Lula’s Nostalgia Trip Won’t Reinvent Brazil’s Future

Shrinking economic clout and a changed geopolitical landscape will dash the president’s hopes of reliving his past successes and restoring his country as a global player.

A geopolitical dead end?

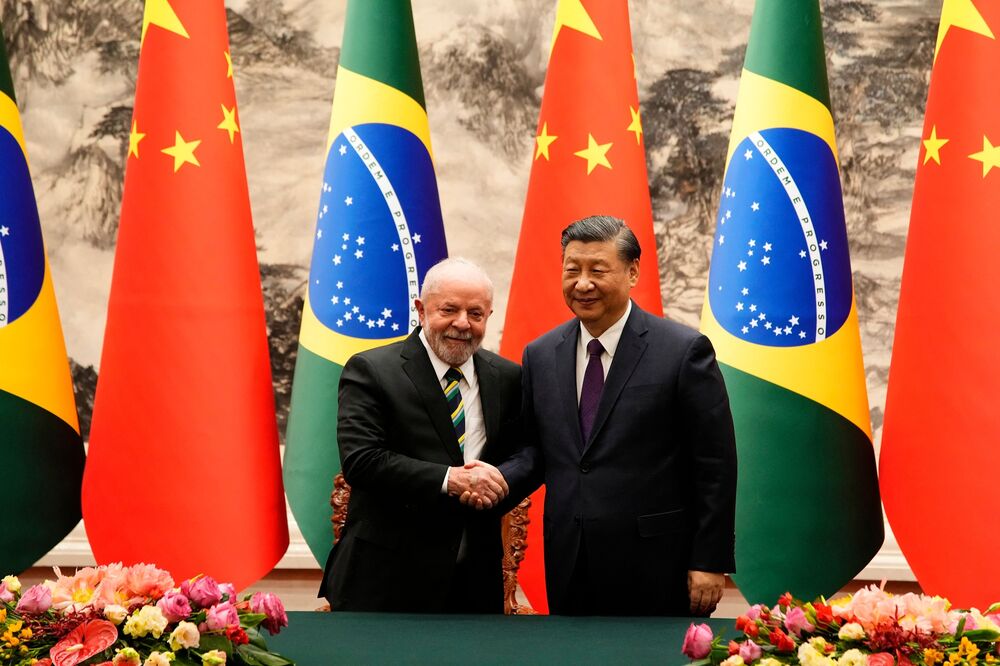

Photographer: Ken Ishii/AFP via Getty Images

Thomas Shannon, former US envoy to Brazil, believes the South American colossus once came very close to achieving something no other country has done, before or since: “becoming the first country to rise to great power status based on soft power alone.”

It was not just the sand and the samba. In the decade-plus after President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva came to power, Brazil became a commodities powerhouse, exporting oodles of iron ore, soy and beef. Oil production surged on the back of massive fields discovered off the coast of Rio de Janeiro.

In 2006 Brazil joined China, Russia and India to establish what would come to be known as the BRICS, which then accounted for over 11% of the world’s gross domestic product. Brazil hosted the World Cup of football in 2014 and the Olympics in 2016. A permanent seat on the UN Security Council, its diplomats thought, could not be far behind.

These heady memories are doubtless front and center in Lula’s mind as he continues his “Brazil Is Back” tour, which landed in China last Wednesday following trips to Egypt, Argentina and the US, on a visit that included high-level talks about both business and grand strategy with paramount leader Xi Jinping.

From a Brazilian perspective, the journey seems to make the utmost sense. China is Brazil’s biggest trading partner — buying more than three times as much Brazilian stuff as the US. And the Chinese seem itching to do more deals: 15 were signed during the visit. “This has nothing to do with ideology or geopolitics,” said Rubens Barbosa, former Brazilian ambassador to Washington. ”It has to do with Brazil’s economic interests.”

It also may help at home. Playing nice with the main market for Brazil’s agricultural exports (like playing nice with Russia, its main source of fertilizer) helps Lula’s standing among Brazil’s restive agribusiness barons, who hold down the right of the political spectrum and retain close ties to former president Jair Bolsonaro.

Broader ambitions seem to be at play, however. The BRICS (which added South Africa in 2010) now account for about a quarter of the world economy (or a third if measured by purchasing power parity). Their clout seems to offer a surefire shot at power: On Thursday Brazil’s newspaper O Globo reported Lula’s hope that China will support Brazil’s bid for that long coveted Security Council seat.

BRICS' Economic Footprint

Share of the world's GDP at market prices

Source: International Monetary Fund

And yet, Lula’s pronouncements in China have a musty smell of nostalgia about them. Lamenting the dollar’s hegemonic position; demanding a bigger role for developing countries in shaping global governance; extolling the BRICS bank as an alternative to an International Monetary Fund that “asphyxiates” developing countries: All that doesn’t ring as well in today’s world as it did back when Brazil was on the ascent and the West still welcomed China’s rise.

Moreover, Brazil’s gambit to assert preeminence on the global stage as a leader of the global south seems way past its sell-by date. Brazil is no longer what it was in 2016, when Lula’s handpicked successor, Dilma Rousseff, was impeached.

Since then, not only has Brazil’s clout in the world weakened, undermined at every turn during Bolsonaro’s authoritarian rule. Brazil’s economic footprint has shrunk too, to 2% of the world economy, from 3.3% when Lula left office in 2010. Since then, the Brazilian economy has been surpassed by Indonesia’s and vastly outpaced by India’s and China’s.

And though the BRICS’ aggregate economic clout has grown, it looks like a dodgy vehicle on which to hitch Brazil’s leadership ambition.

The idea of a BRICS bank with a preeminent role in global development finance, like that of a BRICS currency or a BRICS arbiter shaping rules for the global economy, seems far-fetched in a world where the R invaded its neighbor and the C is trying to manage a crumbling relationship not only with the US but also with much of the European Union, the world’s other economic powers. (Never mind the economic stagnation and corruption of the S.) “BRICS has lost its momentum,” Barbosa argued. “How can you negotiate with Russia in there? With the war it’s complicated to go ahead.”

For certain, Lula’s tip of the hat to Vladimir Putin, telling a French newspaper that Russia should be allowed to keep Crimea, didn’t sit well with Ukrainians and cast a dark shadow over Brazil’s declared interest in becoming a neutral mediator in the conflict.

Further east, China’s economy is not entirely on firm ground. It’s not only hungover from Covid’s lockdowns and threatened by a real estate implosion. The strategy on which it pinned its development over more than a quarter century is now threatened by US and European efforts to decouple their economies from China’s.

The Brazilian economy experienced a pretty hard landing after China’s demand for raw materials faltered in 2014. Given the new economic and geopolitical reality, one could look at Lula’s steps toward China and wonder, who benefits?

Monica de Bolle from the Peterson Institute for International Economics proposes that much of the Brazilian positioning is for show; at best an attempt to burnish some “Brazil brand.” For instance, the announced intention to circumvent the dollar in bilateral trade, she says, is just as ridiculous as the proposal for a new Mercosur currency. “That is all fluff,” she said.

She argues that it would make more sense for Brazil to focus on its relations with Europe and the United States, with which it shares market economics and a democratic system of government.

As Shannon notes, US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin’s visit to the conference of defense ministers of the Americas last year helped save Lula’s government by blunting the undemocratic temptations of members of Brazil’s armed forces who were close to Bolsonaro. Given the continued threats to democracy in Brazil and throughout the hemisphere, betting on Washington looks more valuable than cozying up to non-democratic regimes in Beijing, Moscow or an increasingly autocratic New Delhi.

To be sure, Lula came to the US first, before he went to China. And the Brazilian president did keep some distance from his hosts. Critically, he left Beijing without signing Brazil into China’s Belt and Road Initiative, disappointing Chinese who wanted to enlist Latin America’s economic powerhouse to join 21 of its neighbors in the project, including Argentina.

“It was the most important thing for China,” said Gaspard Estrada, who heads the Latin American Political Observatory at Sciences Po in Paris. “They wanted to pull Brazil into their garden.” As Lula left, the Chinese government had to content itself with offering to “actively explore greater synergy between its Belt and Road Initiative and Brazil’s reindustrialization strategy.”

Barbosa has a point when he observes that Lula’s emphasis is, to some extent, Washington’s fault. Brazil is eager to build closer ties with the US. But the US is too distracted with priorities elsewhere. The European Union, meanwhile, seems ready to ditch a hard-negotiated deal with Mercosur just to protect French farmers.

And one can build a plausible case for a non-aligned Brazil that stands on its own. “Brazil has the size to do partnerships with these big blocs and with other countries in bilateral accords,” said Finance Minister Fernando Haddad, who accompanied Lula to China. “It doesn’t make any sense that you are forced to make a choice that if you get close to one, you have to distance yourself from the other.”

Still, Lula needs to ponder the ultimate goals of his forays into foreign policy. What is the point of asserting Brazil’s global importance? What does it deliver? Is it in the right company to achieve that?

Shannon recalls some 20 years ago when Brazil nixed the development of a Free Trade Agreement of the Americas, pushing instead for deals with its neighbors, excluding the US. It failed, mostly. Mercosur never achieved much trade. And Brazil was encircled by US trade agreements with several Latin American countries, including Chile, Peru and Colombia. “They could have been leaders in the FTAA,” Shannon remarked. But they missed out.

Ironically perhaps, after China’s appetite for soy and iron provided Brazil with a new viable economic strategy, manufactured imports from China ultimately hollowed out Brazil’s industrial sector in much the same way that the country feared would happen if it had linked up with the US, Mexico and Canada in an FTAA.

It’s hard to know the future. It’s understandable, too, that Lula is swayed by his memories of a seemingly successful past.

And yet, before he chooses again to pursue a strategy built around BRICS to provide a counterweight to the G7, the IMF and the dollar, he should first carefully re-examine what he got from taking this path the first time around.

The way de Bolle puts it, “It didn’t amount to much.”

No comments:

Post a Comment