass Floodplain Licenses Across the Northern Basin

Licensed addresses belonging to the two biggest beneficiaries

The floodplains’ value was spelled out in a pre-sale report on four farms, called the River Staation Partnership Properties, purchased by the Harrises. The parcels covered 8,875 hectares and were valued at A$9.5 million in 2008. But the report said more than half the parcels’ worth came from just 550 hectares, or 6% of the land, which had been laser-leveled for irrigation.

Under the new regulations, the extended Harris family got 12% of all licensed floodplain diversions in the Northern Basin. At two farms in the Barwon-Darling River Valley, Miralwyn and Geera—owned by Jane and Peter Harris’s business—the state allowed them to extract nearly three times more floodplain water each year than its initial yearly average estimates, according to confidential correspondence between the state government and the Harris’s business.

And because unused allocations can be carried over, the Harrises are now entitled to take 48.5 gigaliters of floodplain water in a single year at the farms after a four-year drought, to grow cotton, wheat, corn, sorghum and chickpeas. That’s nearly one quarter of the cap on water extractions for the entire valley. Now Jane and Peter Harris are suing the state’s water minister for an even greater annual allocation of floodplain water at the two properties, according to a Dec. 20 court filing.

In a statement, Jane and Peter Harris’s business said Miralwyn and Geera can together store more than 50 gigaliters of water.

Water Storage at Peter and Jane Harris’s Miralwyn and Geera

Miralwyn and Geera can store more than 50 gigaliters of water

The government’s licensing system is “a failure of public policy,” says Jason Alexandra of Australian National University’s Institute for Water Futures, who is a former senior executive at the Murray-Darling Basin Authority, the government agency that manages the river basin. Authorities, he says, aren’t abiding by their own sustainability principles. He believes the state should freeze floodplain licenses and launch an inquiry.

A spokesperson for the New South Wales water minister, Rose Jackson, said she was unable to comment on matters before the court, but noted that the government’s floodplain diversion models were “independently scrutinized and verified.” A New South Wales spokesperson wrote in an email that floodplain harvesting only occurs sporadically in wet years, and that licensing ensures the practice is sustainable.

Floodplain harvesting’s environmental destruction has left communities struggling. In the Macquarie Valley, cattle breeder Garry Hall surveys the devastation from the cotton diversions upriver. He is surrounded by hundreds of dead river red gums, an iconic Australian eucalyptus tree found on floodplains. They can live for centuries, but need periodic floods to thrive.

“Some of these blokes would have been hundreds of years old,” says Hall, examining the silver skeletons from under his gray felt hat.

For Indigenous Australians, the Darling’s decline is their third great dispossession since the British arrived 250 years ago—after the violent theft of their lands, and last century’s state-sanctioned kidnappings of Aboriginal children.

When the government gave out water entitlements to landowners a century ago, the land rights of Aboriginal people weren’t legally recognized. Today Indigenous Australians comprise 9% of the Basin population in New South Wales, but hold just 0.2% of water rights.

On a warm October day, the river near the town of Walgett has been reduced to stagnant green pools, a relic of the clear-running stream that a generation ago sustained an Aboriginal community of hundreds with mussels, perch, and cod. Even after three wet years, few dare to swim. The river water is too dirty to drink, and the town’s well water is too salty. Most residents, as a result, drink only bottled water.

“We just want our water back,” says Vanessa Hickey, 49, sitting with the Dharriwaa Elders Group under gum trees on the Namoi River.

The nation’s decision to channel scarce water supplies to industrialized almond and cotton farms, at the expense of traditional foodstuffs, has whittled away rural employment opportunities for Indigenous Australians, says David Doyle, an Aboriginal health practitioner with the Royal Flying Doctor Service.

He treats people in their 30s and 40s with addiction, heart disease, and what he calls “endemic grief” over the loss of Indigenous livelihoods. Average life expectancy among Aboriginal people is about eight years shorter than that of other Australians, and the gap widens to more than 12 years for those living in remote places.

In Wilcannia, another largely Aboriginal town down the Darling, the river frequently doesn’t flow at all, or worse, on hot days it oozes a sunbaked slime of poisonous blue-green algae. The algal bloom, composed of cyanobacteria, produces a neurotoxin called BMAA, which has been associated with the disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis by epidemiologists in the US. No such studies have been done in Australia, but one of every 200 Australian deaths is now attributed to ALS, up from one of 500 in 1986, says neurologist Dominic Rowe, an ALS researcher at Sydney’s Macquarie University.

Deaths attributed to ALS are rising even faster in parts of the Murray-Darling Basin, he says. “We suspect this has something to do with the water.”

In March, amid the throes of the dying Darling, 20 million to 30 million fish were killed near Menindee Lakes. The chief scientist of New South Wales, Hugh Durrant-Whyte, blamed Australia’s worst fish kill in living memory on suffocation from a huge flow of deoxygenated water, caused in part by “altered water use in the Northern Basin,” he wrote.

Growing up in Wilcannia, the Aboriginal leader Michael Kennedy, 41, ate fish every day from the Darling, which he and his friends caught by hand in shallow pools atop the town weir. That changed when the river’s flow plummeted around 20 years ago. Now he’s lucky to eat river fish twice a year. He hasn’t had the chance to teach his kids traditional fishing methods because the water rarely rises high enough.

“We were so much stronger and happier back then because the river was so much healthier,” says Kennedy, chair of the Wilcannia Local Aboriginal Land Council.

Down the Darling River, near its confluence with the Murray, PSP also owns one of the largest almond farms in the world, a 12,000-hectare mono-forest that’s one-third the size of the Canadian pension fund’s hometown, Montreal. PSP bought the farm, and 89 gigaliters of permanent water rights, in 2019 for A$490 million from a wholly-owned subsidiary of Singapore food conglomerate Olam Group Ltd., which PSP retained to manage it.

The deal was part of a splurge of big farming and water investments PSP made around that time in water-stressed regions, including the Australian cotton acquisitions, the 2018 purchase of a 17,000-hectare former sugarcane plantation on the Hawaiian island of Maui, and 6,900 hectares of mostly almond trees in California’s San Joaquin Valley in 2020.

The giant PSP farm is in a region called the Mallee, where sandy, salty soils dominate and land is relatively cheap. A cattle farmer from upriver, Lindsay Schultz, walks along the low-lying areas abutting PSP’s orchard where stunted trees struggle to survive in saltwater. This is where the Murray River ends up, flushed with underground brine, saturated in sands unfit for tree roots, and leaving behind groves of dead and dying almond trees. “These big corporations should bloody well come in here and clean up the mess,” says Schultz.

A spokesperson for Fresh Country Farms Australia, the PSP entity that owns the farm, wrote in an email that the trees were impacted by heavy rainfall in 2022 and that the company is working with authorities in the Mallee to improve the area’s ecological health. Fresh Country Farms Australia is monitoring the salinity issues and will consider planting replacement almond trees in more suitable parts of the orchard.

Simple water math says the almond mania can’t last. After recent plantings, permanent-crop demand for lower Murray water is set to rise by about 150 gigaliters in the next five years, with almonds responsible for more than 70% of that, according to the research firm Aither. That means in average rainfall years, the permanent crops will consume 80% of the river’s available irrigation, the firm estimates. In moderately dry years, their demand will exceed all of the lower Murray’s available water supply by 10%. And in extreme drought years, the lower Murray will have only enough water to meet about 40% of the permanent-crop demand, with nothing for anyone else.

Even Wheeler, the water-markets economist, thinks the nut may be hurtling toward a reckoning, particularly if states don’t impose land-use restrictions.

“We’ve got to deal with over-extraction,” she says.

Water is a prerequisite of prosperity. Without it, entire communities are at risk of being hollowed out as farms go under, jobs disappear, and economies wither. Nowhere is this clearer than in New South Wales’ Murray region, where the Campbells watched their dairy die of thirst.

Basic welfare in the region’s main towns plummeted over the course of Australia’s last two droughts. In 2018, the suicide rate among farmers nationwide, which generally rises during droughts, was nearly double the rate of non-farmers. Back in 2001, before this century’s two severe droughts, none of the three towns surveyed in Murray Irrigation’s service area ranked lower than the 45th percentile nationally in the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ index of socioeconomic metrics. Today, all three towns, plus two more added to the survey, rank in the bottom quartile. In that time, milk production at the region’s dairy cooperative, Murray Dairy, fell 46%.

In the Murray town of Wakool, a quarter of the local farms shut down in the past two decades and a fifth of the population moved away. Wakool’s supermarket is gone, the weekly nurse doesn’t come, and the once-rousing pub has gone sleepy. The school has nine students, down from 30 a decade ago. The town’s Australian football club, the social hub of rural Australian life, closed in 2018.

“You lose your footy club, it’s the end,” says Wakool farmer Matt Lolicato, 30.

While multiple factors drive socioeconomic decline, control over water is paramount. Independent water purveyors like Murray Irrigation were privatized in the 1990s, with shares distributed to their farm customers. Farmer-shareholders elect the directors, but the companies are run by professional managers.

Serving all sides of the water trade—buyers and sellers, farmers and financial firms—these irrigation companies control more than half the water in several parts of the Basin, as well as a “large proportion of trade,” according to the ACCC. Although technically non-profits, they buy and sell water with firms like Duxton, handling water as a source of income as well as the essential asset of their customers. And yet, the irrigation companies disclose minimal information about the deals they make with agribusinesses and financial firms, the ACCC found.

That’s why during the 2019 drought, farmers like the Campbells never had a clue that Murray Irrigation was sitting on enough water to sustain not only their own dairy, but many more farms like it.

It wasn’t until 2021 when an independent consultant discovered what was hiding behind the dam. Some local farmers, including one of Murray Irrigation’s own board members, hired Maryanne Slattery, a former manager at the Murray-Darling Basin Authority, to investigate why the water provider had been routinely late in delivering vital water to them.

One explanation stood out, Slattery realized. In 2019 and 2020, Murray Irrigation held between 150 gigaliters and 250 gigaliters of water in its so-called carryover account—water that users can save from one year to the next to hedge against supply disruptions. But Slattery found evidence that most of this water wasn’t carried over by ordinary farmers. It was held under Murray Irrigation’s own corporate account separate from farmers’ holdings.

This was important because the state allocates water to farmers based on the volume available excluding carryover commitments, water that’s technically already apportioned. More carryover means less available storage space, smaller water allocations, and higher market prices. This provides a mechanism for speculators to hoard water in dry spells to boost prices.

“Why did that water just sit there when people were desperate and spending a fortune on water and stock feed?” Slattery asks. “Was it because it was leased to financial investors who wanted it off the market during the drought? We may never know.”

Slattery and her consulting partner, Bill Johnson, met with Murray Irrigation’s management last year to find answers, but the company largely rebuffed their questions, they say. When they later reported Slattery’s findings to the Murray Irrigation board member who’d hired them, he asked the consultants to delete the carryover details in their report, they say. Company insiders were afraid they would be penalized for carrying over so much undistributed water, they told Slattery and Johnson.

Where the water went remains a mystery, shrouded by Australia’s lax regulation of water diversions. Ron McCalman, Murray Irrigation’s chief executive officer, says the holdback was a client matter and therefore confidential. “Individual customers make a decision to carry over water,” he says. “It’s not something we can control.”

Murray Irrigation provided Bloomberg Green a partial breakdown of its carryover amount in 2019 and 2020, but not how much was attributable to farmers and financial firms.

In the New South Wales parliament, legislator Cate Faehrmann of the Greens Party ordered emails and other documents retrieved from state water agencies that helped corroborate what Slattery discovered. In August, she gave a little-noticed speech in the state’s parliament calling out Murray Irrigation’s outsized carryover right up to the end of the drought in 2020, which she plans to investigate further in 2024.

“Somebody has to be held to account,” Faehrmann says. “New South Wales, particularly, was in absolute despair.”

In an email, a spokesperson for the state’s water agency wrote that “carryover is part of normal operations,” but did not respond to questions about Murray Irrigation’s carryover during the drought.

The best way to take in the Basin is above the fray in a plane, the privileged height of Chris Brooks. The Murray River cereals farmer spent a decade as CEO of Australian grain trading for Swiss-based Glencore Plc, one of the world’s largest commodities trader. Darting across the Murray-Darling in his twin-engine Aero Commander, Brooks has logged more than 10,000 cockpit hours since 1983. It’s how he knows why South Australians insist their Murray-fed lakes stay full, “so they can yacht around,” and how northern cotton growers “are effectively stealing my water.”

Brooks chairs the Southern Riverina Irrigators, a lobbying group representing 2,200 Murray region farmers. At the moment they’re waging an aggressive campaign to stop the federal government from buying back more water entitlements from farmers for environmental purposes. They’re also suing the Murray-Darling Basin Authority for alleged negligence in its management of the river by enabling water diversions to almond farmers and users downstream. The MDBA declined to comment as the legal proceedings are ongoing.

Brooks was furious when he learned from Slattery about Murray Irrigation’s massive carryover in the drought. A Murray Irrigation director himself until 2017, Brooks confronted its management about the matter, but they refused to discuss it, Brooks says. McCalman, the CEO, told Bloomberg Green that it doesn’t disclose certain decisions to its own directors because, as participants in the water market, they may have conflicts of interest.

Brooks is also leading opposition to Murray Irrigation’s plan to boost its water trading activity, which McCalman said is intended to raise funds for infrastructure projects.

“It’s fairly immoral that a company we own as shareholders is actually trading our water outside the system and impacting our production,” Brooks says.

From 10,000 feet, the contours of Australia’s water trading system come into sharp relief. The cotton growers hijacked the Darling on the northern floodplains, stanched the river’s long journey south into the Murray, which increased pressure on Murray farmers to cede their water to South Australia and the almond industry, Brooks says. Even for a Glencore man well-schooled in the doctrine of highest value, turning water into a commodity—one that has generated billions in wealth for traders and investors—has been a bitter pill.

“Water trading is the worst thing that’s ever happened,” he says.

Methodology

Water trade analysis

To examine the amount of water that is traded in Australia each year, Bloomberg analyzed temporary trades, which are one-time transfers of water, from the Bureau of Meteorology’s water data portal. Only surface water trades, which made up 96% of all trades, were analyzed; trades of water pumped from underground as well as zero dollar trades, which include environmental transactions and related-party water transfers, were excluded.

To measure the amount of water being traded and moved out of the lower part of the Murray Valley region, Bloomberg used trades identified in the data as "New South Wales Murray Regulated River Water Source / that part of the water source downstream of the River Murray at Picnic Point.”

In order to get an idea of the scale of water trading by one of Australia’s large water investors, Duxton Water, Bloomberg purchased Water Access License numbers for two of the company’s entities, called “Duxton Water Ltd.” and “Duxton Dried Fruits,” and obtained their temporary trading data from the New South Wales water register, which has information about water licenses, approvals and water trading.

Floodplain harvesting licenses

Bloomberg examined floodplain harvesting licenses issued by the state of New South Wales using data on its water register. New South Wales started issuing floodplain harvesting licenses in 2022 and has some of the most transparent water data in Australia.

To determine the total additional amount of water allotted under the new floodplain harvesting licenses, reporters compared state estimates of the historic levels to the amounts approved under the licensing program. The state used multiple models for measuring historic levels of floodplain harvesting. Bloomberg based its analysis on the “plan limit model,” following advice from experts. In doing so, reporters did not include estimates of water leftover from irrigation runoff that’s collected for reuse.

Reporters cross-referenced the Water Access License numbers from the floodplain harvesting data with records from the New South Wales Land registry data to get the names of the license holders. To determine the locations, Bloomberg used dam and levee construction approvals associated with the floodplain harvesting licenses.

Reporters also examined how New South Wales determined the amount of water specific landowners can take under the new licensing rules. To do this, Bloomberg compared confidential state estimates of the amount of floodplain harvesting at certain properties before the licensing requirements were put in place to the amount allowed under the new licenses issued.

Bloomberg found that two entities, the Canada’s Public Sector Pension Investment Board, or PSP, and the extended family of cotton growers Jane and Peter Harris, accounted for 26% of all the water allocated under New South Wales’ floodplain harvesting licenses. In compiling the amount of water allocated to PSP, reporters included licenses allocated to Bengerang, AFF Land Pty and Auscott; licenses allocated to Peter, Jane, Kenneth and Malcolm Harris, as well as licenses allocated to Merrywinebone Pty and Budvalt Pty were counted under the extended Harris Family. Though part of the same extended family, the Harrises manage different businesses.

To determine the number of floodplain harvesting licenses that went to institutional investors, Bloomberg counted floodplain harvesting licenses allocated to PSP, TIAA, IAI Australia and Macquarie agricultural funds.

No comments:

Post a Comment