Why China’s recovery is not what it seems

This is a guest post by Michael Pettis, a finance professor at Peking University and a senior fellow at the Carnegie-Tsinghua Center. His new book ‘Trade Wars are Class Wars’ was co-authored with former FT Alphavillain Matt Klein and is available at all good book stores.

On Tuesday, China’s National Bureau of Statistics released August data on the Chinese economy. It showed that while retail sales -- a proxy for domestic consumption (although it includes other things) -- was down 8.6 per cent for the first eight months of 2020, it nonetheless posted its first monthly year-on-year increase in 2020, with retail sales 0.5 per cent higher than last year.

The data also showed that industrial production was 5.6 per cent higher. Add to that a 4.16 per cent rise in fixed asset investment and a 19.3 per cent increase in August’s trade surplus, and the data left most analysts convinced that China’s recovery from the ravages of the Covid-19 pandemic was both solid and sustainable.

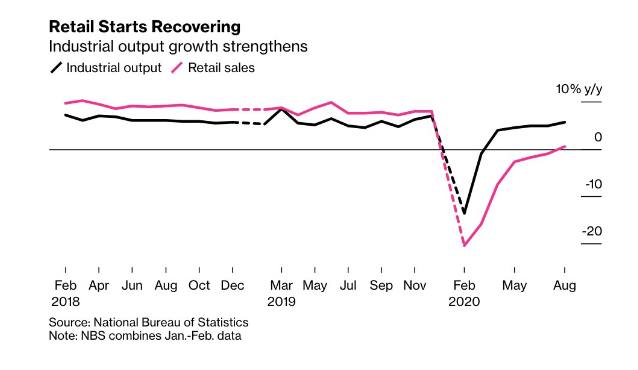

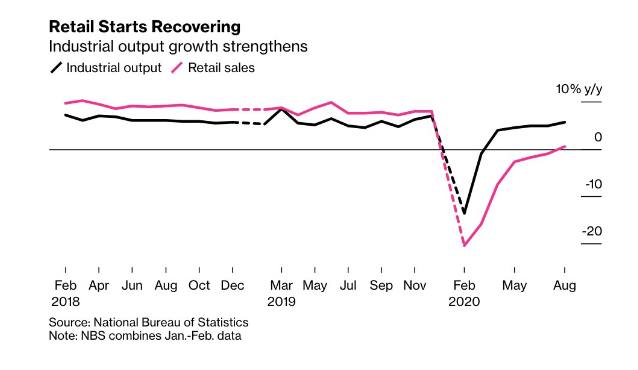

But this is not what the data suggest. In fact they indicate just how lop-sided and vulnerable China’s recovery has been so far. As the graph below shows, before 2020 retail sales had grown slightly faster than industrial production, indicating a slow rebalancing in an economy that urgently needed it. But in 2020 that relationship has inverted, with industrial production now growing so much faster than retail sales that it threatens to reverse the past two to three years of China’s limited rebalancing.

While industrial production for the first seven months of 2020 had been less than during the same period in 2019, the gap has been closing fast since June. The sharp increase in August’s production meant that for the first time in 2020, total production year-to-date had exceeded last year’s figure. If the production side of the economy were the constraint in China’s economic growth, as it was in the 1980s and 1990s, this would have been a clear sign it had recovered, and that is how most analysts are mistakenly reading it.

However, it’s been a long time since the production side of the Chinese economy has been the constraint. Even Beijing has publicly admitted for over a decade that the real constraint is the demand side: specifically domestic consumption, along with the private sector investment driven by said consumption. Since the turn of the century total Chinese production has so far exceeded the level it can sustainably manage. This has forced the economy into running huge trade surpluses and/ or extraordinarily high levels of public sector infrastructure spending to absorb the gap.

What the past few months of economic data tell us is that, not only has sustainable domestic demand barely recovered from the pandemic, but that even this limited recovery has been driven by Beijing’s substantial boosting of the production side of the economy. By expanding public sector investment in logistics and infrastructure, underwriting an expansion of credit to businesses, and otherwise subsidising production, Beijing has bolstered production to create the employment that has indirectly boosted consumption.

Put differently, economic recovery in China (and the world, more generally) requires a recovery in demand that pulls along with it a recovery in supply. But that isn’t what’s happening. Instead Beijing is pushing hard on the supply side, mainly because it must lower unemployment as quickly as possible. It is this push on the supply side that is pulling demand along with it.

The problem with this strategy is that it necessarily increases the gap between sustainable demand and total supply, as the graph clearly indicates. There are only two ways to resolve this. Either by a rapid increase in China’s trade surplus, which weakens the recovery abroad and forces an increase in foreign debt burdens, or by faster growth in Chinese public-sector investment, which, because most of it is no longer productive, increases the Chinese debt burden.

And this is exactly what we’ve been seeing in the data. Fixed asset investment is up, led by an even faster rise in public-sector investment, and China’s trade surplus is up sharply, now running at roughly 4-5 percent of GDP.

China’s “recovery”, in other words, is largely an exacerbation of the problems that have long been recognised by Beijing. It is a supply-side recovery in an economy that urgently needs more domestic demand but that has found it politically very hard to manage the wealth transfers that it requires.

This recovery isn’t sustainable without a substantial transformation of the economy, and unless Beijing moves quickly to redistribute domestic income, it will require either slower growth abroad or an eventual reversal of domestic growth once Chinese debt can no longer rise fast enough to hide the domestic demand problem.

No comments:

Post a Comment